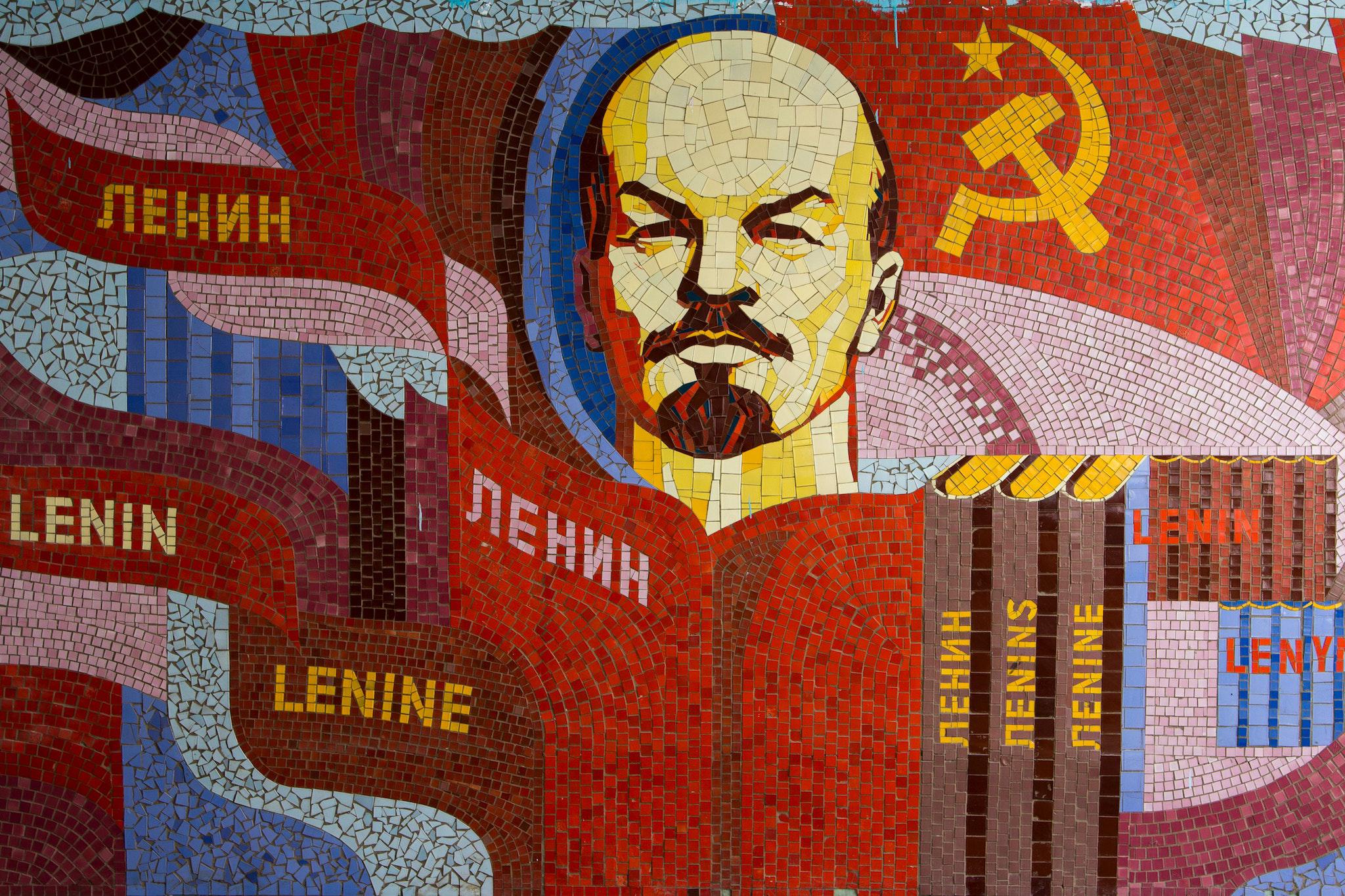

10 intellectuals who were expelled on Soviet Russia’s ‘philosopher’s ships’

Authoritarian regimes have had a long history of targeting intellectuals that don’t agree with them. It is a common thread among all authoritarian ideologies; communist, fascist, theocratic, and even democratic. While it often begins with attempts to discredit the intellectuals as unpatriotic or detached, it usually ends with execution or imprisonment.

There are a few notable exceptions to the typical pattern. In 1922, the Soviet government exiled 150 professors, theologians, philosophers, and writers on so-called philosopher’s ships in an attempt to remove dissidents. Revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky justified the action by explaining that, “We sent these people because they were not to be shot, but they were impossible to tolerate.”

Among these exiles were a slew of brilliant minds. Most of them were not active counter-revolutionaries, and none of them were active Bolsheviks. In many ways, it was an omen of darker things to come, as these thinkers lost their homeland for the crime of simple disagreement. Later dissidents would risk death.

Here are 10 of the most prominent passengers on the philosopher’s ships, why there were on them, and what they did after they got off.

Ivan Ilyin

A Russian political philosopher with a monarchist, and later fascist, bent, Ilyin wrote several books on politics, Russian society, and religion. He argued that social classes were necessary and that freedom consisted in knowing your place. He opposed republics for their divisiveness and tendency to ignore tradition. He later praised fascism, though he was opposed to the anti-Semitism and xenophobia of the Nazi regime.

After being sent to Germany by the Soviet government, he continued to work as an anti- Bolshevik intellectual. He was placed under surveillance by the Nazis and later fled to Switzerland. In 2009 his remains were returned to Russia with the help of Vladimir Putin, one of his biggest fans.

“Fascism does not give us a new idea, but only gives us new attempts to implement this Christian, Russian, national idea in our given conditions in accordance with our views,” wrote Ilyin.

Nikolay Lossky

A brilliant philosopher, Dr. Lossky worked in several fields including epistemology, metaphysics, and theology. His writings were so comprehensive that they are viewed as a system unto themselves, known as intuitive-personalism. He was a well-known and respected professor, and he was the only professor Ayn Rand could even remember having during her college years.

Despite being a moderate democratic socialist, Lossky was sent into exile by the Soviet authorities as they consolidated power. Living first in Czechoslovakia and then in New York, he continued to write and teach. He moved to France after the death of his son, the noted theologian Vladimir Lossky, and died there in 1965.

“Due to the tradition of the Church, Russia had an implicit philosophy, a philosophy that was born of the Neoplatonism of the Church Fathers. This implicit Neo-platonism is the true heritage of Russian thinking,” wrote Lossky.

Mikhail Osorgin

A writer, journalist, and essayist, Osorgin had a history of revolutionary activity before his deportation. He participated in the Russian Revolution of 1905 against the Tsar’s regime. He was arrested and deported but returned to Russia in 1916. He was then captured by the Soviets and deported for the final time in 1922.

He was the author of several books, including Quiet Street and My Sister’s Story. He worked for Russian émigré newspapers until his death in 1942. During his time in exile, he also co-founded a Masonic Order for Russian freemasons who were stuck in France.

The order to arrest and deport him read: ‘Osorgin Mikhail Andreevich. The right-wing cadet is undoubtedly an anti-Soviet trend. Employee of the “Russian Gazette.” Editor of the newspaper Prokukisha. His books are published in Latvia and Estonia.’

Nikolai Berdyaev

Born into the Russian aristocracy, Berdyaev was well educated and showed great intelligence even as a child. He had a youthful interest in Marxism, as was fashionable among the educated during the late 19th century, but later moved toward a proto-Christian existentialist philosophy which he wrote on extensively. He was a well-known academic when he was taken in for interrogation in 1922.

In The Gulag Archipelago, author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn tells us that Berdyaev was interrogated personally by the head of the secret police while he was imprisoned for his work by the Soviets. He was deported shortly after his release from prison and moved to Paris where he continued to write, teach, and lecture until his death in 1948.

“Berdyaev did not humiliate himself, he did not beg, he firmly professed the moral and religious principles by virtue of which he did not adhere to the party in power; and not only did they judge that there was no point in putting him on trial, but he was freed. Now there is a man who had a “point of view.” — Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago

Yuly Aykhenvald

Aykhenvald was a Russian author and art critic. He wrote several books and was noted for his unique approach to art, which incorporated Schopenhauer’s view of art as fundamentally irrational. He also criticized the style of most other Russian art critics as being thinly veiled political commentary.

He made the mistake of writing the essay Revolution: The Leaders and the Led, which attacked Leon Trotsky personally. This earned him a ticket on a philosopher’s ship to Germany. He continued to write for émigré publications until his death in a tram accident a few years later.

“There are no literary movements, only writers,” he wrote.

Sergei Bulgakov

A Russian Orthodox priest, the Reverend Bulgakov was also a Marxist in his youth before returning to the church after coming under the influence of Leo Tolstoy. He contributed to several books about religion, wrote articles for philosophical journals, and managed a publisher before the first world war. His works on theology were regarded as substantial even then.

In the years leading up to the revolution, he served as a member of the Russian parliament and became an ordained minister. During the civil war, he was a philosopher in the Crimea, where the Soviets found him and sentenced him to exile. As an émigré, he was a professor first in Prague then in Paris. He continued to write on theological matters until his death in 1944.

“Power in powerlessness, triumph in humiliation. And let our heart be our manger, in which we bear the divine sign, the sign of the cross.” — Sergei Bulgakov

Semyon Frank

A philosopher of Jewish ancestry, Frank converted to Christianity as an adult. While he was a firebrand Marxist as a college student—his activism once got him banned from the city of Moscow—he ultimately rejected Marxism for a general socialistic stance. A prodigious writer, he contributed regularly to philosophy journals and collections of essays. Amongst his earliest printed work, unfortunately for him, was a critique of Marx’s theory of value.

During the Russian Revolution, he was associated with Nikolai Berdyaev, which earned him a ticket out of the USSR. He was later forced to flee Germany as well. He continued to focus on philosophy in exile and covered many topics, including Marxism, free will, and religion.

“Socialism, in its main social and philosophical plan, is to replace the individual will completely with the will of the collective.” — Semyon Frank

Pitirim Sorokin

A brilliant sociologist, Sorokin founded the sociology department at the University of St. Petersburg. He made lasting contributions to social cycle theory and devoted a great deal of time to studying social mobility and hierarchies.

During the Russian Revolution, he served as a deputy in the Russian parliament before the collapse of the democratic government and communist takeover. He was an outspoken anti-communist who fought ardently against the Bolsheviks. He was arrested several times before his deportation.

He moved to the United States where he continued to teach and write. In 1940 he was invited to help establish the sociology department at Harvard University, where he worked until his death.

“[In-group exclusivism has] killed more human beings and destroyed more cities and villages than all the epidemics, hurricanes, storms, floods, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions taken together. It has brought upon mankind more suffering than any other catastrophe.” — Pitirim Sorokin

Fyodor Stepun

A Russian philosopher, Stepun was the editor for the Logos journal of philosophy. He served in the first world war and the Russian Revolution as an officer. After the Soviet victory, he worked for the state directing experimental theatre until his exile. He took up teaching and writing again in Dresden until the Nazis removed him from his post. He became a professor again after the war.

“In any event, we must remember that it’s not the blinded wrongdoers who are primarily responsible for the triumph of evil in the world, but the spiritually sighted servants of the good.” —Fyodor Stepun

Boris Brutskus

An economist with a Jewish background, Brutskus was a distinguished scholar and active Zionist who encouraged Jewish migration to the west of Russia. As a professor at the St. Petersburg Agricultural Institute, and later as the dean of the school, he wrote several books and articles on the economy of Russia, agriculture, and the Jewish people.

He was exiled to Berlin where he continued to teach. He later moved to Palestine where he died in 1938. Always an opponent of communism, he participated in anti-Bolshevik activities in Germany and authored the book, Economic Planning in Soviet Russia, critical of the new system.

“However, is a socialist society really able to pay the worker a full-fledged product of production without any deductions for the use of natural forces used in the process of labor, since they are given in limited quantities, and capital? Will not this order lead to absurdities and even … to injustices?” — Boris Brutskus