Should we be working less?

(photo by LEON NEAL/AFP/Getty Images)

- Is it time to rethink how we work?

- Research has shown that we both work more than is good for our health and more than is useful.

- Numerous companies and countries have implemented 35-, 30-, and even 25-hour workweeks.

It’s a little after lunch, and your struggling to keep your eyes open. Most of the important work in the day you finished in the morning. Sure, you could probably scrounge up something to do, but there are no pressing deadlines. Instead, you spend the second half of your workday switching between windows on your computer; maybe a spreadsheet for when your manager walks by, and maybe an article that’s grabbed your attention (like this one).

It’s more common than you think. The average worker spends a little under three hours a day doing actual work, and the rest of the time they chat with coworkers, look for a new job, check social media, read news websites, and a number of other things that aren’t really all that productive.

Turns out, we’ve been expecting something like this to happen for nearly a century. In the 1930s, the economist John Maynard Keynes predicted that his grandchildren would be working just 15 hours a week. Because of our advances in technology, we would be able to do in 15 hours what a 1930s employee could do in 40. Therefore, we’d have more time for leisure.

Sounds like he was on the money, right? The average worker really does only work about three hours a day, five days a week. Well, Keynes thought that we’d work a full day Monday and Tuesday, and the rest of the time we’d spend doing whatever we wanted. That didn’t happen. Instead, we’re trapped in offices, not exactly working, but not exactly relaxing either.

A Japanese office worker sleeps at a restaurant. Death from overwork in Japan is so common, they had to invent a word for it: karoshi.

(Photo by Jorge Gonzalez via Flickr)

Working ourselves to death

According to an analysis by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Americans — often described as excessively hard workers — spend about 1,780 hours working a year, or at least we spend that much time in the office. However, we’re dwarfed by South Koreans, who work 2,069 hours a year. South Koreans are in turn dwarfed by Mexicans, who work 2,225 hours a year. The Japanese are such hard workers they needed to invent a word for death from overworking: karoshi, which covers deaths due to heart failure, starvation, or suicide.

Clearly, something is wrong here. We aren’t all that more productive than Keynes thought we would be, but some of us are spending so much time at the desk that we’re literally keeling over and dying. Across the world, some companies and governments are trying something new.

A number of Swedish companies have cut back working hours in an effort to improve work-life balance.

(Photo by SVEN NACKSTRAND/AFP/Getty Images)

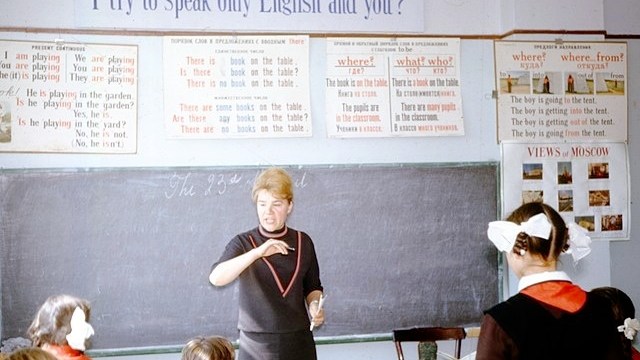

Experiments in taking it easy

Through March and April of 2018, a New Zealand company called Perpetual Guardian experimented with a 32-hour workweek. Employees worked Monday through Thursday but got paid as though they had worked the regular five-day workweek. Two researchers observed the experiment, and they found that workers reported, by 24 percent, more satisfied with their work-life balance without sacrificing productivity.

In Sweden, workers at a nursing home were switched to a six-hour workday schedule with no pay cut. An audit found that workers were more likely to show up for work, more productive, and healthier to boot.

Also in Sweden, a hospital switched to the six-hour workday schedule and, although costs increased, the hospital performed 20 percent more operations, waiting times were cut, doctors and nurses reported increased efficiency, and absenteeism dropped. Similar experiments being carried out in Sweden — or have been carried out — have all found that, at the very least, productivity remained the same.

Perhaps the most impressive example of this new paradigm is the entire country of Germany. Remember that Americans work about 1,780 hours a year? Germans work about 1,356 hours, among the lowest in the world. For a country famous for its efficiency, this is an incredible number. Keep in mind that Germany saved the Eurozone from collapsing in 2012 and has the fourth-highest GDP in the world as of 2017.

Sounds nice, but…

Of course, this model doesn’t always work out. France, for example, instituted a 35-hour work week in 2000. Since then, companies have complained that the law has made them uncompetitive, and France’s troublesome unemployment rate has remained static. Now, the law has so many loopholes that most French work more than the 35-hour maximum.

An American company, Treehouse, implemented a 32-hour workweek in 2015. Soon after, the company found it needed to layoff some employees — faced with firing its workers, the company reverted back to the 40-hour workweek. Plus, Treehouse is an online education company, and its customers wanted access to their service during standard business hours.

This ties into a larger issue: even if we’re only productive three hours a day, even if we aim to get much of the work done in the morning, sometimes it’s still difficult to know when those three hours of focused productivity are going to happen. Not to mention when they’ll be most of use. Indeed, in companies that deal with customers or that can face sudden emergencies, having employees in the office during regular hours might be non-negotiable.

But even if working less than 40 hours a week isn’t possible for many businesses, working more than that is clearly a bad idea. Doing so leads to cardiovascular issues and mental-health issues, and there are steeply diminishing returns in terms of productivity. Americans work about 8.8 hours a day on average — let’s not let it get to the point where we have to invent an English word for “death from overwork.”