Is It Better To Lose Yourself Or Be Redeemed?

If you feel that life is uncomplicated, easy, satisfying, carefree, under control – then this post is not for you. On the other hand, if you feel frustrated, anxious, deeply bored, or burdened by the sense that your life is meaningless – then this post may interest you.

In what follows, I will map a few options for how to proceed given this kind of existential turmoil. I will not be able to argue for any of these options in this short post, but I assume that sometimes even a sketchy map of a small part of the territory is helpful at a moment of acute disorientation. And a sketchy map is also helpful simply because it begs to be refined: the process of refining it, to which you are hereby invited, can be a process of re-orientation in and of itself.

I should note that I will not address here the matter of suffering that results from being denied what every person is entitled to by virtue of being a person (injustice). The following is more in the vein of ethical reflection suggested by Martin Buber when he wrote: “If all were well clothed and nourished, then the real ethical problem would become wholly visible for the first time.”

One response to existential turmoil is first to proclaim that it follows necessarily from an honest reckoning with the human condition, then to reject all palliatives in response and proceed instead to endure with angst. This kind of approach may rely on a family of values that include: the courage to refuse comfort, the pleasure of exposing other people’s illusions and forcing them to confront the darkness of their existence, the ideal of seeing the world truly, and so on.

I admit that I’ve rigged my description of this approach so that it seems somewhat problematic on its face. With its own virtues to take pride in (courage), pleasures (raining on other people’s parades), and ideals (perceiving the stark truth of the world as it really is), this view, in spite of itself, is hardly lacking in palliatives.

The disingenuousness, even fraudulence, of professing such a view makes it very unappealing to me. Nevertheless, there are certainly better and fairer ways to present such a view and some of you will find it worth looking for them. As Montaigne once wrote, “There is some shadow of daintiness and luxury that smiles on us and flatters us in the very lap of melancholy. Are there not some natures that feed on it?”

There are two general approaches that I suspect will have broader appeal, which I will describe as: losing yourself and striving for redemption. It will become clear that these are not particularly clean analytical distinctions, nor do they exhaust the array of options available. But they will do fine for the purposes of this brief post.

The “losing yourself” approach assumes that existential turmoil is produced to a significant degree by the processes through which you differentiate yourself as an individual. These processes range from the mere use of language – saying “I” – to asserting ownership, having and seeking to satisfy desires that can only be satisfied by your own consumption, pursuing individual achievement, and so forth.

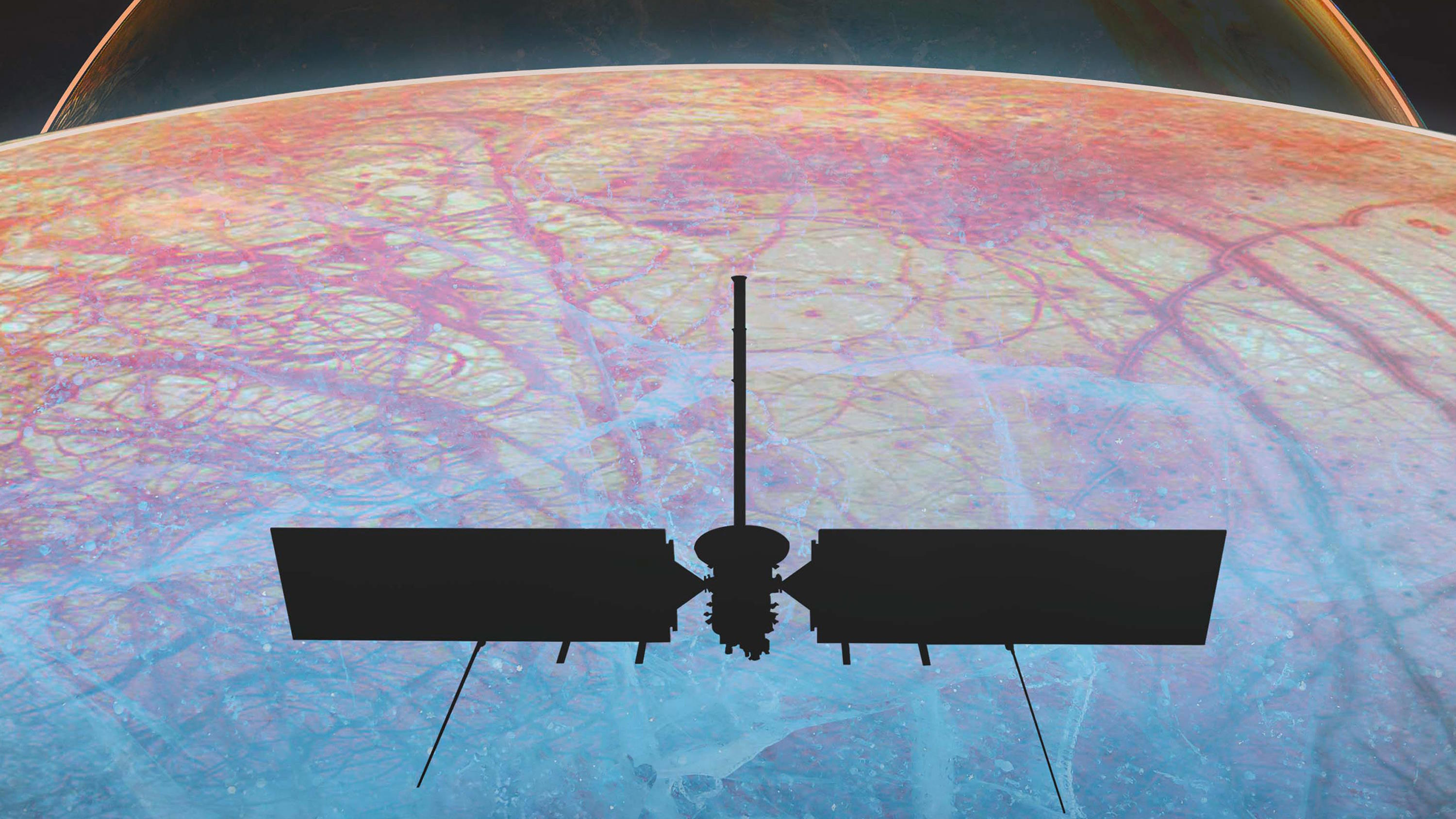

There are a variety of ways to set about losing yourself. Some people try to relinquish their autonomy and individuality by submitting themselves to a higher authority (joining a monastic order or the military, for instance). Alternatively, you might try to “open yourself” to the grandly external: to allow yourself to be awed by nature’s enormities (the Grand Canyon, the ocean, etc.), hoping to be overwhelmed, humbled, or diluted into nothingness.

There is, inversely, the path of isolation: to separate yourself from others, from thoughts about others, indeed from everything that is external or attaches to the external. The hope in following this path is to quiet yourself into existential silence.

The “striving for redemption” approach, by contrast, posits your existence as a promissory note to be made good, redeemed, through effort. Ways to seek redemption include: focusing on the precise and steadfast fulfillment of your moral duty, building your character on the model of an ideally virtuous and admirable person, expressing your individuality, pursing a life-project [see my previous post: “Do You Deserve To Have A Job That You Love?”], and striving to triumph over others in some competitive context. Of course, all of these can be related.

Just to hint at the numerous problems with the basic distinction that I have drawn: following moral rules in order to be redeemed may actually involve losing yourself in the fungible status of the “moral rule-follower;” isolating yourself from the vicissitudes of life with others may veer from a silencing of the self into a kind of self-indulgence. Anway, the point here is to stimulate the needed process of refinement.

There are a few decidedly mixed approaches that I want to highlight. The path of self-criticism, for instance, posits as redemptive courageously telling truth to oneself about oneself; this approach asserts the self only in order to break-up and undermine the self in an infinite process of the serpent eating its tale.

Since I mentioned Buber earlier: there is the mixed path of dialogue, in which the goal is simultaneously both to present one’s self fully and open oneself fully to the “externality,” so to speak, of another person.

My own primary bulwark against existential turmoil is mixed: losing myself in the contemplation of ideas and cultural artifacts, only to be invigorated by the presumptively redemptive self-assertion involved in the act of interpretation. Another mixed approach, secondary in my arsenal, is to lose myself in contingently established rituals that I creatively and idiosyncratically shape over time [see my previous post: “Pizza Night and the Politics of Purity”].

How do you decide what is the right criterion to use when choosing from among these options? That will require further thought. On the other hand, we might simply revive that old existentialist motto: just leap!