Nearly 3,000 shipping containers have fallen into the ocean since November

Credit: Andreas via Adobe Stock

- At any given time, 6,000 containerships are moving the vast majority of global trade on the world’s oceans.

- The average number of annual containership accidents has been on a downtrend for the past decade, but accidents have become more common since the start of the pandemic.

- One factor behind the recent rise in containership accidents could be rising demand for imported goods from U.S. consumers.

In November 2020, the containership ONE Apus was sailing from China to California when a severe storm struck. The 364-meter ship began rolling heavily. Soon, nearly 1,800 of the ship’s containers—some of which were carrying dangerous goods like fireworks and liquid ethanol—came loose. Some crashed onto the deck. Others spilled into the ocean, lost forever.

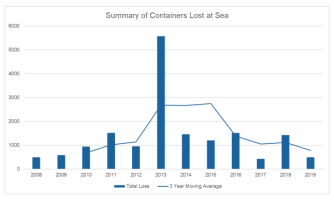

The ONE Apus incident was one of at least six major containership accidents that occurred since November, which altogether have resulted in the loss of 2,980 containers. That’s more than double the annual average number of lost containers from 2008 to 2019, according to a recent report from the World Shipping Council.

What’s causing the uptick? It’s likely a combination of bad weather and heavily loaded ships, some of which are packed to the brim due to increased U.S. imports since the beginning of the pandemic. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that January brought the largest monthly increase in U.S. imports since 2012.

To be sure, the World Shipping Council notes that containership accidents have been on a downtrend over the past decade, writing “containers lost overboard represent less than one thousandth of 1% of the roughly 226 million containers currently shipped each year.”

ONE Apus Arrives in Kobe, Japan Revealing Cargo Lossyoutu.be

But that fraction of a percent adds up over time. After all, international containerships move more than 80 percent of global trade, representing a roughly $4 trillion industry. And while accidents are relatively rare, they pose significant threats to crew and the environment, not to mention the economic costs.

In its recent report, the World Shipping Council notes several ways the industry has been working to improve safety standards, including increased inspection programs and updated packing practices.

Still, accidents are bound to happen among the 6,000 containerships that are sailing the world’s oceans at any given time. One reason is parametric rolling, a phenomenon only experienced by containerships.

The World Shipping Council

In short, parametric rolling is a sudden side-to-side movement of a large ship caused by a specific alignment of waves, usually during a storm. Parametric rolling can send containers, which are sometimes stacked six stories tall, toppling over each other.

Bigger ships tend to be more at risk.

“The new container ships coming to the market have large bow flare and wide beam to decrease the frictional resistance which is generated when the ship fore end passes through the water, making it streamlined with the hull,” wrote Marine Insight.

“As the wave crest travels along the hull, it results in flare immersion in the wave crest and the bow comes down. The stability varies as a result of pitching and rolling of the ship. The combination of buoyancy and wave excitation forces push the ship to the other side.”

Credit: Pixabay

On a broader scale, the cost of shipping goods by any method—train, truck, air, ocean—is rising as supply chains are becoming congested and demand for imports keeps increasing. For the most part, companies are fronting the bill.

As for U.S. consumers? They might start paying a premium for imported goods, or for goods that feature imported parts.

“Most prices along the supply chain have gone in one direction, and that’s up, so it has to appear somewhere,” Joanna Konings, a senior economist at ING, told CNN Business.