The Medea effect: When a parent harms their child to get back at someone else

- The Medea effect refers to the phenomenon in which a parent harms their child as a way to seek revenge.

- It can manifest through physical abuse as well as relationship manipulation, such as fabricating false narratives, undermining the other parent, and restricting communication.

- The result can often be deep-rooted harm and lifelong trauma for the child.

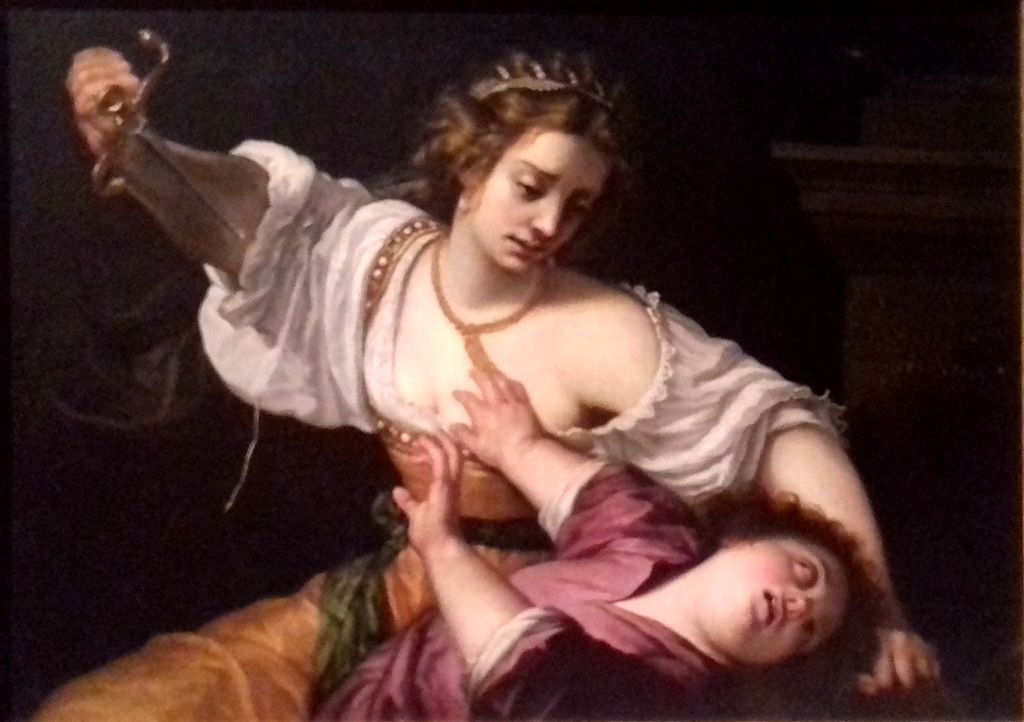

Jason was a man in need of a fleece, but not just any boutique fleece. This being ancient Greece, and Jason being an Argonautic hero with divine blood coursing his princely veins, he was searching for the golden fleece. And after years of questing, battling, and rowing, he arrived in Colchis to claim his gilded prize.

There were the usual kinds of challenges, such as plowing a field with fire-breathing oxen, and Jason handled them all heroically. One challenge, though, proved too much. He couldn’t get past a scaly and sleepless dragon. Lucky, then, that he fell in love with a princess and sorceress named Medea. Medea gave Jason a magic potion to drug the insomniac leviathan, and the two hot-footed it away with his shiny new cardigan to live happily ever after.

Except not quite. When the young couple found themselves in Corinth as poor and insignificant civilians, the honeymoon ended. Jason got itchy feet and decided it was far more glorious and worthy of a hero to marry a princess. He abandoned Medea and their two young children. Medea was spurned, proud, and furious. She wanted desperately to hurt Jason for the pain he caused her. But how? Jason was courting a princess in a guarded castle, sipping wine and eating grapes. So, Medea did something monstrous. In a mad-hot rage over the betrayal, she killed her own children. She loved her children, but retribution mattered more.

In those last few lines, the story comes down to Earth. The millennia melt away, and we have here the all-too-familiar story of a family broken by betrayal, pride, and spite. This is known in psychotherapy as the Medea effect.

The Medea effect

There are two ways to view the Medea effect. The first is when we encounter those devastating stories of a mother killing her children because they got in the way of her other life plans. They occasionally pop up on the news, and they elicit a surge of anger and indignation. Susan Smith, for instance, drowned her two children in a car because she was obsessed with a man who didn’t want kids.

Carl Jung theorized that the reason we find these stories so much more disturbing than other cases of infanticide is that they invert the “Mother” archetype. For Jung, a mother is supposed to be the embodiment of care and love. They are the rock for any child; however, when a mother abandons that role — by neglect or murder — we rage about the cruelty and the “Terrible Mother” inversion.

While stories of maternal infanticide are heartbreaking, the more common version of the Medea effect is when a mother harms a child to “get back” at an old partner or spouse. A typical way this is done is when a mother fights tooth and nail in court to deprive a father of any form of custody. In cases where the father is a caring parent, the act harms the child to hurt the father. This version of the Medea effect is known as “parental alienation syndrome.”

Learning to hate dad

In the 1980s, child psychologist Richard Gardner coined the term “parental alienation” to refer to an indoctrination strategy in which one parent portrays the other as evil. Over time, the child’s relationship with the other parent frays, and they learn to avoid, shun, or even hate them. In the case of the Medea effect, the mother vilifies the father, but parental alienation more broadly can go either way.

Here are three examples of such strategies:

False narratives. In some cases, one parent will fabricate stories or exaggerate situations to paint the other in a negative light. This could involve unproven, unsubstantiated accusations of neglect, abuse, or other harmful behaviors.

Undermining. A parent might belittle or criticize everything the other one does in front of their children, hoping the children learn to disrespect them. For instance, a father might undermine the character of a mother with lines like, “Oh, mommy wouldn’t be able to do that” or “You can’t expect any better from your mom.”

Restricted communication. In a household setting, one parent might insist on taking on certain emotionally important roles. A mother might claim “only she” can nurse a sick child. A father might refuse a mother the right to take the child to some sports events. In a divorced context, one parent can limit the phone time a child has with the other. They might say a child can “only” meet a parent in a certain setting, for a certain time, and with specific supervision.

Long-lasting harm

All of which can cause deep-rooted harm and lifelong trauma for the child. The psychiatrist Robert M. Gordon wrote a paper called “The Medea Complex and the parental alienation syndrome” about his experiences witnessing divorce proceedings as a court-appointed child custody evaluator. He noted: “It is not only cruel to the alienated parent, but it produces life-long harm to the child. It is psychological child abuse … Such brainwashing and alienation usually lead to a lifelong problem with establishing and maintaining healthy intimacy.”

Gordon’s paper is full of case studies about such lifelong harm. Today, parental alienation is well documented and has proven harmful to children.

For Gardner, parental alienation tactics are born of Medea-type powerlessness. As he put it in the 1980s: “Because these mothers are separated and cannot retaliate directly at their husbands, they wreak vengeance by attempting to deprive their former spouses of their most treasured possessions, the children.” And both Gardener and Gordon assumed parental alienation tactics to be the main reserve of mothers. Gordon argued, “I believe that brainwashing by a mother is more powerful than that of a father, since the child’s bond with the mother is usually more primitive.”

Even if we disagree with those gender roles and Jungian archetypes, we can appreciate the huge damage parental alienation can have on children. As is often the case in psychotherapy, when we have a name for something, we can better inoculate against it. Knowing some parents can and do harm their children, let us call it out.