Scientists have discovered where anxiety comes from

Anxiety disorders are common and may be growing more so. 40 million US adults suffer from one in some form, about 18% of the population. Worldwide, 260 million live with an anxiety disorder, according to the WHO. Economist Seth Stephens-Davidowitz reported in 2016 that anxiety disorders have doubled in the US since 2008. There are a number of different kinds. There’s general anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety, and of course, a near countless number of phobias.

Although common, physicians aren’t sure what exactly brings on such a disorder. They usually hit a person in the prime of their life, and the treatments we have now are generally, only partially effective. Medical researchers hypothesize that it’s a combination of genes, environmental conditions, and changes inside the brain that lead to such a disorder.

Anxiety often runs in families and epigenetic markers for it have been identified. Epigenetics is the system by which genes are marked to become either expressed or suppressed. A recent study found that epigenetic changes associated with anxiety that occurred in holocaust victims, were passed down to their children.

Although we know that damaged circuits inside the brain are related to anxiety disorders, we haven’t had a clue which ones, until now. Neuroscientists have announced they’ve identified the brain cells associated with anxiety in mice. This was a collaboration of researchers from UC-San Francisco and Columbia University’s Irving Medical Center. Mazen Kheirbek, Ph.D., was the senior investigator. He’s an assistant professor of psychiatry at UCSF. He and his colleagues results were published in the journal Neuron.

Researchers at UCSF and Columbia University identified “anxiety cells” in the brains of mice. Credit: Pixababy.

These “anxiety cells” are where the emotion is stored. Kheirbek and colleagues started their search with the hippocampus, a part of the brain known to be associated with anxiety. It’s also involved in emotion and memory. Researchers placed miniaturized microscopes in the brains of mice and then put the rodents in stressful situations.

Mice are afraid of wide open spaces, where they can easily be spotted and scooped up by a predator. So the scientists took these newly equipped mice and placed them inside mazes where some of the corridors terminate in an open space. Kheirbek told NPR, “What we found is that these cells became more active whenever the animal went into an area that elicits anxiety.” The reason researchers call them “anxiety cells” is, these special neurons only fire when the animal confronts a situation that’s scary.

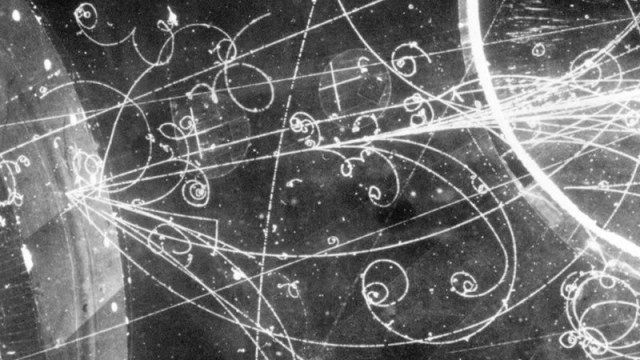

Although this showed that such cells are involved with anxiety, it didn’t prove that the feeling originated with them. To prove that, Kheirbek and colleagues employed a technique called optogenetics, where neural activity is controlled using beams of light. When they turned up activity in the aforementioned brain cells, the animal became more anxious, but when they turned down activity, it became less so.

Optogenetics is a system that introduces genetic material containing opsin into neurons for protein expression, and applying light emitting instruments to activate it. Credit: Pama E.A. Claudia, Colzato Lorenza, Hommel Bernhard, Wikimedia Commons.

Even though it’s the origin, the emotion doesn’t start and stop with anxiety neurons. “These cells are probably just one part of an extended circuit by which the animal learns about anxiety-related information,” Kheirbek said.

Connections to the smell circuit and memory circuits for instance, might remind a mouse that a certain smell in the past, say cat urine, lead to a dangerous situation, like almost getting eaten. So these cells in the hippocampus may be where anxiety emanates from, but many other brain circuits’ work in concert with it, to help the mouse navigate the environment.

The hope is to develop better anxiety medications. “The therapies we have now have significant drawbacks,” Kheirbek told NPR. “This is another target that we can try to move the field forward for finding new therapies.”

Imagine a specialized drug that can snap anxiety off like a switch? The limitation of this study is that, such cells were identified in mice and not in humans. Still, researchers are pretty sure we have them, too. And future studies will likely corroborate these findings.

To learn more about optogenetics, click here: