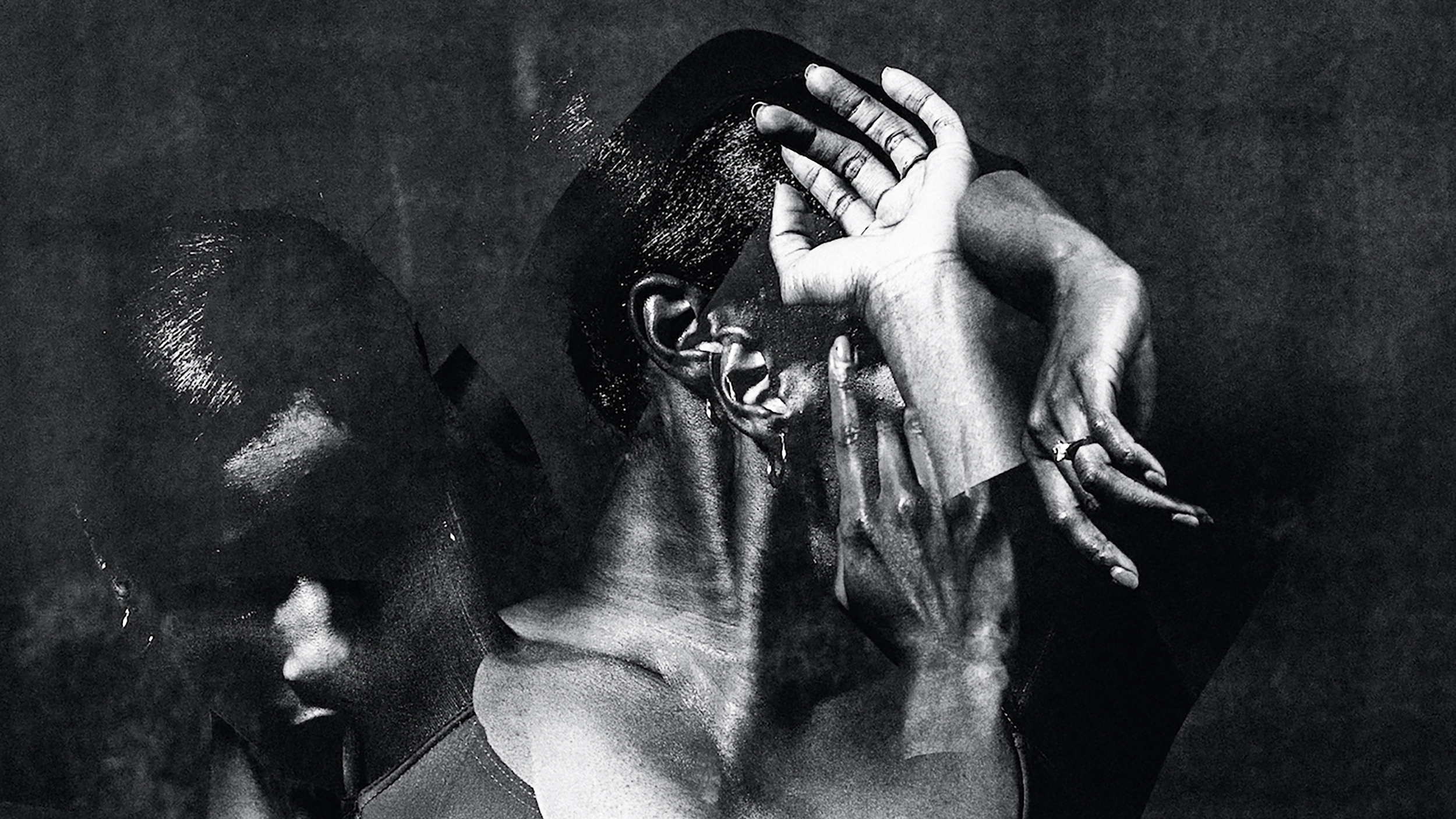

How psychedelics could help silence chronic pain

- Researchers are exploring how psychedelics might help the brain “snap out” of chronic pain, a condition that’s sometimes disconnected from any physical injury.

- Chronic pain can be deeply psychosomatic, reflecting the complex relationship between the mind and body, making it challenging to treat.

- Preliminary evidence suggests that psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin can beneficially disrupt the brain’s pain pathways, especially when used alongside more conventional therapies.

What if symptoms of chronic pain were sometimes just echoes of a past injury, and your brain could “snap out of it” with the help of psychedelics? It’s a surprising theory that several labs around the world are beginning to investigate. While there have been few double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of psychedelics for treating chronic pain, preliminary evidence is beginning to emerge — with promising results.

The source of chronic pain

Chronic pain is defined as pain that persists beyond the usual recovery period or occurs with another condition. It may occur continuously or happen off and on. The most common manifestations of chronic pain are lower back pain, headache disorders, fibromyalgia, and neuropathic pain. People treated for chronic pain often undergo “pain management programs” that combine approaches from different fields to customize treatments.

Although it may be a reflection of ongoing physical health issues, chronic pain can also have deeply psychosomatic origins, reflecting the close relationship between mind and body.

“Neuropathic pain can lead to a centralized pain syndrome where the pain is still being processed in the brain,” says neuroanesthesiologist and neuroscientist Joseph Cichon, assistant professor in the Perelman School of Medicine at UPenn, in an article for UPenn’s website. “It’s as if there’s a loop that keeps playing over and over again, and this chronic form is completely divorced from that initial injury.”

This is one reason chronic pain can be notoriously difficult to treat.

Patrick Finan, Harold Carron Professor of Anesthesiology at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, told University of Virginia Today that the central nervous system may become “sensitized,” such that neurons continue firing pain signals long after the initial injury.

“In the case of chronic lower back pain, an MRI can show clear pathology in the spine,” he said. “Other times, and really quite often, patients will report they are experiencing real chronic lower back pain that’s not viewable by techniques like MRI. It’s not to diminish the pain people are reporting or to suggest they’re making it up. The resolution of our techniques does not always align with the reality of people’s pain.”

So how can we break the cycle?

Chronic pain and psychedelics

Psychedelics show promise in treating chronic pain in ways that resemble their power to treat depression and other mental illnesses: They shake up the brain’s well-trodden neural pathways.

Cichon, whose team studies ketamine and psilocybin for chronic pain, says this is why psychedelics could be a promising tool. “Maybe this is sort of the sledgehammer or tool that the brain needs to be shaken up so it can land back down into a normal state.”

So far, LSD and psilocybin have shown potential therapeutic value in treating cancer-related pain, phantom limb pain, cluster headaches, and migraines. The idea of treating pain with psychedelics is nothing new. According to Kooijman and Willegers, who published a 2023 review on the topic, a Japanese study from 1967 noted “a significant and sustained reduction in phantom limb sensation in seven out of eight patients [treated with LSD], as well as pain relief in five of six patients.”

However, more recently there has been an uptick in research, especially within innovative studies combining psychedelic therapy with other established treatments. For instance, in 2018 Ramachandran et al. highlighted the chronic pain relief that can come from combining psilocybin with mirror visual-feedback (MVF), where a subject’s intact limb is placed next to a mirror so that the visual input of its reflection overrides the sensory loop of the phantom pain from the missing limb. This treatment was found to be more effective than psilocybin therapy alone, resulting in pain relief that persisted for several weeks. It’s thought that the activation of the 5-HT2A receptor “might make the brain more receptive to MVF by enhancing communication between the visual and somatosensory cortex,” Kooijiman and Willegers write, leading to long-lasting pain relief.

Psychedelics as a treatment for cluster headaches gained ground in the early 2000s when a cluster headache patient started an online forum (clusterbuster.org) and shared his story of using LSD to achieve complete remission of his pain. A flurry of studies on self-medicating subjects followed, showing either acute abortion or complete remission of cluster attacks. Sub-hallucinogenic doses were also reported to be effective. In 2023, an open-label interventional study kicked off in Denmark to investigate the pain-alleviating effects of psilocybin in cluster headaches. Two additional randomized control trials will investigate the safety and efficacy of psilocybin and LSD as treatments.

The exact mechanisms remain unclear, but researchers think serotonergic processes (with possible anti-inflammatory effects), dopaminergic processes, neuroplasticity, or changes in brain functional connectivity (e.g., changes to the default mode network) could be involved. On a more granular level, evidence suggests that psychedelics can inhibit the anterior insular cortices in the brain.

“When pain becomes chronic, a shift from the posterior to the anterior insular cortex reflects the transition from nociceptive to emotional responses associated with pain,” write Kooijiman and Willegers. “Inhibiting this emotional response may alter the pain perception in these patients.”

Although the serotonin hypothesis is the most popular theory of those listed above, the full story may not be quite as reductionist. In a piece published in Scientific American, Boris Heifets, a Stanford Medicine anesthesiologist who studies pain, called the serotonin theory a “red herring.” Instead, he urged researchers to focus more on mind-body interaction. There is a link between the mood-improving effects of psilocybin and the neurological connections between depression and physical pain, he says: “If these drugs are going to help, it’s going to be much like the way we think they help for depression—[that is], changing your relationship to your pain.”

In that sense, a big part of chronic pain relief may be mind over matter.

The path forward

Psychedelic treatment for chronic pain is being tested in labs across the world, including one of the labs that ushered in the psychedelic renaissance: Imperial College London.

“Chronic pain conditions like fibromyalgia cause untold suffering to individuals and those close to them,” James Close, a pain specialist, physiotherapist, and PhD student at Imperial College London whose own work explores the treatment potential of psychedelics for chronic pain, told Big Think. “Every week I see patients in my pain clinic whose lives have been completely destroyed by this all-consuming condition. Unfortunately, there is very little we can offer them to help beyond therapy around how to manage their pain, and medications such as tricyclic antidepressants which only work occasionally and are poorly tolerated.”

Close and his team at Imperial College London are currently collecting data for one of the first controlled studies on psychedelics for chronic pain in a clinical population.

“There is a desperate need for alternative treatments for these people and I think psychedelic therapy may provide an answer,” Close told Big Think. “Maybe not always as a cure for their condition, but as an offering of hope to what must feel like a bleak future. Nonetheless, before we can get these medicines to those that may benefit from them, we need to first show that they help under controlled conditions.”

Before that, he says, there is even more work to do around destigmatizing chronic primary pain conditions (pain that cannot be explained by any other diagnosis) so that patients can “find the holistic support needed to find a way forward in life.”