Does the body really “keep the score” of trauma?

- Bessel van der Kolk's 2014 book The Body Keeps the Score argued that trauma affects both the mind and body.

- This perspective challenged the traditional idea that trauma is solely a mental phenomenon.

- There remain many open questions about the extent to which the body versus the brain holds and processes trauma, emphasizing the intricate connection between physical and psychological well-being.

Trauma is not merely a phenomenon of the mind but also a condition physically embedded in the body, often eluding our conscious awareness and affecting our overall health. That was the main argument in psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk’s 2014 bestseller The Body Keeps the Score, which quickly became a modern classic among trauma researchers, clinicians, and survivors. The book shifted how many in the West view psychiatric illness, which was often viewed solely through a psychological or neurochemical lens, and it sparked new interest in more holistic treatments for trauma that had long been considered alternative: yoga, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy (EMDR), the performing arts, and psychedelics, to name a few.

But what does it really mean for the body to “keep the score”? Is it biologically possible for the viscera to actually store and release trauma? In his book, van der Kolk writes:

“The body keeps the score. If the memory of trauma is encoded in the viscera, in heartbreaking and gut-wrenching emotions, in autoimmune disorders and skeletal/muscular problems, and if mind/brain/visceral communication is the royal road to emotion regulation, this demands a radical shift in our therapeutic assumptions.”

Can the body “keep score”?

Recently, neuroscientists have expressed skepticism over the notion that the body can “keep score” of anything. In a 2023 Big Think video, Lisa Feldman Barrett argued that everything, including trauma, is in our heads, and that “the brain keeps the score and the body is the scorecard.” In her view, everything we experience is constructed by the brain, which learns to predict how we will feel based on past experiences, issues, and sensations that seem to come from our body but actually come from our brain.

“When you feel your heart beating, you are not feeling it in your chest, you are feeling it in your brain,” she said. “Your body is always sending sensory signals to the brain, of course, but emotions are made in the brain, not in the body. They are experienced in the brain, like everything else you experience, not in the body. If you experience a trauma, you experience it in your brain.”

Bottom-up treatments like yoga, massage, and breathwork would then serve to override predictions and provide the brain with a different experience of the body.

“It’s not your body that needs to heal,” she said. “It’s your brain’s predictions that need to change. It’s not biologically possible for the body to keep score of anything.”

The line between scorekeeper and scorecard, however, may not be so clear. While the conscious experience of trauma may be constrained to the brain, there is a mountain of evidence that trauma impacts the physiological systems of the body, which can set off a cascade of bodily processes that in turn impact the brain.

“It’s entirely likely that the viscera ‘record’ stress and carry a lingering memory of such,” Paul Kenny, PhD, an addiction researcher and professor of neuroscience at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, told Big Think.

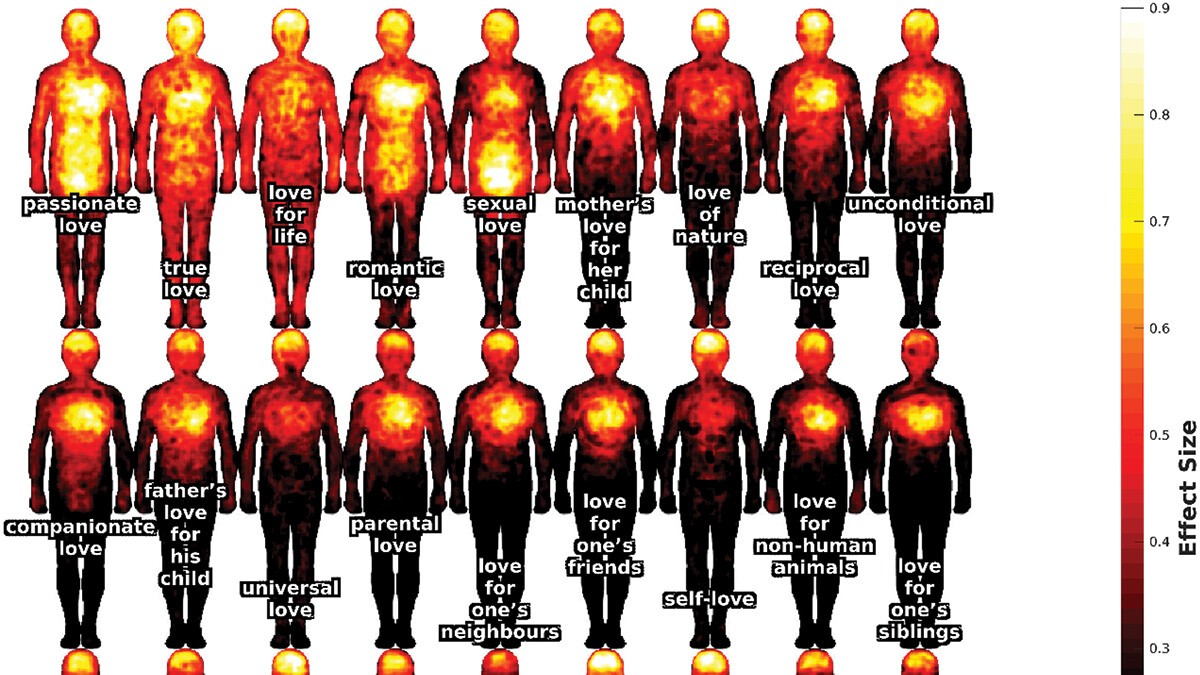

“For example, the immune system, which interacts with both sensory and autonomic neurons, is highly stress-responsive. Also, stress profoundly modifies the function of peripheral organs (e.g. release of glucoregulatory hormones from pancreas; liver storage and release of glucose). Adipocytes are also stress-responsive, and stress remodels the way that fat is stored in the body. So, indeed, the viscera are likely highly sensitive to both acute and chronic stressors.”

These processes may rely on interactions with the brain, but if some of them originate in peripheral systems, can we really say the body isn’t keeping score? If trauma can result in chronic inflammation or autoimmune disease, one might argue that the expression of these conditions itself is no less valid than the brain’s construction of an emotionally triggering experience. The question then becomes semantic: “Keeping the score” doesn’t have to mean being conscious of keeping the score. Lymphocytes, white blood cells that promote adaptive immunity, “keep score” of every antigen they’ve encountered, forming memory cells in the immune system. The heart and enteric system can function independently of the brain, keeping their own score of metabolic processes. More often than not, what happens inside us is a two-way partnership between the brain and viscera, but it’s not always clear who’s in charge.

Who’s in charge?

When it comes to treatment, physical therapists and bodyworkers who work with trauma patients are well-acquainted with this partnership. Scroll any bodyworker’s website and you’ll read testimonies and descriptions of how “emotional energy” gets stuck in the body. No one actually knows how deep tissue massage leads to emotional catharsis, but the fact that it can seems to align with van der Kolk’s claims, as well as those of medical celebrities like Gabor Mate, author of When the Body Says No.

There’s growing evidence that such treatments have a direct effect on the brain. Cynthia Price, a research professor at the University of Washington who runs Seattle’s Center for Mindful Body Awareness, has found in her own work that body-oriented interventions such as Mindful Awareness in Body Oriented Therapy (MABT) can change the plasticity of the brain in areas related to self-awareness.

“It is quite possible that there are physiological changes in the body related to interoception,” she told Big Think. (Interoception is the sense that allows an individual to perceive the internal state of their body.) “We certainly notice shifts in bodily tissue/musculature in response to MABT processes of sustained interoceptive attention.”

How emotional energy might be “stored” in the body — for instance, in patterns of tension that contribute to the way the brain represents the body, and therefore the self — is an open question. In framing trauma as blockages in the viscera, are we oversimplifying bidirectional processes that are valuable to understand on a deeper level? And in relegating the body to a scorecard, are we defining intelligence too narrowly? These are urgent questions as we reconceptualize wellness, healing, and mental health according to the complex connections between the brain and body.