Want students to cheat less? Science says treat them justly

Credit: Roman Pelesh/Shutterstock

- Students in German and Turkish universities who believed the world is just cheated less than their pessimistic peers.

- The tendency to think the world is just is related to the occurence of experiences of justice.

- The findings may prove useful in helping students adjust to college life.

Some people believe that the world is a just place where people tend to get what they deserve. The merits of this belief have been subject to debate for a few centuries, and some argue that its bad for you. It is a popular belief in any case and some social psychologists argue that it is a fundamental belief that allows us to function.

But how does this belief, which must surely be challenged every day, affect our lives? A new study published in Social Justice Research suggests that a personal belief in a just world may help us act justly, after finding that it reduces instances of cheating in college classes.

The study is the most recent addition to a long line of work focusing on the belief in justice, our behavior, and our reactions to evidence that might suggest injustice occasionally occurs. This study focuses on a personal belief in a just world, (PBJW) rather than a general belief in a just world (GBJW). The difference between them must be highlighted.

GBJW is the stance that justice prevails all over the world and that people tend to get what they deserve. PBJW is more focused on the individual’s social environment and their belief that they tend to be treated justly. While several studies show PBJW correlates with a higher sense of well-being and a variety of other positive effects, a high GBJW is associated with less life satisfaction, negative behavior, and callousness towards the suffering of others. This study controlled for GBJW, and focused on PBJW as much as possible.

To assure that culture was not a factor, the study included students at universities in both Germany and Turkey.

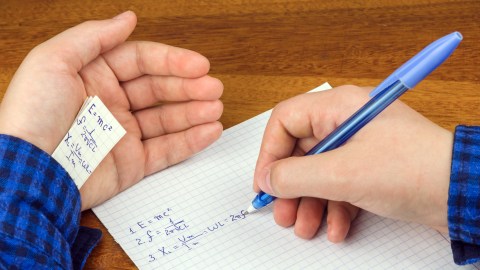

The researchers gave students at the four participating universities a series of questionnaires that asked if they ever cheated in class, if they perceived the world to be just, if they though that justice always prevailed everywhere, their tendencies towards socially appropriate behavior, their life satisfaction, and if they felt like they were treated justly by their teachers and fellow students.

The answers were statistically analyzed for relationships. While some of the connections seem trivially true, others were surprising.

PBJW turned out to only be an indirect predictor of if a student was likely to cheat. Both a belief in a just world and a lower likelihood of cheating were mediated by the justice experiences of the students, with more of these positive experiences lowering the rate of cheating and improving their belief in justice. This was also associated with higher levels of life satisfaction.

These effects existed across all demographics in both countries.

In a way, it seems to be. People who have reason to think the world is just to them tend to interpret events in a way to sustain that belief and behave in a just manner. In a larger sense, the take away from this study is that experiences of justice, both from peers and instructors, is vital to student’s wellbeing and understanding that the rules that exist about cheating are part of a larger, legitimate, system.

The researchers, citing previous studies on the perception of justice, note that “justice experiences (1) signal that university students are esteemed members of their social group, which in turn conveys feelings of belonging and social inclusion and (2) motivate them to accept and observe university rules and norms. These cognitive processes may thus strengthen their well-being and decrease the likelihood that they cheat.”

The authors also suggest that if you want people (not only students) to act justly; consider treating them with “civility, respect, and dignity.”

Sometimes, all it can take to help somebody act virtuously is to treat them well. Likewise, people treated harshly can rarely find reason to play by rules that don’t protect them. The findings of this study will certainly add to the literature on how we perceive justice in the world around us, but might also help us remember that there are real consequences to our actions which can be much larger than we imagine.