Holocaust survivor on freeing yourself from the prison of your mind

- At 16 years old, Edith Eva Eger was imprisoned at the Auschwitz concentration camp, but she survived and immigrated to the US.

- Today, Eger is a psychologist who has helped many people overcome trauma through the realization that it’s not what happened to you; it’s what you do with it.

- In an interview with Big Think, Eger also discusses her path to healing and how acts of kindness reveal our shared humanity.

“Is she your mother or your sister?” A seemingly innocent question, perhaps even a flattering one under the right circumstances. Such circumstances, though, would not be found in Auschwitz.

Josef Mengele asked Edith Eva Eger this question when she first arrived at the concentration camp in 1944. An SS officer and physician, Mengele would go on to earn himself the nickname “the Angel of Death” for the atrocities he performed under the Reich’s auspice. Eger had yet to learn of his monstrous reputation or the horrors of Auschwitz. She also didn’t realize that only one answer would protect her mother. She only knew that she was a scared, confused 16-year-old girl.

“Mother,” she answered truthfully.

Her mother was directed to a line of Jewish women on Mengele’s left. Eger and her sister, Magda, to the one on his right. Neither would see their mother again.

Auschwitz took the lives of an estimated 1.1 million people, among them Eger’s mother, father, and her young beau, Eric. She and Magda endured the hellish conditions for months before being led on death marches to other camps by Nazi forces desperate to evade the encroaching US and Russian forces. They were rescued by US troops at Gunskirchen a year after their imprisonment. There, Eger had been left for dead among the bodies of other victims — emaciated, back broken, and body wasted by pleurisy, pneumonia, and typhoid fever.

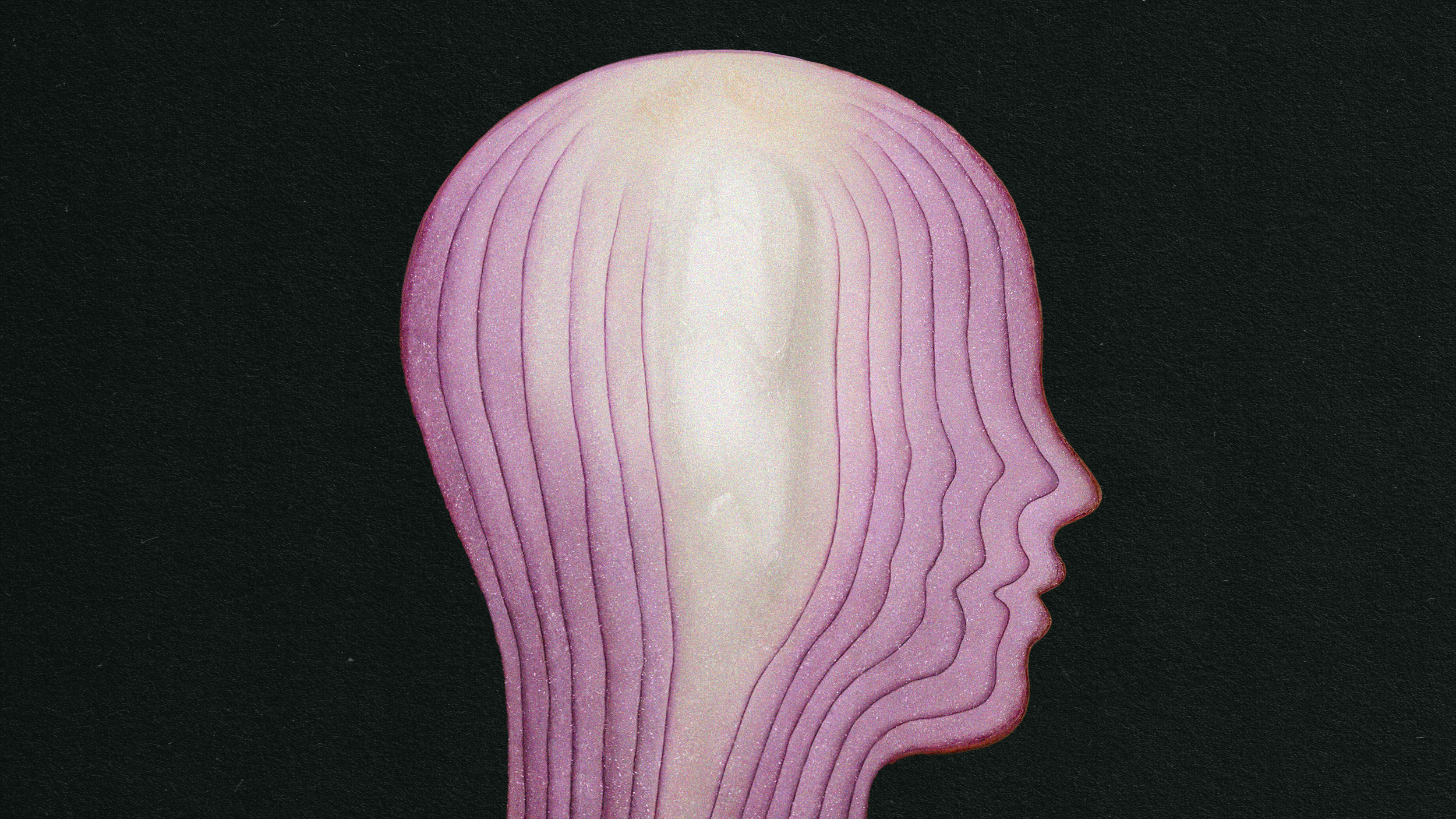

Eger survived and was nursed back to health, but while her body recovered, it would take decades before she would escape the prison of guilt and denial she had built inside her mind.

The prison of the mind

Today, Eger is 97 years old. She enjoys life in sunny La Jolla, California, and during our interview, she wears vibrant oranges and yellows to match the natural beauty surrounding her. In her early fifties, she earned her PhD in psychology, specializing in post-traumatic stress. She has also raised a family and written two books on her experiences during the Holocaust, The Choice (2017) and The Ballerina of Auschwitz (2024).

She is as far from the horrors of Auschwitz as it is possible to travel in a lifetime, but the road to La Jolla was long and far from straightforward. “It was close to 20 years until I finally admitted to people that my classroom was Auschwitz,” Eger tells Big Think.

After the Holocaust, neither Eger nor her sister talked about that grueling year. They chose instead to suppress the pain and ignore the memories, but despite their efforts, the experiences nonetheless managed to bleed out to the conscious surface. When confronted with images from the Holocaust, Eger would become physically ill, and even seemingly innocuous and everyday sights or sounds could trigger crippling flashbacks.

In The Choice, Eger describes a time when she was riding the bus to her factory job after immigrating to the US. She boarded, sat, and waited for a ticket collector to come by, as was customary in her European homeland. When the bus driver confronted her, yelling to either buy a ticket or get off, she fell to the ground shaking with fear.

After moving to El Paso with her husband, Béla, Eger began studying psychology at the University of Texas. The career choice led her not only to help others reconcile with their crushing pasts but also to recognize the need to confront her own.

“I have talked to many, many survivors who were able to function well and be able to have families, and they don’t live in the past. You remember the past, and you can even do many things that you learned [with it]. But you’re not there,” Eger says.

Her studies and conversations led her to a crucial lesson on trauma’s influence over the mind: It’s not what happens to you; it’s what you do with it. It’s a lesson Eger has passed on through her clinical practices, in her books, and to her family.

To be clear: That’s not to disregard the Holocaust’s many atrocities. Eger experienced that barbarous inhumanity first-hand. She watched as some captives, broken and disconsolate, chose to walk into the electrified fences surrounding the camps. Others lost themselves to despair.

In a heartbreaking story recounted by Eger, a fellow prisoner named Anna convinced herself that they would be liberated by Christmas 1944. “All Christmas Day, she pauses to listen,” Eger writes in The Ballerina of Auschwitz, “to lift her eyes to the farthest line of fence, breath fogging the air around her head, a smile on her chapped lips. But our liberators don’t come. The next morning, Anna is dead.”

This part of the Holocaust story is significant, and it would be an injustice to the ill-treated innocents to forget it. What’s often missing from this story though, Eger’s grandson, Jordan Engle, pointed out during our interview, is what happened after 1945 — the stories of the people who chose not to let this suffering define them but to use it, learn from it, and pursue their life’s meaning in spite of it.

Eger personifies this aspect of the Holocaust: “I am free. It’s a lot of effort to be free from the prison that is in your mind, and the key is in your pocket.”

The key in your pocket

While the shape of any one person’s key will be unique, Eger believes a vital notch is learning to accept your authentic self. For her, that meant recognizing that she was victimized at Auschwitz, but she was not a victim. Those experiences would be an indelible part of her life, but they didn’t define her identity or life story. Rather than pretend they didn’t happen or let them control her thoughts, she would choose how to think about and live with those experiences. For her, that meant using them to help others and better understand the best and worst of what it meant to be human.

“I want people to know that no one can replace them,” Eger says. “Maybe [someone else] looks like you. Maybe they talk like you, but there is just one of you here.”

Another notch in the key is an adherence to kindness. While Eger’s memoirs don’t shy away from the immorality of the Holocaust, they also shed light on the numerous small acts of grace and mercy that helped people endure. Eger sharing a loaf of bread she had tucked away with others. A kind word that raised another’s spirit for a moment. A guard who looked the other way when a prisoner broke the rules.

Such acts not only helped many survive, but they showed Eger the shared humanity that bound everyone who experienced Auschwitz together, a recognition that ultimately led her to forgive her tormentors. As she expresses in her writings, she realizes that the Nazis themselves had been brainwashed. Their rigid thinking and identities made them prisoners of their minds too, and that prison ultimately destroyed them.

“I shook my fist at God before I got to this [point]. And I’m still not done,” Eger says. “I’m still in the process of hopefully being free from my own prison, which is in my mind, and the key is in my pocket. I know it’s there. I just have to reach for it.”

Only you can choose to be free

In 1990, Eger returned to Auschwitz. When asked why, she says simply, “To experience it one more time and wonder, “How did I survive?’”

When she went, the wrought-iron words Arbeit macht frei (“Work sets you free”) still hung over the entrance to “the world’s biggest cemetery.” The first of many false promises meant to keep Auschwitz’s prisoners complaisant in the face of their looming deaths. But the lie that haunted Eger on her return was the one told to her by Mengele: “You’ll see your mother very soon.”

For decades, Eger wondered if she had condemned her mother. She had chastised herself for her naivete and questioned how it might have been different if she had simply lied. But the important choice, she came to realize, was not the one made when she was “hungry and terrified […] surrounded by dogs and guns and uncertainty.”

Instead, she writes, the choice that matters is the one she makes now. The choice to accept herself; the choice to be imperfect and even so be happy; the choice to stop questioning why she survived and commit herself to the truly freeing work of serving others and making the world a better place.

“I didn’t run away from the past,” Eger says. “I did a lot. I’m still doing a lot. As long as I live, I’m going to work. I don’t believe in any kind of retirement.”