“You need resilience”: How a genocide scholar faces history’s darkest moments

- The stereotype of the melancholic academic — popular in world literature — is not accurate.

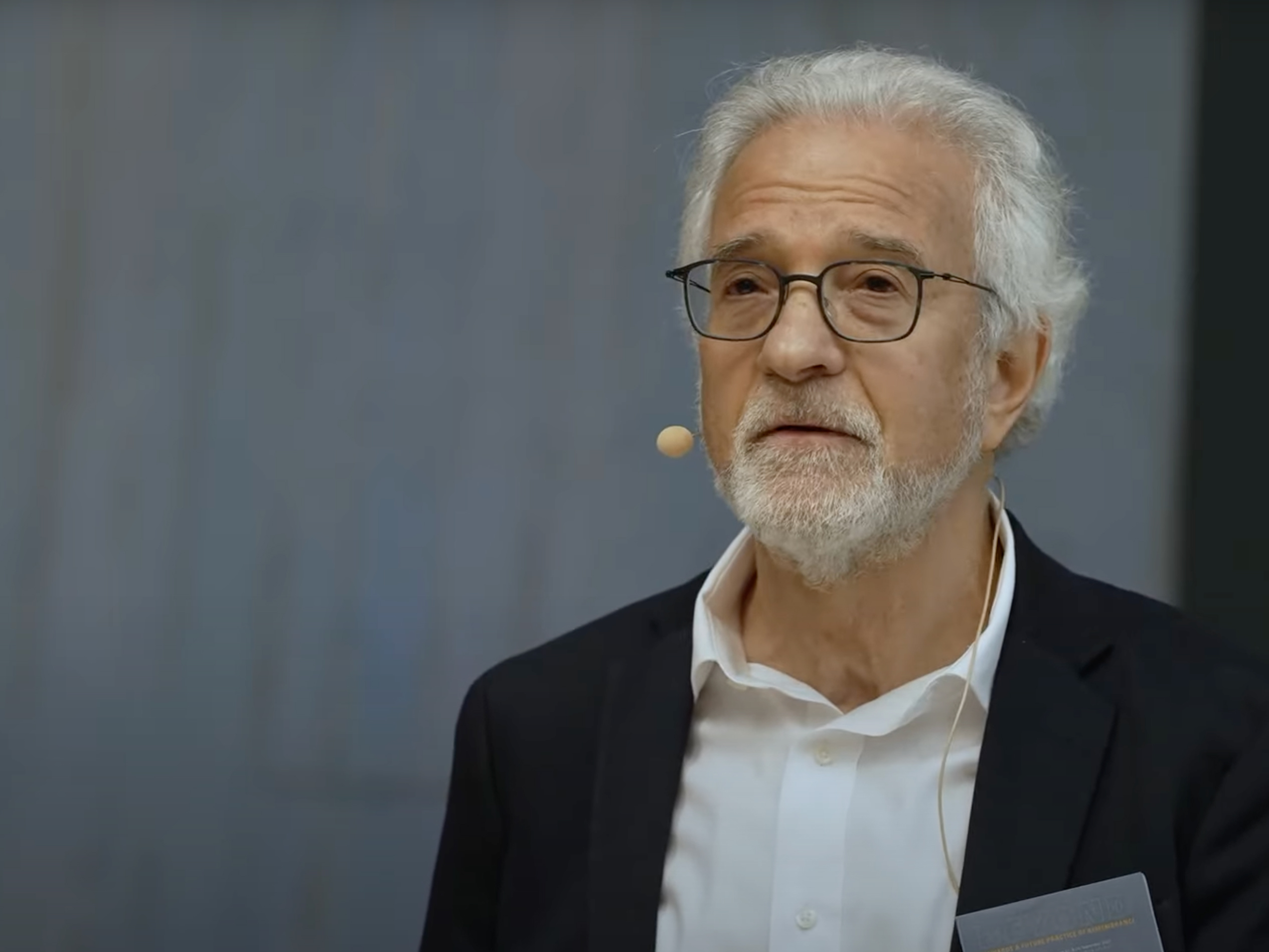

- Genocide historian Omer Bartov says studying his particularly challenging subject has made him more mentally resilient.

- In this interview, he reflects on the link between mental health and academic study.

From the Greek myth of Prometheus to Goethe’s Faust, world literature has no shortage of stories about people whose hunger for knowledge ultimately causes them pain. The popularity of these stories has contributed to the stereotype of the moody intellectual: cynical, pessimistic, depressed. Think of the philosopher who, through logic and reason, concludes that “God is dead,” or the cosmologist who, peering through their telescope, attempts in vain to fathom the unfathomable size of the Universe.

This stereotype, while rich in narrative potential, is just that: a stereotype. In truth, studies show that the higher someone’s level of education, the better they can navigate the challenges of mental illness. Researchers mostly observe a negative correlation between melancholy and intellect, not a positive one, and many leading thinkers view their knowledge as a blessing rather than a curse.

“I actually find adopting a cosmological viewpoint to be kind of…comforting?” Matthew Bothwell, an astronomer at the University of Cambridge, told Big Think. “There’s something about appreciating the smallness and insignificance of my little human life that I find quite relaxing. No matter how much politics gets me down, or life’s stresses build up, we’re all just temporary collections of atoms, and the Milky Way will keep on spinning long after our brief candle has gone out. It puts our problems in perspective.”

Even scholars who study subjects as difficult and distressing as the Holocaust do not succumb to sorrow, though this doesn’t mean they are made of stone. “There have been moments where I needed to take a break,” says Omer Bartov, an Israeli historian who since 2000 has served as the Samuel Pisar Professor of Holocaust and Genocide at Brown University.

When Bartov moved from German military history to Holocaust studies, he focused on first-hand accounts from survivors. Not only because these were valuable and deserved attention, but also because there was “a tendency in Western writing about the Holocaust to use figures, or talk about how it was planned and executed. There was, not a repulsion, but a discomfort with examining its effect on individual human beings.” Most challenging were accounts written by people who, during the Holocaust, had been of the same age as his daughter. “You begin to imagine your own child in that kind of situation.”

Equally distressing are moments when Bartov anticipates seeing history repeat itself. “Certainly the world we live in today seems to have forgotten whatever lessons it drew from the vast explosion of violence that occurred in World War II and after, which is a very depressing observation,” he told Big Think. Bartov added that this predicament is not unique to him but shared by historians who specialize in other themes and periods. “In general, people have forgotten the relatively recent past, and repeat the same cycles of populist, authoritarian regimes.”

Corpses in your head

While Bartov’s personal coping strategies are not the same as the ones you’d find in your typical self-help book, that doesn’t make them any less effective. “I guess I belong to a generation that is less concerned with that kind of terminology,” he said, referring to contemporary buzzwords like “mental well-being.”

“When you study war, you can think about it in two ways. One: This is so hard for me. Why am I doing this when I could engage in something more cheerful? The other is: How can I feel bad when what I’m reading and writing about is so much worse? Instead of feeling bad about myself, I am reminded that the people I study were undergoing far greater traumas than I ever had to face. It is a kind of privilege. Added to that is the fact that is important to tell these stories since many people do shy away from telling them because they are so distressing.”

To an extent, guidelines of scientific inquiry protect him from psychological damage, with historians being expected to establish a so-called “critical distance” between themselves and the subjects they investigate. Allow yourself to become too involved, or too emotionally attached to your research, and you run the risk of compromising the integrity of said research.

“You can retain distance mentally,” Bartov noted, “but also physically, by dividing your day so you are not constantly immersed in your work. You have to make sure you do other things, at least so you do not go to bed every night with a bunch of corpses in your head.”

Other things can be many things — music, films, walks — whatever allows you to take your mind to a different, less threatening place. Bartov’s preferred thing is fiction writing, specifically historical fiction. His latest book, The Butterfly and the Axe, is set during the Holocaust, just like his academic research. Still, when operating in the realm of fiction, Bartov can exercise a degree of control that he does not have in his day job: “I have actually found that to be the big difference, between understanding the chaos that genocide victims feel and cannot or rarely manage to overcome, and your role as a writer, who is putting things in order.”

Bartov’s method of coping with negative emotions reflects that of the Holocaust survivors he has worked with. “People who have confronted horror personally, not just vicariously, have told me they don’t indulge in that,” he said. “They are not terribly interested in delving into the traumas they have encountered and how they became part of them.”

If they did confront their past, they did so as writers — memoirists, scientists, or scholars. It’s an approach that, as mentioned, creates a sense of separation while also allowing people to turn chaos into order and make sense of senselessness.

Mental health and academia

The relationship between mental health and academic research, long overlooked, is finally receiving more attention on college campuses. Still, there is an ongoing debate about how the issue should be addressed.

“As a university professor, I know there is much worry about the well-being of students, safe spaces, and not using terminology that might trouble young people,” Bartov said. “But what I deal with is troubling. And when I teach it, I tell my students it is deeply troubling and that they might not want to take this class. If you do want to know about these issues, you need some resilience.”

His attitudes toward mental health may differ from those of his students and fellow administrators, but they have thus far proven effective. At least, for him.

“I guess I sometimes get a bit impatient with the expectation of mental fragility,” he said. “Not actual mental difficulties which people can have, but this worry that we might experience something upsetting. We live and have always lived in a very upsetting world. You cannot have filters. You have to learn how to cope with it.”