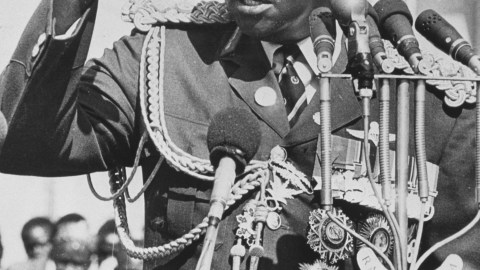

Dictators and mass murders: Understanding ‘malignant narcissism’

Image source: Hulton Archive / Getty Images

- The world over, dictators seem to share similar characteristics — a need for admiration, excessive paranoia, and ruthless brutality.

- At the same time, a relatively healthy, “normal” individual will have a great deal of difficulty putting themselves in a dictator’s shoes.

- It’s not enough to just chalk it up to evil: What condition could explain dictators’ bizarre desires and behaviors?

On his 60th birthday, Saddam Hussein commissioned a Quran to be written using 27 liters of his own blood. Idi Amin, who was Uganda’s brutal leader during the 70s, claimed he kept the decapitated heads of his political enemies in his freezer and that he had tried eating human flesh, but found it to be “too salty” for him. Francois Duvalier, who ruled Haiti from 1957 to 1971, once ordered all black dogs on the island to be put to death under the belief that a political opponent had transformed into one.

We don’t need to know about these eccentric behaviors and beliefs to understand that these rulers were deeply ill in some way. Proof of their disturbed states of mind can easily be found in the mass murders and genocides they perpetrated and their vicious paranoia. It’s difficult for most people to empathize with the psychology of dictators such as these. What drove them to become brutal despots?

A dysfunctional brain

Perhaps the most straightforward way to think about dictators’ psychology is to say that they are psychopaths. This is a reasonable, but perhaps imperfect, descriptor. Psychopaths tend to be bold, disinhibited, and cruel, traits that appear to be linked to dysfunction in two key parts of the brain: the lower frontal lobe and the amygdala.

The frontal lobe activates when presented with moral decision-making and impulse control, and the amygdala regulates fear, rage, desire — the more animalistic aspects of our behavior — and both contribute to the brain’s overall reward system. So, when these two parts of the brain are damaged or underdeveloped, it’s a recipe for psychopathy. Neuroscientist James Fallon describes the outcomes of this dysfunction in a blog post for Psychology Today:

“What satisfies a normal person — such as reading a good book or watching the sunset — does nothing for someone with an underdeveloped amygdala. For some people, this means a greater tendency toward drug and alcohol addiction and severe painful withdrawal that gets progressively worse over time, leading to malignant dependent behaviors. For sadists, they become addicted to torture and killing; dictators get high on power, an insatiable drive that gets progressively worse, or malignant with time.”

Muammar Gaddafi

Image source: Franco Origlia / Getty Images

Overweening self-love

This lack of self-control and callousness toward others certainly seems like a good fit for the dictator. But one of the hallmarks of psychopathy is the psychopath’s lack of regard for others, whereas many dictators seem to be excessively concerned about how they are perceived. In part, this is a method for retaining power, but it is also often the manifestation of narcissism.

Consider, for instance, Muammar Gaddafi, who believed himself to be a fashion icon, stating, “Whatever I wear becomes a fad. I wear a certain shirt and suddenly everyone is wearing it.” His bodyguards consisted entirely of attractive women. He also ensured that his face could be seen in public works of art throughout Libya and that quotations from The Green Book, in which he described his political philosophy, appeared in airports, on pens, or even in pop songs. Gaddafi wanted everybody to know and love him.

This certainly seems to fit the bill for narcissism, which is defined by a pervasive pattern of grandiosity, a need for admiration, and a lack of empathy for others. Many of us, however, know narcissists in our personal life — they might be wildly unpleasant, but they haven’t committed genocide. What’s the difference between a run-of-the-mill narcissist and the variety of narcissism that seems to afflict the world’s dictators?

“The root of the most vicious destructiveness and inhumanity”

Some psychologists believe that narcissism and psychopathy exist on a spectrum. Right in the middle of the two is malignant narcissism, a hypothetical syndrome that — although it hasn’t been formally recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders — may be the best framework for considering dictators’ psychologies. This condition is defined by the regular symptoms of narcissism, as well as the antisocial behavior seen in many psychopaths, sadists, and paranoia folk.

Where a psychopath might try to cultivate affection and esteem from others in order to further their own goals, they don’t require that affection and esteem. Where a narcissist needs the respect of others, they may not exhibit an extreme disregard for others and aggression. In between these two lies malignant narcissism, coupling both the extreme neediness of the narcissist and the psychopath’s antisocial tendencies. For a condition that psychologists have referred to as “the most severe pathology and the root of the most vicious destructiveness and inhumanity,” it certainly seems to coincide with the behaviors of the Hitlers, Maos, and Stalins of the world.