The Seductive Allure of Neuroscience Explanations

As regular readers will be well aware, much of what I’ve covered on this blog has been about the use and abuse of the prefix “neuro” to mislead. You don’t have to look far to see that most people seem to be pretty disconnected from the science of the brain. This becomes a problem once you realize how this allows us to be misled. Take, for example, the adverts for “brain training” games that stalk you on the internet with claims that don’t even remotely hold water; or the fact that a laughable technique called “Brain Gym” that involves making children perform pointless exercises and is based on no evidence whatsoever continues to be widespread in schools across the world at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars, and has been used by as many as 39 percent of teachers in the UK. Drop a few brain-related words and it seems even teachers can lose the capacity for critical thought en masse.

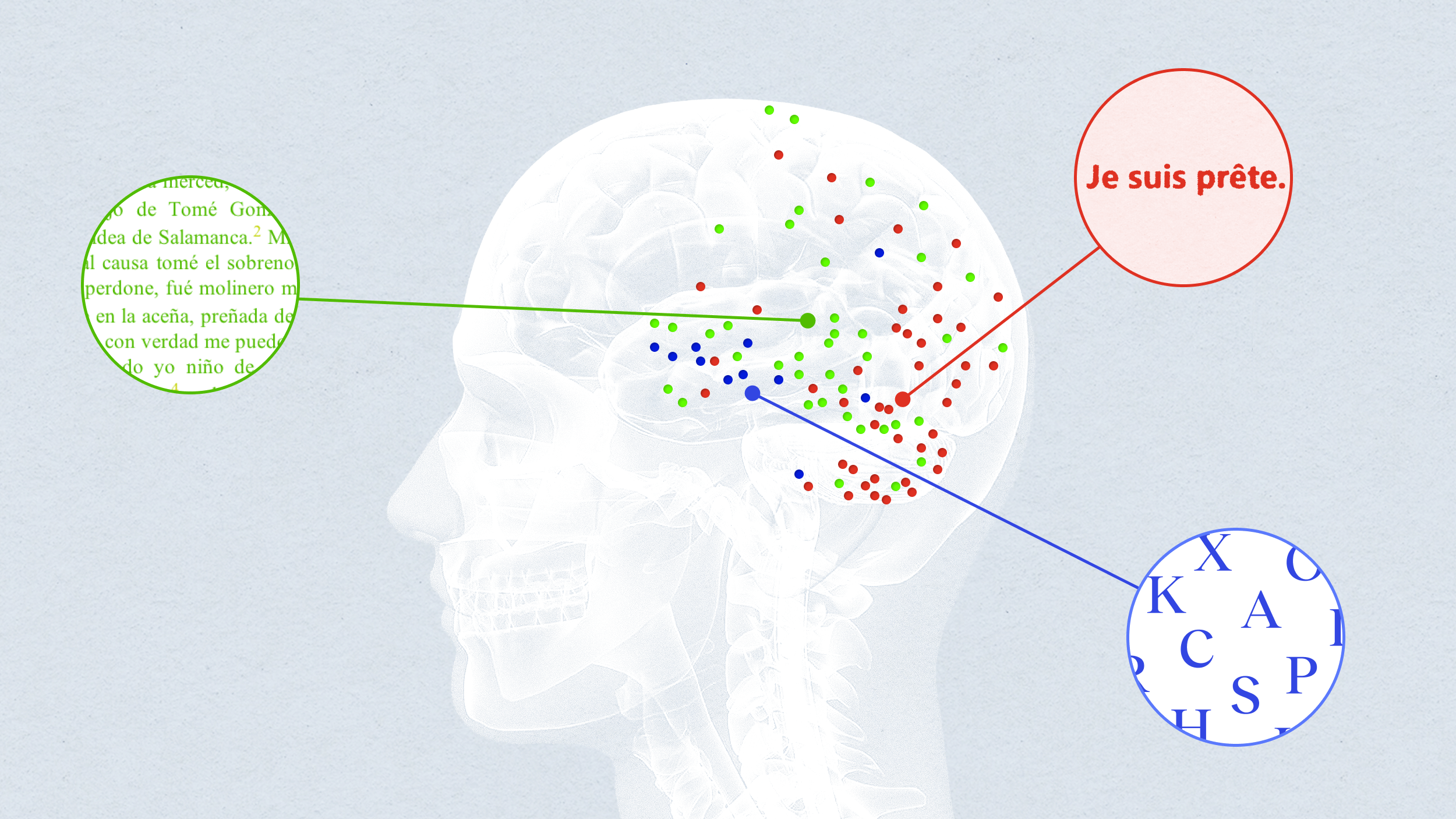

In 2008, a paper titled “The Seductive Allure of Neuroscience Explanations,” struck a chord with me when it made the case that we can be suckered into judging bad psychological explanations as better than they really are if they are served with a side order of irrelevant neuroscience. Another paper published the same year suggested that just showing an image of the brain alongside articles describing fictitious neuroscience research (for example claiming that watching TV improves mathematical ability) resulted in people rating the standard of reasoning in the articles as higher.

In 2013 however, a paper was published that remains a strong contender for the award of best-named paper of all time: “The Seductive Allure of Seductive Allure.” The paper pointed out flaws in both of the 2008 papers: The neuroscience explanations were longer and arguably added to the psychological explanations. It could be the case that more complicated-sounding, or seemingly better-explained explanations are simply more persuasive. If this were the case, this would be a rather less ground-breaking conclusion. This suggestion was posed way back in 2009 by the blogger Neuroskeptic. Furthermore, a systematic replication of the 2008 brain scan paper involving 10 experiments and a whopping 2,000 participants failed to find any evidence that the addition of a brain scan alone had any real impact on people; it seemed the “seductive allure of neuroscience explanations” was in tatters.

Soon the “Seductive Allure of Seductive Allure” debate was everywhere; even Vice got involved. The realization that simply adding pretty pictures of brains to an argument isn’t enough to fool most people probably shouldn’t have been so surprising. What seems to have been largely ignored however, is that the huge 2013 systematic replication, which was the centerpiece of the “Seductive Allure of Seductive Allure” case, in fact did replicate the original ” Seductive Allure of Neuroscience Explanations” finding: that bad neuroscience explanations (as opposed to images) are more convincing than psychological explanations alone. The authors of the replication offered up a plausible explanation for the failure of the brain images to persuade: “Why the disparity, then, between the trivial effects of a brain image and the more marked effects of neuroscience language? … Perhaps, then, the persuasive influence of the brain image is small when people have already been swayed by the neuroscience language in the article.”

Fast-forward to today and a new group of researchers have entered the fray, publishing a paper in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, in which the Seductive Allure of Neuroscience Explanations is tested a little more rigorously. The researchers gave students descriptions of psychological phenomena that were either good explanations or circular explanations. The circular explanations simply restated the claim in a different way rather than providing any actual explanation. The researchers tested to see what happened if superfluous neuroscience information or images of brain scans were added into the mix. Crucially, to control for the neuroscience explanations being more seemingly complex, the researchers also added a “hard science” condition in which superfluous physics or genetics information (for example) was added to the psychological explanation. A superfluous social science condition was also added for good measure.

Like the earlier replication, the brain images alone had little effect, but the superfluous neuroscience explanations were once again found to be more convincing to the students. Crucially they were also found to be more convincing than the superfluous social science and the superfluous hard science explanations. The results also make clear that people are really very bad at spotting circular arguments in science in general — they are just particularly bad at it when the circular argument is glossed under a veneer of neuroscience:

This is a conclusion that I don’t find surprising. I’m a firm believer that in some quarters of academia, in the words of Steven Pinker, some scholars “spout obscure verbiage to hide the fact that they have nothing to say. They dress up the trivial and obvious with the trappings of scientific sophistication, hoping to bamboozle their audiences with highfalutin gobbledygook.” That superfluous neuroscience seems to be more alluring than other superfluous science makes perfect sense, when it is a subject that is seen as a black box by so many.

This is the point where you are probably expecting me to advocate more and better neuroscience education. But that’s absolutely not what I think we need to solve this problem. The key problem here isn’t people’s knowledge of neuroscience; it’s their failure to identify irrational arguments. You certainly could spot the flaws in the arguments made in these studies by becoming an expert on all things brain-related. It would be a far more efficient and likely a far more practical use of your time to develop the critical-thinking skills and skeptical mindset necessary to simply spot the errors of logic. A great starting point in this area is Stuart Sutherland’s Irrationality, for a more extensive account see Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow.

As I so enjoy discussing at length on this blog, the evidence that people seem to fail to apply basic critical thinking to claims made about the brain is all around us. What I find equally concerning and somewhat closely related is the causes and consequences of a culture of “academic bullshitting” in which academics can feel coerced into speaking in a language of pseudoacademia, a language that only differs from everyday English in that it is impenetrable to the naive observer — enclosing an argument in a black box where it cannot be dismantled without great effort. This problem affects all disciplines to some degree, psychology perhaps more than others — as I suggested in a feature I wrote recently with Jon Sutton for The Psychologist. Taking advantage of terminology from neuroscience is just one trick in the toolbox.

Follow Neurobonkers on Twitter, Facebook, Google+, RSS, or join the mailing list. Image Credit: Shutterstock, Fernandez-Duque et al

Reference:

Fernandez-Duque D., Evans J., Christian C. & Hodges S.D. (2014). Superfluous neuroscience information makes explanations of psychological phenomena more appealing., Journal of cognitive neuroscience, PMID: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25390208