How Your Body Language Alters Your State of Mind

“Update: A new, larger replication has contradicted the research described in this blog post. Click here for more information.“

Many animals are known to adapt their bodies to influence other animals around them. Peacocks flare their feathers, chimpanzees inhale air to make their chests bulge, gazzelles stott – jumping higher than necessary when running away from a predator, cats run sideways when they are threatened to appear larger than they are. We all know humans do similar things for various reasons, but can the way we hold ourselves affect not just others’ perceptions of us, but what is going on inside our own heads? In a series of experiments spanning many decades, psychologists exploring a field of research called embodied cognition have experimented by placing individuals in various positions under false pretences before examining how the position of the body might impact the way they think.

In 2010 social psychologist Amy Cuddy’s landmark paper showed that getting people to pose in the pair of positions shown below (under the guise of attaching electrodes in different positions relative to the heart) resulted in increased levels of testosterone and reduced levels of the stress hormone cortisol. Her TED talk describing the experiment is now the second most popular TED talk of all time.

Testosterone rises before we engage in competition and following a win and falls following defeat, effectively reflecting and reinforcing an individual’s dominance. Cortisol is associated with feelings of powerlessness, anxiety and negative health effects such as lowered immune function and weight gain. The participants who took on the powerful poses also reported feeling more “powerful” and “in charge”.

Cuddy also discovered that the pair of weak posesshown below resulted in the reverse effect – increased levels of cortisol and decreased levels of testosterone. These results are supported by previous research that demonstrated that people placed in hunched postures were more likely to give up in a task that required persistence – a phenomenon known as learned helplessness. The people placed in hunched over positions also reported they felt more depressed, a finding that has been replicated repeatedly, including in Cuddy’s study.

In Cuddy’s 2010 study the participants who were placed in the weak poses with their arms crossed or in their laps were also more risk averse in a gambling game compared to those participants placed in a high power pose who were more willing to try to double their winnings by opting to roll a die.

In a classic study conducted in 1988, researchers got people to watch a cartoon while either holding a pen between their teeth, or between their lips without touching their teeth. Holding the pen between the teeth stimulated the same facial muscles used when we smile while biting with our lips alone makes it impossible to smile naturally. The researchers discovered that people found the cartoons funnier when they had the pen between their teeth. More recently, in a study that really makes you stop and think, researchers found that botox injections which can make it difficult to frown actually make people less depressed. Interestingly, the injections didn’t make the people feel more attractive, suggesting the reduced feelings of sadness were not to do with the treatment’s normal intended function. Amazingly, the results have recently been replicated in clinically depressed patients in a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. In the study published earlier this year over half of the depressed patients had at least a 50% reduction in a depression rating scale (compared to a 15% reduction in patients who received a placebo injection). 27% of the patients given botox even achieved clinical remission six weeks after the single treatment (in comparison to 7% of the patients in the placebo condition).

In a recently published study reminiscent of Monty Python’s Ministry of Silly Walks sketch, psychologists manipulated people’s walking patterns using a motion capture based biofeedback system. If the system detected an upright posture and swinging arms a gauge on a monitor would move in one direction. The participants weren’t told what the gauge measured but were told to keep experimenting with different walking styles to move the gauge to the right. This allowed the participants to be manipulated to reflect either the characteristics of a depressed patient or a “particularly happy walking style”. The researchers then asked the people to recall words from a list of happy or sad words. The overall results were unremarkable – the people who had been led to walk in a happy style remembered slightly more happy words and vice versa. But the people who had achieved the happiest walking style remembered three times as many of the positive words than the students who achieved the saddest style of walking.

In another study Amy Cuddy gave students a mock “dream job” interview in which they had five minutes to write and five minutes to deliver a speech to two interviewers. While preparing for the interview the students were asked to perform the “expansive” or “contractive” poses. The poses were not maintained during the interview – when the students could stand how they liked. During the interview the researchers who were dressed in white lab coats scribbled notes and withheld all emotions not giving so much as a smile or a nod. This procedure, known as the Trier Social Stress Test has been shown to result in a tsunami of cortisol, it is even believed to be the most ethical way to elicit the greatest amount of cortisol possible under laboratory conditions. The students who had held the expansive poses were rated higher in both the content and delivery of their speeches. Importantly, this was in spite of there being no statistically significant difference in their stances during the interview.

The findings of Cuddy’s research aren’t all rainbows and happiness however, in a series of experiments published last year Cuddy demonstrated that striking a “power pose” – the name Cuddy has given to particularly dominant stances – can make you more likely to act dishonestly. In the first experiment, people stretched for one minute in an expansive or contractive pose. Participants were told they would be paid $4 for participation but the experimenter then “accidentally” overpaid them, giving them $8 instead. Astoundingly, 78% of the people who were made to do the expansive pose kept the money compared to only 38% of those who were told to adopt the contractive pose.

In the next experiment people could earn money by unscrambling anagrams working only on either a small, or a large desk pad – surreptitiously forcing them to either spread their arms across the table or work in a hunched over fashion. The psychologists then gave the participants the answers and asked them to mark their own work – but unbeknownst to the participants a sheet of carbon paper was hidden under their worksheet. Those who worked on the small pad were more likely to cheat. In another experiment participants had to sit in a large comfortable seat or a small seat where they would feel squashed. They were told to stop for 10 seconds every time they crashed while playing a game of Need for Speed on the Playstation 3. The people who were in the seats that allowed them to take an expansive style of sitting were more likely to cheat. In a final study, that seems more interesting anecdotally than as evidence for the theory, Cuddy observed that drivers of cars with larger seats were more likely to double park in New York City, but this effect is clearly likely to be entangled with the fact that drivers who choose larger vehicles are likely to be very different types of people to those who would choose something more modest – but an interesting anecdote all the same, given that the experimenters were blinded, providing hard evidence for the belief that drivers of large cars tend to be less conscientious.

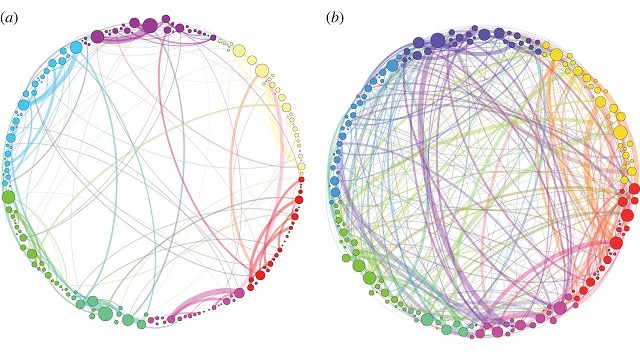

In another study Cuddy manipulated posture by providing participants with a task on either an iPod Touch, an iPad, a Macbook Pro or an iMac. The participants were told the experimenter would return after five minutes but the experimenter never returned. The researchers timed how long it would take for the participants to come looking for the absent experimenter. Amazingly the people who used the larger devices waited far less time before going looking for the experimenter – represented by the grey bars in the graph below. In fact only half of those who used the iPod Touch ever mustered up the courage to seek out the experimenter compared to nearly all of those who used the iMac – the percentages of participants who took the decision to look for the experimenter are represented by the dark grey bars in the graph below.

Exasperatingly – given their straight forward nature, Cuddy’s findings have been widely misconstrued in the media. Cuddy’s argument is that “power poses” should be used to help people prepare psychologically for a challenging social interaction, but crucially – not actually used in the social interaction itself. Maintaining a position that could be perceived as aggressive is not a pleasant way to engage with other human beings in most contexts. This is particularly important if you already have the dominant role in the relationship – for example if you are a manager or a doctor. It’s been demonstrated for instance that doctors are more likely to be sued by their patients if they speak in tones rated as being more dominant. This was predicted from only forty seconds of speech that was scrambled to remove all meaning. That is not to say taking on a powerful stance is not useful for social interactions – just not every social interaction. Indeed, as Cuddy suggests, more often than not it may be best to push the table aside. Pitches, presentations, job interviews are all potential places Cuddy’s techniques could be useful, but depending on the situation they may be best reserved for the bathroom. Obviously (you would think) the idea is not to put your feet on the table when conducting a job interview – as one of Cuddy’s Harvard Business School students had the displeasure of actually witnessing – at Harvard Business School of all places.

The explosion of research in the field of embodied cognition over recent years appears to demonstrate that there is a very strong feedback loop between how we express our emotions with our bodies and how we experience our emotions, but the idea is not a new one. In 1872 Charles Darwin proposed that our facial expressions feed information back to our brain, altering our emotions positively or negatively. We all know how frustrating it is to be told to smile when we are having a bad day, but it seems there really is a good argument for reminding ourselves to smile, stand up tall, spread our shoulders wide and express positivity. We’ve known for a long time the importance of first impressions and the effect our body language can have on other people, but what we often forget – and what we’re only recently seeing such strong evidence for, is the effect our body language can have on the inside.

Follow Neurobonkers on Twitter, Facebook, RSS or join the mailing list.

References:

Bos, Maarten W., and Amy J.C. Cuddy. “iPosture: The Size of Electronic Consumer Devices Affects Our Behavior.”Harvard Business School Working Paper, No. 13-097, May 2013.

Cuddy, Amy J.C., Caroline A. Wilmuth, and Dana R. Carney. “Preparatory Power Posing Affects Performance and Outcomes in Social Evaluations.” Harvard Business School Working Paper, No. 13-027, September 2012. (Revised November 2012.)

Carney D.R., Cuddy A.J.C. & Yap A.J. (2010). Power Posing: Brief Nonverbal Displays Affect Neuroendocrine Levels and Risk Tolerance, Psychological Science, 21 (10) 1363-1368. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956797610383437

Finzi E. (2014). Treatment of depression with onabotulinumtoxinA: A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial, Journal of Psychiatric Research, 52 1-6. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.11.006

Michalak J. & Nikolaus F. Troje (2015). How we walk affects what we remember: Gait modifications through biofeedback change negative affective memory bias, Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 46 121-125. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2014.09.004

Riskind J.H. (1982). Physical posture: Could it have regulatory or feedback effects on motivation and emotion?, Motivation and Emotion, 6 (3) 273-298. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/bf00992249

Strack F. & Sabine Stepper (1988). Inhibiting and facilitating conditions of the human smile: A nonobtrusive test of the facial feedback hypothesis., Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54 (5) 768-777. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.768

Yap A.J., B. J. Lucas, A. J. C. Cuddy & D. R. Carney (2013). The Ergonomics of Dishonesty: The Effect of Incidental Posture on Stealing, Cheating, and Traffic Violations, Psychological Science, 24 (11) 2281-2289. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956797613492425

Image Credits: Shutterstock, Tinypic, Cuddy et al. 2014, Cuddy et al. 2013