Neil deGrasse Tyson Thinks We Should All “Get Over” Pluto

Should Pluto still be a planet? The issue has been hotly debated for many years, but Neil deGrasse Tyson has recently drawn a line in the sand. Appearing on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert he declared that when it comes to Pluto’s diminished planetary status we need to “just get over it!”

Tyson describes himself as an “accessory” to the decision made by the International Astronomical Union (IUA) in 2006 to downgrade Pluto from planet to ‘dwarf planet.’

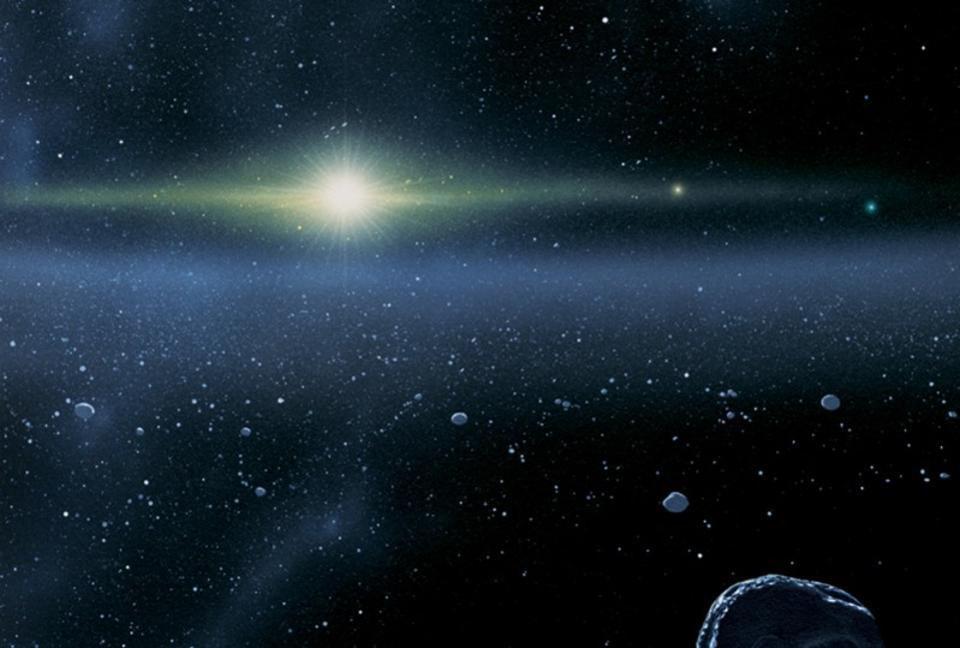

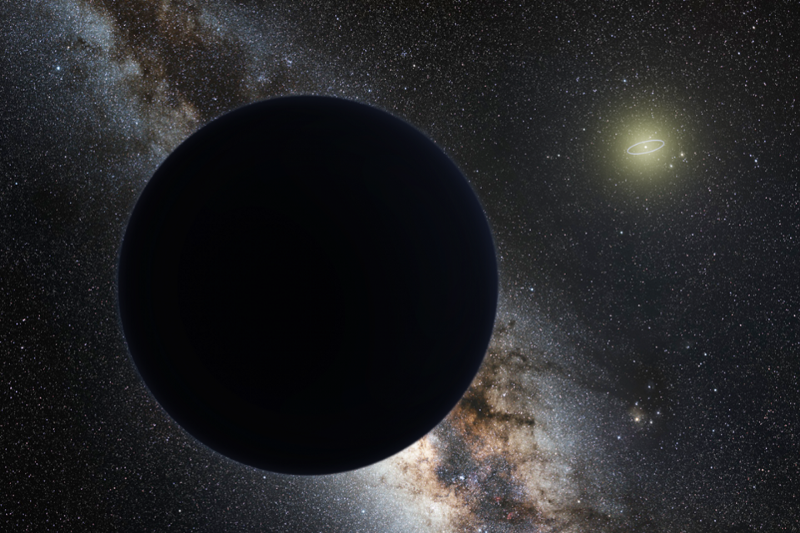

Why the shift? Simply put, it was a size thing. Pluto orbits the sun, and is rounded by gravity, but it fails to meet the third criteria for planetary status as it has not cleared the area around its orbit—alas, it isn’t big enough! For this reason, Tyson and others thinks it belongs “with its other icy brethren in the outer solar system.”

It’s been over ten years since Pluto was downgraded, but the debate continues to rage over the logic and justice of the move. Every year, a spate of articles gets published querying whether Pluto will soon be dubbed a planet again.

While Tyson has been a long-time supporter of the demotion, other scientists are adamant that Pluto’s status should be restored. The planetary physicist Philip Metzger has questioned much of the logic behind the change. He concedes that Pluto is smaller than the eight other planets, but points out that is much larger than many other objects that are large enough to be classified as planets. Jupiter and Saturn make everything look small, but for all intents and purposes Pluto is plenty big.

Planets compare by size, to scale. Image credit: leSud via http://www.philipmetzger.com/

While Metzger thinks that the first two IUA criteria make sense when defining a planet, he finds the third requirement problematic because it relates to action, rather than a fundamental state of being. He points out that:

“Saying a planet must be round by its own gravity is a part of its being. Saying it must have cleared its orbital neighborhood is a part of its doing.”

According to Metzger, mixing being and doing “would be crazy in any other branch of science. Suppose we said that unless a species eats meat, then it’s not a real mammal; it’s just a dwarf mammal.”

He also thinks that focusing on the biggest objects that are closest to the sun (and us) is rather anthropocentric. Instead, he thinks we should embrace more types of planets, large and small, and expand our definition of the term beyond “the outdated impression of a static solar system where everything important is closer to the sun.”

Alan Stern, the lead scientist who spearheaded NASA’s New Horizons fly-by of Pluto in 2015 voiced his dissent more simply, terming the reclassification, “bullshit.” Stern thinks that planetary scientists should determine the status of a planet, not astronomers, who in his view have “made up a definition, which is actually bogus.”

Funnily enough, scientists don’t appear to argue much over the fundamental characteristics of the (dwarf) planet. Instead, they quibble over the rank and title. Why do they bother? And why do the rest of us care so much?

One reason might be nostalgia. Humans love stories and Pluto was a loveable character in a fundamental tale that many of us were told and retold in childhood. It is hard to let go of formative ideas about the natural world, as history readily attests.

Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection caused uproar in the Victorian world and triggered a heated debate about human origins that continues into the present day. His ideas prompted us to relinquish the notion of a creator-God and forced a major revision of orthodox scientific and spiritual world views.

Pluto’s reclassification is a smaller upset, but it still forces us to reposition a sometimes rather anthropomorphic character (‘the little guy’) which has long had a steadfast place in our hearts and minds.

Why does it bug us so much when stories change? It’s called the status quo bias. Simply put, we are wired to prefer what we already know. As the Israeli-American psychologist Daniel Kahneman and colleagues explain, “individuals have a strong tendency to remain at the status quo, because the disadvantages of leaving it loom larger than the advantages.” When this theory was tested on humans making decisions, researchers found that:

“[A]n alternative became significantly more popular when it was designated as the status quo. Also, the advantage of the status quo increases with the number of alternatives.”

Why call lots of other things planets when we can stick with the 8 (or 9) that we know and love!

The status quo bias is also strongly linked to our wiring for loss aversion. In our minds, “changes that make things worse (losses) loom larger than improvements or gains.” So while it is possible that reclassifying Pluto has some scientific value, it’s hard for us to get around the feeling that somehow we’ve been robbed.

Other cognitive biases that may also be in play include confirmation bias. See the video below for more.

But Tyson has his status quo bias in check and remains jovial about the whole saga. Bringing the underdog character back into the cosmic story he gives a ‘whatever-man’ shrug and simply declares: “Pluto had it coming from the beginning.”

—