Social distancing measures recommended until 2022

Photo by David Dee Delgado/Getty Images

- Harvard researchers have recommended that intermittent social distancing measures should be in place until 2022.

- An observational study in Hong Kong found that social distancing measures have helped the nation avoid stricter lockdowns.

- America has a severe testing shortage that is delaying our ability to effectively measure the impact of COVID-19.

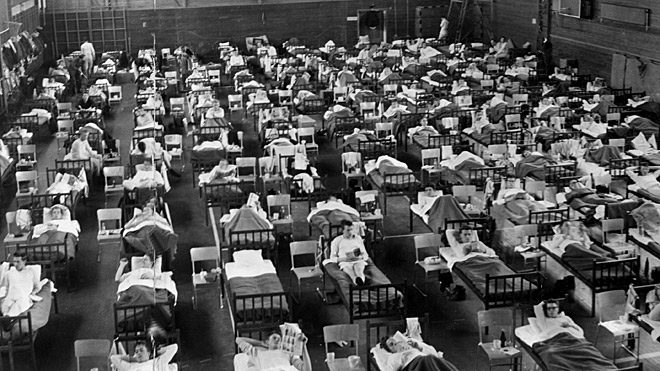

While the media spotlight over the last week has been on fringe groups protesting at state capitals, most of the American population is staying at home and respecting social distancing guidelines while outside. It’s the primary reason we haven’t had to endure previously forecasted numbers of emergency room cases and deaths. Health care workers on the front lines in major cities are overwhelmed as it is. Our duty is to not make their incredibly stressful jobs more demanding than they already are.

Social distancing is an important weapon for containing this virus, according to researchers at the WHO Collaborating Centre for Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Control. In a new observational study published in The Lancet, the Hong Kong-based team looked in their own backyard to see how their country was able to flatten the curve without requiring stricter stay-at-home orders.

Hong Kong, like South Korea and Singapore, instituted preventive measures immediately. These countries were testing citizens as soon as possible; they began requiring distancing and protective equipment when cases were first detected. Testing is key. As Cynthia Cox, the director of the Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker, told Vox,

“The testing failure is putting additional strain on our already challenged health system. The combination of all of these factors will make the US worse off than similar countries.”

Researchers predict US may have to endure social distancing until 2022

WHO researchers reviewed three telephone surveys between January 20 and March 13 to understand attitudinal changes as the disease progressed. They analyzed COVID-19 cases alongside influenza data and watched the reproduction number of coronavirus cases. And they discovered that a combination of behavioral changes, such as social distancing and wearing protective gear in public, border restrictions, and isolation of confirmed cases (and their contacts) helped to slow the spread.

“Our findings strongly suggest that social distancing and population behavioural changes—that have a social and economic impact that is less disruptive than total lockdown—can meaningfully control COVID-19.”

The researchers warn that relaxed policies, which began in March, are likely to lead to an increase in cases. Tracing is an essential strategy if nations hope to avoid serious outbreaks. Interestingly, the team noticed that social distancing also reduced influenza transmissions, which is important given that, for vulnerable populations, hospital beds are being occupied by COVID-19 patients.

Hong Kong’s example could help set a precedent for other nations. The researchers write that all of these considerations need to be in place. At the moment, there does not seem to be a singular silver bullet.

“Because a variety of measures were used simultaneously, we were not able to disentangle the specific effects of each one, although this may become possible in the future if some measures are strengthened or relaxed locally, or with use of cross-national or subnational comparisons of the differential application of these measures.”

Meanwhile in America, officials are calling for seniors to sacrifice their lives for the economy, testing is woefully absent, and the president’s sole focus is getting business going again, health consequences be damned. These are the exact opposite measures than those health experts are proposing.

Two men not observing social distancing playing basketball in Prahran with a sign outside the court reading that the court is closed on April 15, 2020 in Melbourne, Australia.

Photo by Asanka Ratnayake/Getty Images

A new modeling study from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health states that while a two or three-month distancing period flattens the curve, groups susceptible to COVID-19—people over 65 and those suffering from underlying conditions, as well as the obese—will continue to be at risk until effective treatments and, potentially, a vaccine are produced. They’re recommending that we institute social distancing policies until 2022.

Aware of a contentious response to this recommendation, they note that this isn’t about politics.

“The authors wrote that they’re aware of the severe economic, social, and educational consequences of social distancing. They said their goal is not to advocate a particular policy but to note ‘the potentially catastrophic burden on the healthcare system that is predicted if distancing is poorly effective and/or not sustained for long enough.'”

There is never a return to normal, for that supposes a societal baseline that is constant. We are moving somewhere else that will one day seem like the everyday, until it shifts again. We must take responsibility for how we transition and listen to the signal in all of this noise. For now, I only have one certainty: I’m not willing to sacrifice my parents for your portfolio.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook. His next book is “Hero’s Dose: The Case For Psychedelics in Ritual and Therapy.”