High-fat diets change your brain, not just your body

Photo by Miguel Andrade on Unsplash

- Anyone who has tried to change their diet can tell you it’s not as simple as simply waking up and deciding to eat differently.

- New research sheds light on a possible explanation for this; high-fat diets can cause inflammation in the hypothalamus, which regulates hunger.

- Mice fed high-fat diets tended to eat more and become obese due to this inflammation.

Your wardrobe won’t be the only thing a bad diet will change in your life — new research published in Cell Metabolism shows that high-fat and high-carbohydrate diets physically change your brain and, correspondingly, your behavior. Anyone who has tried to change their diet can tell you that it’s far more challenging than simply deciding to change. It could be because of the impact high-fat diets have on the hypothalamus.

Yale researcher Sabrina Diano and colleagues fed mice a high-fat, high-carb diet and found that the animals’ hypothalamuses quickly became inflamed. This small portion of the brain releases hormones that regulate many autonomic processes, including hunger. It appears that high-fat, high-carb diets create a vicious cycle, as this inflammation caused the mice to eat more and gain more weight.

“There are specific brain mechanisms that get activated when we expose ourselves to specific type of foods,” said Diano in a Yale press release. “This is a mechanism that may be important from an evolutionary point of view. However, when food rich in fat and carbs is constantly available it is detrimental.”

Photo by Miguel Andrade on Unsplash

A burger and a side of fries for mice

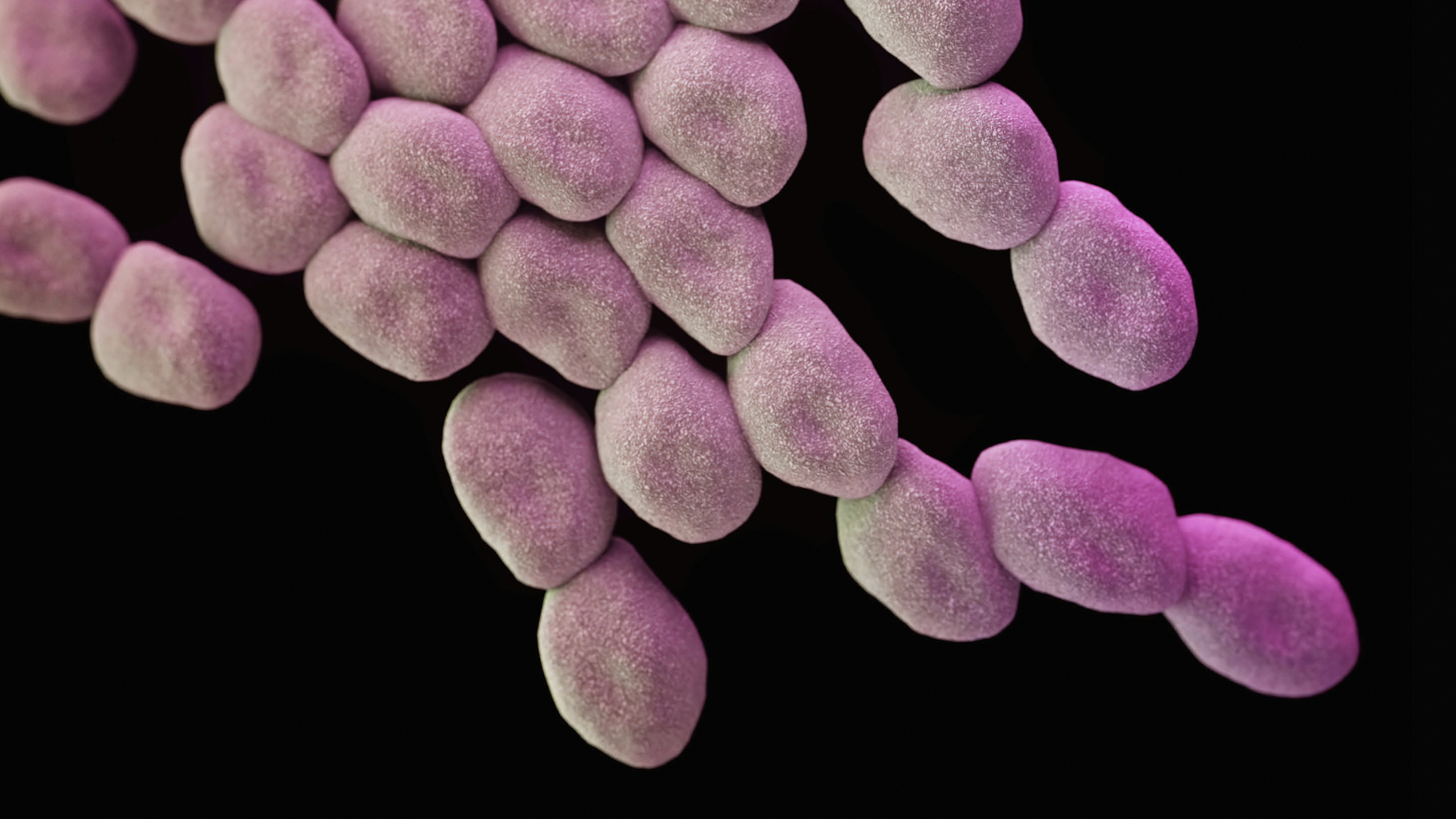

The main driver of this inflammation appeared to be how high-fat diets changed the mice’s microglial cells. Along with other glial cells, microglia are a kind of cell found in the central nervous system (CNS), although they aren’t neurons. Instead, they play a supporting role in the brain, providing structure, supplying nutrients, insulating neurons, and destroying pathogens. Microglia work as part of the CNS’s immune system, seeking out and destroying foreign bodies as well as plaques and damaged neurons or synapses.

In just three days after being fed a high-fat diet, the mice’s microglia activated, causing inflammation in the hypothalamus. As a result, the mice started to eat more and became obese. “We were intrigued by the fact that these are very fast changes that occur even before the body weight changes, and we wanted to understand the underlying cellular mechanism,” said Diano.

In mice fed with a high-fat diet, the researchers found that the mitochondria of the microglia had shrunk. They suspected that a specific protein called Uncoupling Protein 2 (UCP2) was the likely culprit for this change, since it helps to regulate the amount of energy microglia use and tends to be highly expressed on activated microglia.

To test whether UCP2 was behind the hypothalamus inflammation, the researchers deleted the gene responsible for producing that protein in a group of mice. Then, they fed those mice the same high-fat diet. This time, however, the mice’s microglia did not activate. As a result, they ate significantly less food and did not become obese.

An out-of-date adaptation

When human beings did not have reliable access to food, this kind of behavioral change would have been beneficial. If an ancient human stumbled across a high-fat, calorically dense meal, it would make sense for that individual to eat as much as they could, not knowing where it’s next meal would come from.

But there were no Burger Kings during the Pleistocene. We have been extraordinarily successful in changing our environment, but our genome has yet to catch up. The wide availability of food, and especially high-fat foods, means that this adaptation is no longer a benefit for us.

If anything, research such as this underscores how difficult it is to really change bad habits. A poor diet isn’t a moral failing — it’s a behavioral demand. Fortunately, the same big brains that gave us this abundance of food can also exert control over our behavior, even if those brains seem to be working against us.