The unknown linguistic laws that apply to all life

- There are various laws of linguistics, such as common words being shorter than less common words.

- These laws apply not only to human language but communication among animals, as well.

- Most amazing, though, is that these rules appear just about everywhere, from species distribution and size to disease outbreaks to the structure of proteins.

Linguists have known for quite some time that certain “laws” seem to govern human speech. For instance, across languages, shorter words tend to be more frequently used than longer words. Biologists have taken notice, and many have wondered if these “linguistic laws” also apply to biological phenomena. Indeed, they do, and a new review published in Trends in Ecology & Evolution elaborates on their discoveries.

Pattern 1: being twice as big as the nearest rival

The first linguistic rule concerns the frequency of the most used words in a language. It is known as “Zipf’s rank-frequency law”, and it maintains that “the relative frequency of a word is inversely proportional to its frequency rank.” In other words, the most frequently used word will be twice as common as the second most frequent word, three times as common as the third most frequent, and so on. For instance, in English, “the” is the most common, making up seven percent of all the words we use. The next common is “of,” which is roughly 3.5 percent.

The incredible thing is that this law applies also to a whole range of non-linguistic things. It is seen in the size of proteins and DNA structures. It is seen in most of the noises animals use to communicate, as well as primate gestures. It is found in the relative abundance of plant and animal species. In your garden, the flora and fauna very likely will be distributed by Zipf’s rank-freqeuncy law.

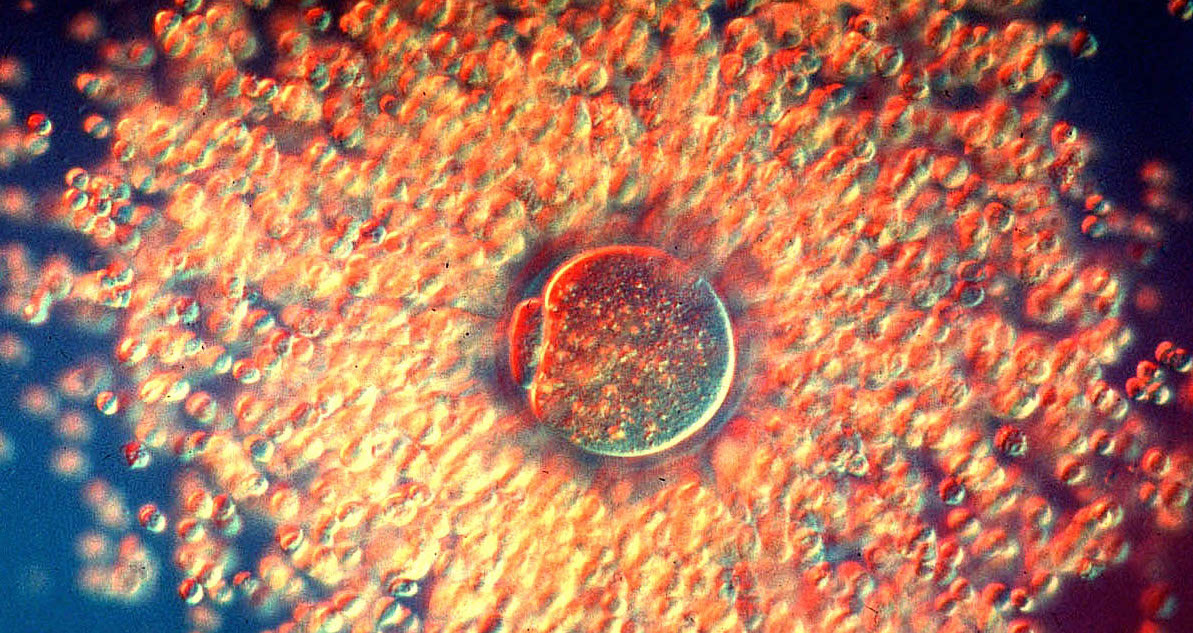

Recently, it has been observed in COVID infection rates, where the largest outbreaks (if there are similar demographics across a country) will be double the size of the next largest region. The law is so reliable, that it is being used to call out countries who are doctoring their COVID infection numbers.

Pattern 2: smaller things are more common

The second linguistic rule we can apply to life is known as “Zipf’s law of abbreviation,” which “describes the tendency of more frequently used words to be shorter.” It is true across hundreds of diverse and unrelated languages, including sign. In English, the top seven most common words are all three letters or fewer, and in the top 100, there are only two words (“people” and “because”) that are more than five letters. The words we use most regularly are short and to the point.

It is also a law seen all over nature. Communication among birds and mammals tend to be short. Indeed, it is seen in the songs of black-capped chickadees, call duration of Formosan macaques, vocalizations of indri, gesture time of chimpanzees, and length of surface behavioral patterns in dolphins. Apparently, it is not just humans who want their language to be efficient.

The law appears in ecology, as well: the most numerous species tend to be the smallest. There are many, many more flies and rats in New York City than there are humans.

Pattern 3: the longer something is, the shorter its composite parts

Let’s take a sentence, like this one, with all its words, long and short, strung together, punctuated by commas, nestled in with each other, to reach a final (and breathless) finale. What you should notice is that although the sentence is long, it is divided into pretty small clauses. This is known as “Menzerath’s law,” in which there is “a negative relationship between the size of the whole and the size of the constituent part.” It is seen not only in sentence construction; the law applies to the short phonemes and syllables found in long words. “Hippopotamus” is divided into lots of short syllables (that is, each syllable has only a few letters), while, ironically, the word “short” constitutes one giant syllable.

As with the previous laws, it is observed in most languages but is perhaps not as widespread. There are several counterexamples, but not nearly enough to discredit the general principle. In nature, it is well documented. In molecular biology, we see “negative relationship[s] between exon number and size in genes, domain number and size in proteins, segment number and size in RNA, and chromosome number and size in genomes.” but also on a macrobiological scale. But, just as with humans, Menzerath’s law is not nearly as common as Zipf’s.

In ecological terms, the more species you find in any given locale, the smaller they all tend to be. So, if a square mile of rainforest contains hundreds or thousands of species, then they all will tend to be much smaller than, say, a square mile of a city.

Linguistic laws in biology and beyond

While the paper focuses largely on these three laws, it hints at others that might yet be found (ones which are, as yet, understudied and underexplored). For instance, “Herdan’s law” (a correlation between the number of unique words and the length of a text) is seen in the proteomes of many organisms, and “Zipf’s meaning-frequency law” (in which more common words have more meanings) is seen in primate gestures.

The sheer scale of how applicable and versatile these laws are is remarkable. Laws that were discovered in linguistics have applications in ecology, microbiology, epidemiology, demographics, and geography.

Jonny Thomson teaches philosophy in Oxford. He runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.