Lightning may have provided a key mineral for early life on Earth

Credit: Pixabay via Pexels

- A chance discovery in suburban Illinois may change how we understand the dawn of life.

- Among other things, life needs water-soluble phosphorus, which was hard to come by 3.5 billion years back.

- This finding may imply that life has more opportunities to begin on other worlds than previously supposed.

Even the youngest child often wonders where they came from. For many scientists, a group of people known for retaining their childlike wonder, the question naturally evolves to asking how life itself originated on Earth. As is often the case when working with questions about the Earth billions of years ago, those trying to answer this one have access to a limited amount of data.

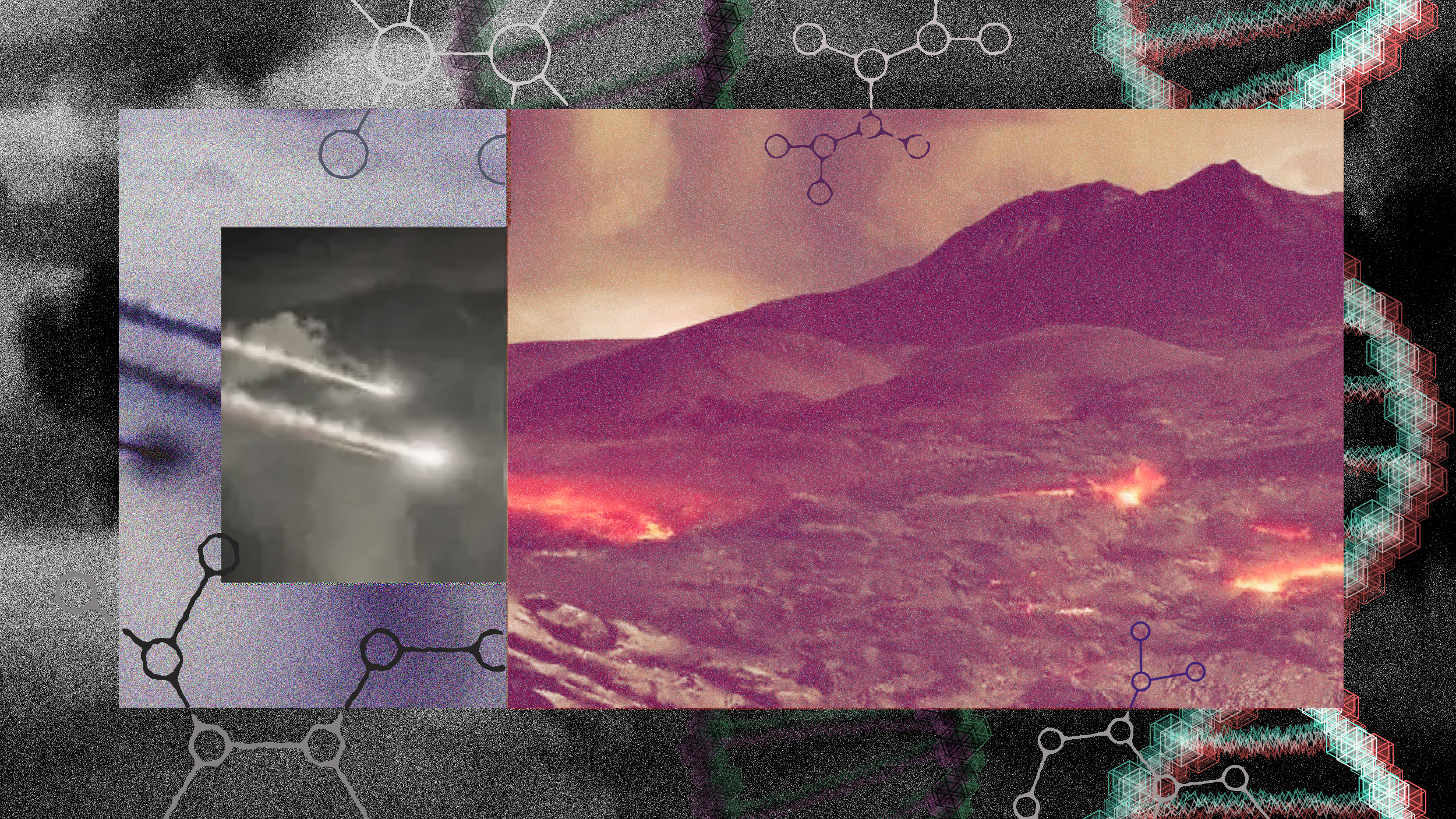

Now, a chance finding from a lightning strike in Illinois may reshape how we understand the beginnings of life on this planetand worlds beyond.

Phosphorous is an important chemical for life on Earth, cells use it to help build DNA and RNA and it is required for several other important functions. There is plenty of phosphorous on Earth, but not all of it is water-soluble. It is thought that much of the phosphorus on Earth three and a half billion years ago, about the time when life first appeared, was trapped in minerals that can not dissolve in water. Given how important water is for life on Earth, this was an obstacle to the rise of life.

Until very recently, the leading theory about where most of the soluble phosphorous came from credited meteorites, many of which have small amounts of the stuff. However, this theory always had problems. The number of meteorites hitting the early Earth, while high, is thought to have fallen drastically after the event which is theorized to have created the moon. The problem gets worse over time, with fewer and fewer expected impacts as the solar system stabilized.

Additionally, meteorite impacts are often catastrophic events more often known for ending life than helping to start it. The amount of phosphorous that could arrive this way is also limited, with the heat and trauma of impact potentially vaporizing much of the stuff and leaving a pittance readily accessible in the environment.

This is where the chance finding in Illinois comes in. In 2016, a hunk of fulgurite, a clump of fused sediment created by a lightning strike, was found in Glen Ellyn, a small Chicago suburb. The sample was given to the nearby Wheaton College.

A team of researchers from the University of Leeds examined the specimen as part of an investigation into the formation of fulgurite, but were surprised to discover that it contained a large amount of schreibersite, a water-soluble phosphate mineral.

Lead author and Ph.D. candidate Benjamin Hess explained how this find might alter theories on how water-soluble phosphates came into being billions of years ago:

“Most models for how life may have formed on Earth’s surface invoke meteorites which carry small amounts of schreibersite. Our work finds a relatively large amount of schreibersite in the studied fulgurite. Lightning strikes Earth frequently, implying that the phosphorus needed for the origin of life on Earth’s surface does not rely solely on meteorite hits.”

Their findings were published in Nature Communications and can be read in their entirety here.

In addition to shedding light on the Earth’s past environment and how it changed over time, this finding might also aid the search for life on other planets.

Lead author Mr. Hess speculated that the finding “also means that the formation of life on other Earth-like planets remains possible long after meteorite impacts have become rare.”

This is important because, as co-author Dr. Jason Harvey explains:

“The early bombardment is a once in a solar system event. As planets reach their mass, the delivery of more phosphorus from meteors becomes negligible. Lightning, on the other hand, is not such a one-off event. If atmospheric conditions are favourable for the generation of lightning, elements essential to the formation of life can be delivered to the surface of a planet. This could mean that life could emerge on Earth-like planets at any point in time.”

While these speculations presume that alien life forms will require the same substances we do to exist, the discovery of a new source of usable phosphorus is an exciting find for those interested in alien worlds and in the early geology or biology of Earth. While we might never know precisely where the phosphorous used in the first life form came from, this discovery will help to make sense of where we came from and where we might find others like us out amongst the stars.