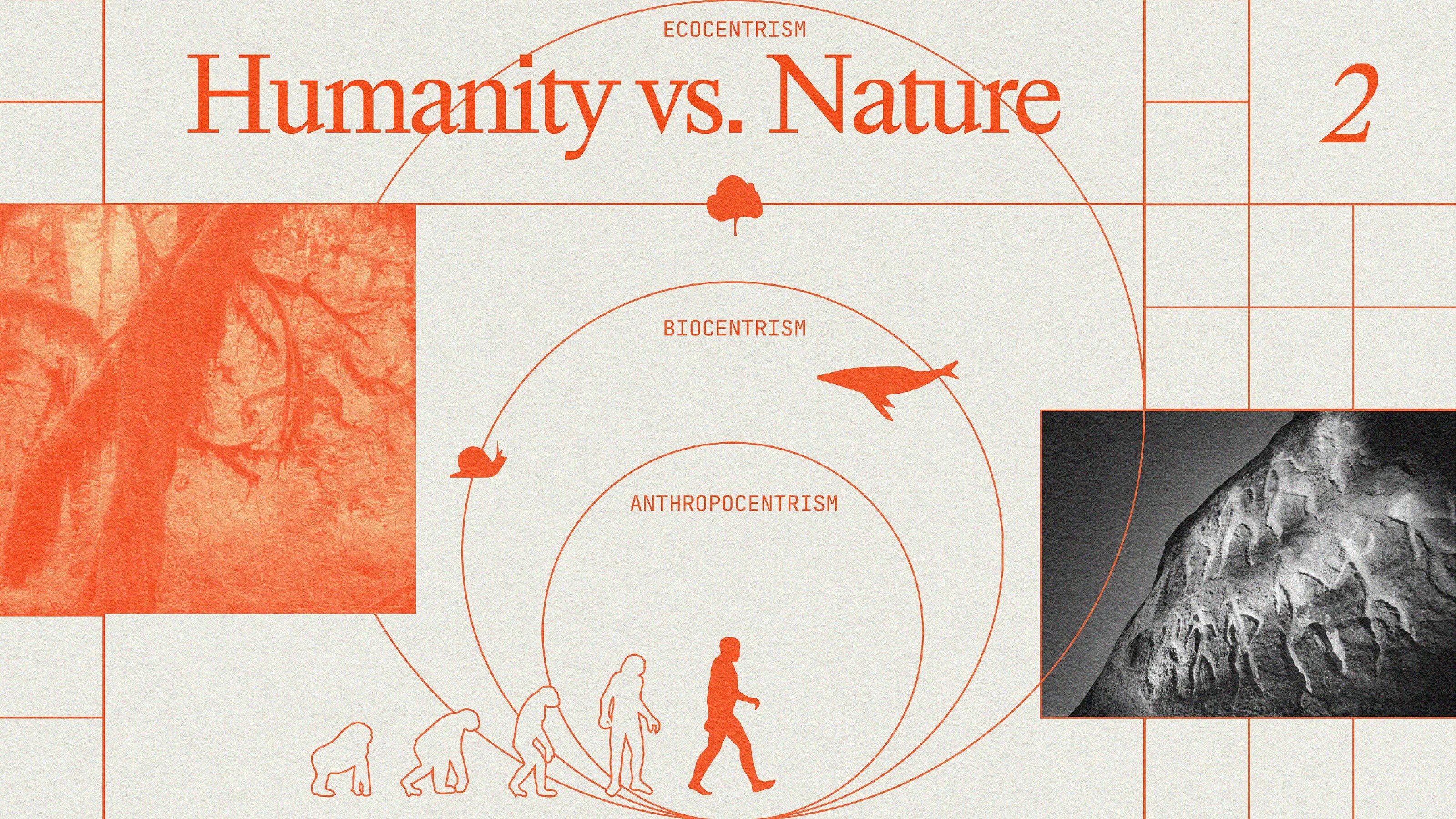

To save ourselves, half of Earth needs to be given to animals

(Photo Lily on Unsplash)

- Scientists says our survival depends on biodiversity.

- A natural climate strategy we often forget.

- Seeing our place among Earth’s living creatures.

When we talk about the loss of habitat for animals, it’s usually discussed in altruistic terms. Those who love animals are eager to fix it, while others feel it’s our planet to do with what we will. It turns out that there may be a 100 percent selfish reason to protect massive swaths of earth for non-humans: It could be the only way to save ourselves. That’s the thought-provoking conclusion drawn in a recent article, Space for Nature in Science. It was written by National Geographic’s chief scientist, Jonathan Baillie, and zoologist Ya-Ping Zhang, vice president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. They say we should set aside a third of the oceans and land by 2030, and half of the planet by 2050.

A desert bighorn ewe and her lamb walk across Mojave Trails National Monument.

Photo credit: David McNew / Getty Images

Why we should save so much room for animals

Even putting aside compassion for non-human lives, Baillie points out, “We have to drastically increase our ambition if we want to avoid an extinction crisis and if we want to maintain the ecosystem services that we currently benefit from.” Though he doesn’t explicitly say so, we can interpret what he’s talking about as including human extinction.

Our population is currently 7.6 billion people and is expected to reach 10 billion by 2050. How will we be able to put food in so many mouths? The 50 percent proposal, argues Baillie, is our only hope: “That’s why we need an intact planet. If we want to feed the world’s population, we have to be thinking about maintaining the ecological systems that allow us to provide that.”

And it’s not just about our food supply. “We are learning more and more that the large areas that remain are important for providing services for all life,” says Baillie. “The forests, for example, are critical for absorbing and storing carbon.”

Really? Half the earth for animals?

The article written by Baillie and Zhang explains the 50 percent target: “Most scientific estimates of the amount of space needed to safeguard biodiversity and preserve ecosystem benefits suggest that 25 to 75 percent of regions or major ecosystems must be protected.” There’s a significant degree of guesswork in those numbers, “because of limited knowledge of the number of species on this planet, poor understanding of how ecosystems function or the benefits they provide, and growing threats such as climate change.” Still, it’s better to play it safe according to the article, since “targets set too low could have major negative implications for future generations and all life. Any estimate must therefore err on the side of caution.”

Aren’t large areas already protected?

With less than half of the earth’s regions free of human impact, about 20 percent of vertebrate animals and plants are currently considered threatened. Yet only 3.6 percent of the oceans and 14.7 percent of the land, according to the authors, are under formal protection.

That’s not only just a drop in the bucket, but those figures don’t even tell the whole story. Many of these areas are “paper parks,” legally set aside but unmanaged—about a third of even these areas are being “quietly ruined” as a result of “intense human pressure.”

David Lindenmayer of the Australian National University tellsNewScientist, “These protected areas must be well managed. The basis for conservation will need to change so that it becomes a key part of economies and livelihoods.”

Which half of the earth should we give up?

According to Jose Montoya of France’s Station for Theoretical and Experimental Ecology, “The key thing is to protect the right areas.” His concern is that nations will allocate their least-valuable areas. “If we merely protect a proportion of the territory, governments will likely protect what’s easy, and that’s usually areas of low biodiversity and ecosystem service provision.”Baillie and Zhang don’t consider this possibility to be a deal-breaker so long as we hit the proposed targets.

The authors’ focus now is on a meeting of world governments at 2020’s Convention on Biological Diversity in Beijing. They don’t underestimate the difficulty in gaining global support for their goals, but they also see us as having little choice. As they write, “This will be extremely challenging, but it is possible, and anything less will likely result in a major extinction crisis and jeopardize the health and wellbeing of future generations.”