Why you can’t judge a dog by its breed

![a photo of a [dog breed] on a pink background.](https://bigthink.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/dog2.jpg?w=480&h=270&crop=1)

- Dozens of scientists made use of a large database of dog genetics to study whether breed is linked to behavior.

- They found only a paltry association, suggesting that breed has little influence on an individual dog’s behavior. Environment, genetics, and upbringing play larger roles.

- The study’s findings call into question laws that target specific breeds as inherently dangerous, and other breed-specific rules.

Just like you can’t judge a book by its cover, you can’t judge a dog by its breed. A canine’s behavior is far more influenced by environment and upbringing, according to a 2022 study published in the journal Science.

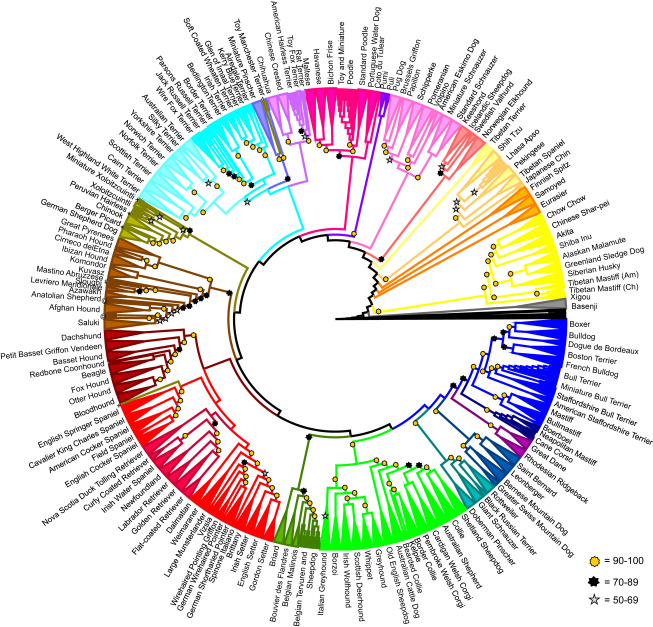

The finding comes courtesy of a Herculean effort by researchers associated with The Broad Institute at Harvard and MIT, the University of Massachusetts, and Arizona State University. Lead author Kathleen Morrill, a PhD student studying the genomics of behavior in dogs, and her numerous co-researchers surveyed owners of 18,385 purebred and mixed-breed dogs and genotyped 2,155 dogs as part of the citizen science project Darwin’s Ark.

For the project, participants were given a battery of surveys to fill out about their dogs. They then received a DNA kit to swab their pup’s saliva and send it back to the lab for genetic testing. The information was collated into a large database that was freely shared with researchers around the world. In return, curious dog owners were sent a genetic and breed profile of their dogs.

(Full disclosure: My wife and I participated in Darwin’s Ark with our mixed-breed rescue pup, Okabena. The genetic results we received scientifically confirmed that she is the cutest puppy in the whole world.)

With the copious data provided to them by citizen scientists, Morrill and her team discerned a number of fascinating findings, but the biggest was this: “Breed offers little predictive value for individuals, explaining just 9% of variation in behavior.”

In other words, a breed is far more defined by how a dog looks, and has little to do with how an individual dog behaves. “Although breed may affect the likelihood of a particular behavior to occur, breed alone is not, contrary to popular belief, informative enough to predict an individual’s disposition,” the authors wrote.

The researchers broke down dog behavior into eight categories: comfort level around humans, ease of stimulation or excitement, affinity toward toys, response to human training, how easily the dog is provoked by a frightening stimulus, comfort level around other dogs, engagement with the environment, and desire to be close to humans.

Of these behavioral traits, response to human training (also known as biddability) and toy affinity were most linked with breed, but the associations were slight. Biddability was very common among Border Collies and Australian Shepherds, while toy affinity was common among Border Collies and German Shepherds.

A dog’s age was a much better predictor of behavior. Older dogs, for example, were less excitable and less toy-driven than younger pups.

Modern dog breeds really only go back about 160 years, “a blink in evolutionary history compared with the origin of dogs more than 10,000 years ago,” the researchers described. So it makes sense that breed wouldn’t explain a dog’s behavior to a significant degree.

Hunting through the thousands of canine genomes on file, the researchers found eleven genetic regions associated with various behaviors, ranging from howling frequency to human sociability. Genes in these regions varied widely within breeds, providing further evidence that breed is only marginally linked to behavior.

The study’s findings call into question laws that target specific, supposedly “dangerous,” breeds. More than 900 cities in the U.S. currently have some form of breed-specific legislation.