Ancestry tests are “genetic astrology.” We must re-learn everything we know about DNA and cells

- There’s immense allure to imagining connections to such remote peoples, places, and times, but ancestry tests are largely “genetic astrology.”

- If you go back far enough — and “far enough” isn’t all that long ago in human history — we’re all related to each other.

- Our genes aren’t our identity, regardless of what the DNA testing companies say.

Genes are needed in development and tissue maintenance, but from the laying out of the body plan to the organization and functioning of our nervous system, cells rule their expression and make us who and what we are.

Throughout the 20th century and continuing to the present day, the common assumption has been that our identity is tightly linked to our DNA. While there’s some truth here — as Shakespeare said, “What’s past is prologue” — when it comes to development, cells and genes have very different relationships with history. It is therefore worth pausing for a moment to recap briefly the reasons behind the dominant view of the genome as the master of our being.

This view lies in the essence of DNA, those strings of Gs, Cs, As, and Ts that configure the hardware store catalogue that is your genome. This catalogue has been updated over millions of years and is unique to each of us, not in its repertoire of tools and materials but in their colors and design details. It is through these subtle differences that, in the same manner you can follow the transformation of the clumsy computers of the 1950s into your iPhone, you can trace history in your genome, a history based on the relatedness of the differences and similarities of the script. Add some historical narrative to these genetic relationships — genealogies — and you will have ancestries, lineages that, so you are told, link you to remote people and places and, if you go back far enough, link all people to each other.

We humans feel a great need to belong, to know our origins, and because we’ve been fixated on genes over the past hundred years, we’ve been using the language of genetics to write our stories. The big hitters in commercial DNA testing, Ancestry.com and 23andMe, together maintain the genomes of more than 30 million people in their books. Based on these data, you might be told you’re 37% Western Bantu, 27% Germanic, 26% Scottish, and 10% Nigerian, give or take 10 to 20%, or that 2% of your DNA is Neanderthal (as it is, on average, for all people living today, because of how humans evolved). Some companies claim the ability to compare your DNA to that of, say, Vikings, ancient Egyptians, Chumash Indians, and other populations who lived a few thousand years ago. To be descended from a pharaoh!

There’s immense allure to imagining connections to such remote peoples, places, and times. But as the organization Sense About Science says of such claims, “They are little more than genetic astrology.” Geneticist Adam Rutherford has also rightly pointed out that if you go back far enough — and “far enough” isn’t all that long ago in human history — we’re all related to each other. This is a fact. The tools and fixtures in the genome are what we need to be an animal, a primate, a human, so it’s not very remarkable that there’s so much overlap.

Genetic ancestries can be quantified, saying that we are 50% this or 25% that, but what do these numbers really mean? Do these numbers say anything about who we are today? A history of our species may be carried in our genome, but our genome does not make us who and what we are.

Just after gastrulation, the process that lays down the blueprint of an organism, we look very similar to a chicken, fish, and frog.

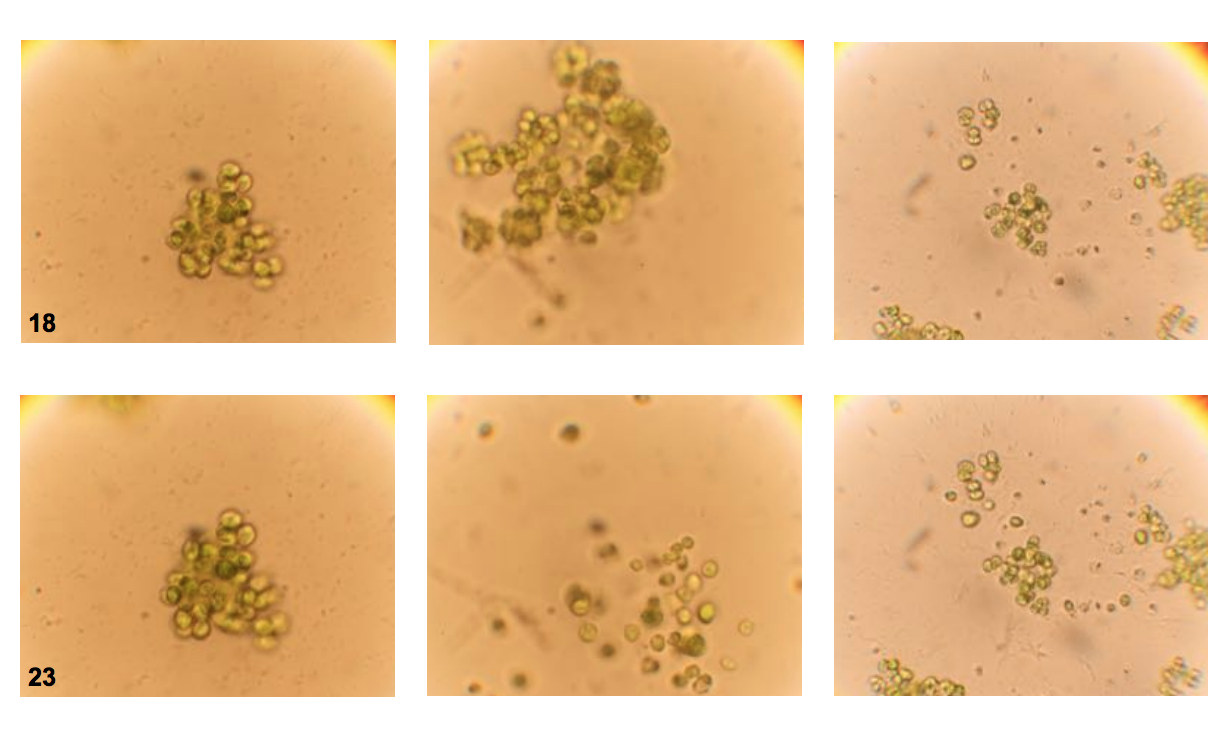

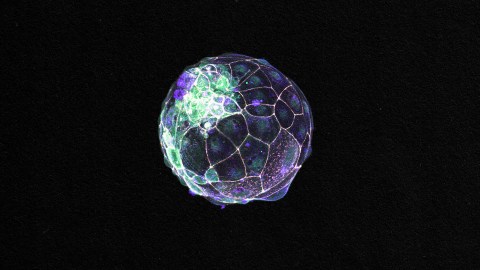

An equally interesting view of human history is contained in the story of how our cells create us, division by division, starting from the zygote’s very first division and building differences along the way. Recall the feature of embryonic development first noticed by Karl Ernst von Baer: that, just after gastrulation, the process that lays down the blueprint of an organism, we look very similar to a chicken, fish, and frog. The similarities in animal embryos connect us to the first multicellular organisms. Eukaryotic cells — those with a “true,” or well-formed, nucleus — began to use the genome in novel ways, controlling genes so that they could come together to build a robust, efficient organism that could conquer the planet.

To achieve this, cells found a handful of approaches that worked well, such as a bilaterian body plan (mirrored left and right sides) and gastrulation. Across all animals, cells draw upon the same set of tools and fixtures to lay the foundation for the body. Then, after gastrulation, they go their separate ways, building species-specific features and unique, individual beings, based on their interactions with each other and, because we’re mammals, our intercellular connections to our mother. The process of building does not end at birth; it continues throughout our lifetimes, so long as our stem cells generate new cells to keep our bodies running in good form.

Our genes aren’t our identity, no matter what the DNA testing companies say in their advertising campaigns. Indeed, these companies use the DNA from people’s tests to research how diseases caused by a single genetic mutation might be treated. In other words, they know that genes are tools, and they’re looking for ways to capitalize on the fact that these tools can sometimes be repaired.