The relatively unknown artists who produced masterpieces

- The global art world, ruled by Western institutions, is historically biased toward European and American art.

- While tides are shifting, there are many international artists that have yet to be given their due.

- Gerard Sekoto, Amrita Sher-Gil, and Camilo Egas deserve to be studied in the same capacity as Andy Warhol or Pablo Picasso.

Gerard Sekoto. Amrita Sher-Gil. Camilo Egas. Unless you studied art history or live in South Africa, India, or Ecuador, chances are you have not heard of these painters. That is unfortunate, because they were as trend-setting and forward-thinking as Pablo Picasso or Andy Warhol, two other artists from the same time period who are much more well-known.

Often, an artist’s renown says less about the quality of their work than it does about the society that prices and exhibits that work. Picasso and Warhol are omnipresent not only because they were talented but also because the international art market — dominated by Western institutions and individuals — has historically shown the most interest in art from Europe and the U.S.

While this bias is disappearing, there are many non-Western artists who have yet to receive their due. Whereas the legacies of Picasso, Warhol, Henri Matisse, Jackson Pollock, and Vincent van Gogh are constantly assessed in mainstream media, discussions of Sekoto, Sher-Gil, and Egas — to use them as examples — remain mostly limited to obscure scholarly articles and excerpts from museum catalogs.

Art and apartheid

Painter and pianist Gerard Sekoto was born in Transvaal, South Africa in 1913. Remembered as a pioneer of South African art as well as one of the fathers of Black contemporary art in general, he became the first Black artist in South Africa to sell to a museum when the Johannesburg Art Gallery purchased his painting Yellow Houses — a Street in Sophiatown in 1940.

Fatefully, Sekoto’s artistic career coincided with the institutionalization of apartheid. Sophiatown, the Johannesburg suburb where Sekoto lived when he organized his first exhibitions, served as a center for Black art, culture, and politics until its residents were forcibly relocated to segregated neighborhoods by the all-White South African Nationalist Party in 1950.

As Julie McGee notes in her review of N. Chabani Manganyi’s biography of Gerard Sekoto, Black South African artists are often studied in a political rather than an artistic context. In other words, critics, curators, and scholars approach their paintings not just as works of art, but as political statements and expressions of ethnic identity.

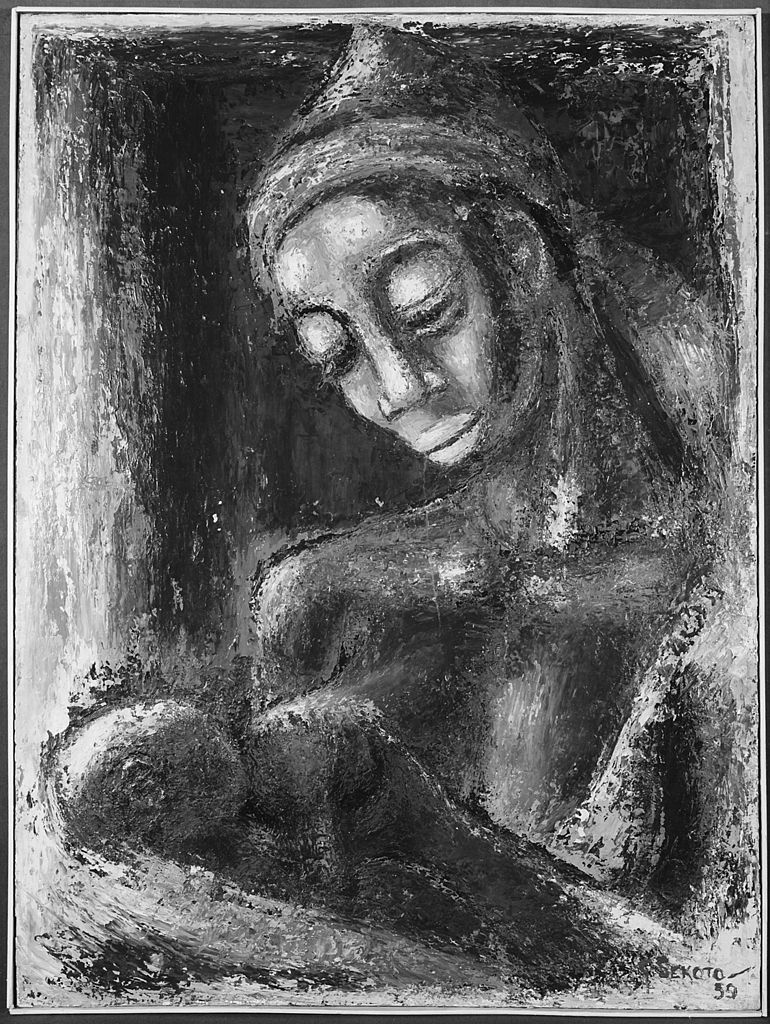

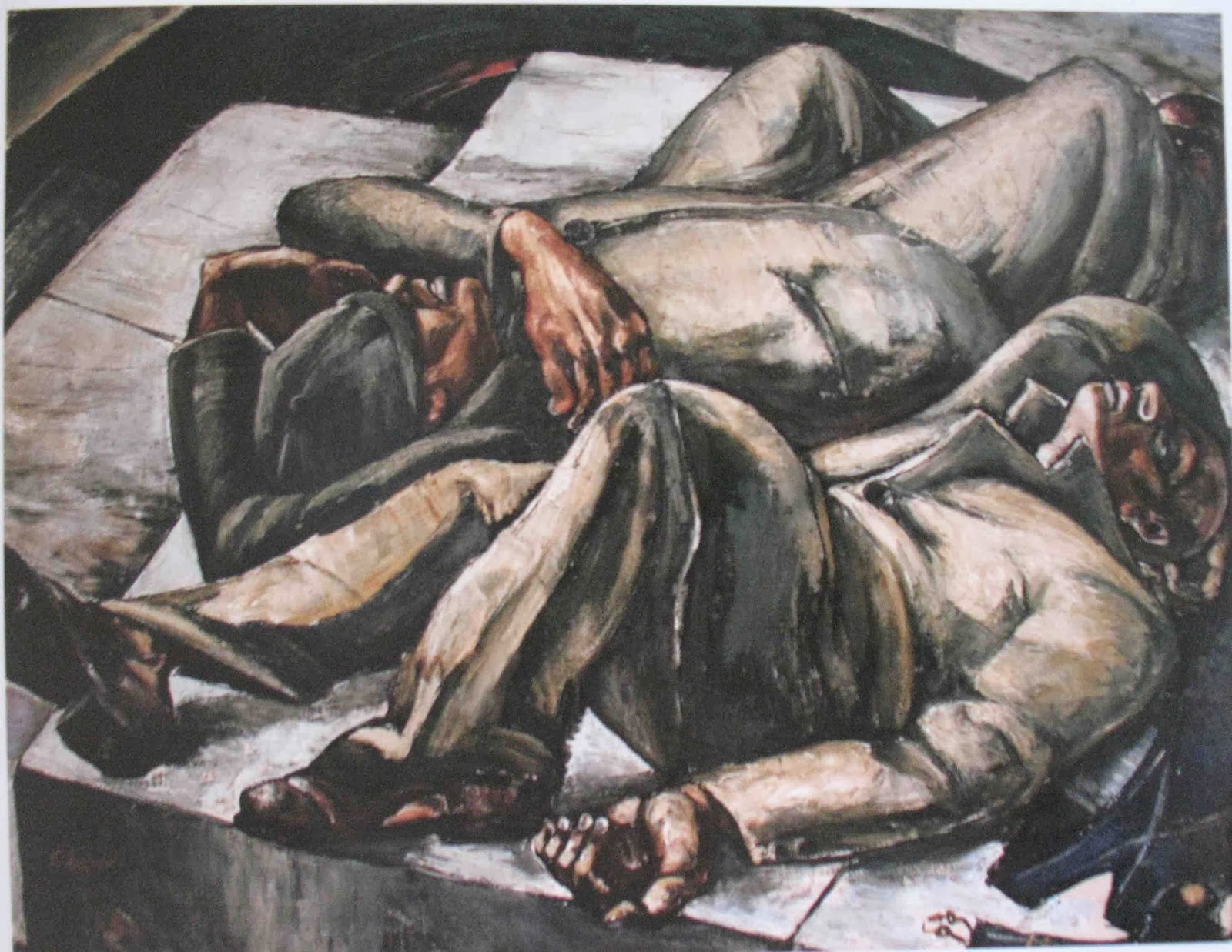

Sekoto’s oeuvre does not easily fit into this mold. While some paintings like Prisoners Carrying a Boulder (1945) or Song of the Pick (1947) contain elements of Resistance Art, they aren’t as overtly political as the paintings of other artists they inspired. Gerard Sekoto was, first and foremost, a painter. He didn’t use his brush as a pen, but as a brush — a tool that can capture the essence of reality better than a camera.

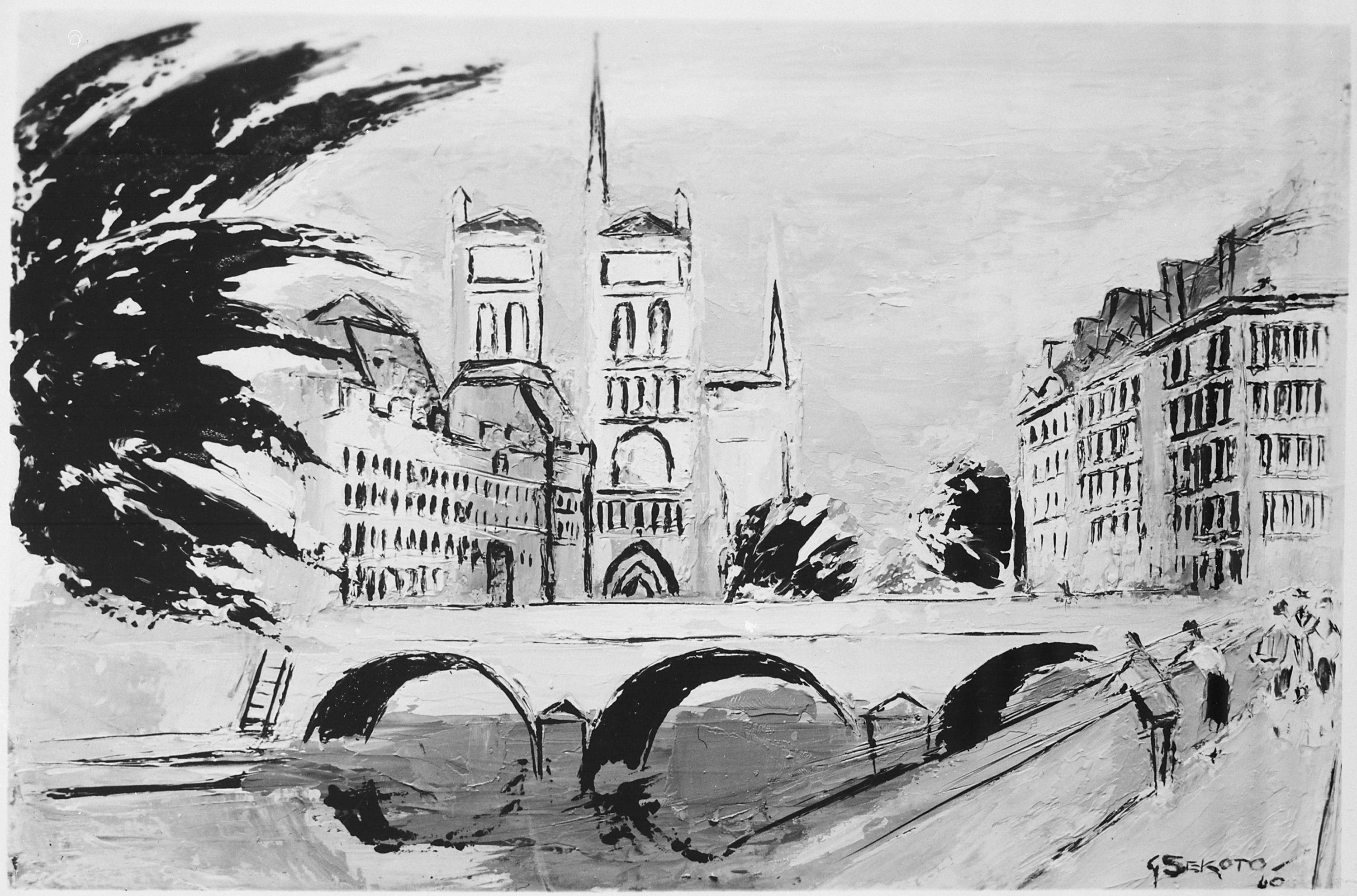

In 1947, Sekoto left South Africa for France. While his home country mourned the loss of one of their best artists, Sekoto found work as a pianist, wrote and published musical compositions, and dove deeper into his studies of line, form, shape, and color, using his newfound knowledge to represent Black subjects and experiences in Paris.

Painting women’s bodies

Amrita Sher-Gil lived a regrettably short life, dying at age 28 under unknown circumstances. The daughter of a Sikh aristocrat and a Hungarian opera singer, she was born in Budapest in 1913 — the same year as Sekoto — and studied painting at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where she encountered the work of Paul Cézanne and Amedeo Modigliani.

Sher-Gil credited these modernist painters — who were themselves inspired by traditional art from Africa and Asia — for helping her understand and appreciate painting and sculpture from India, a country she had visited sporadically during her childhood and was eager to move to after she completed her art education. It was there, she thought, that her future as a great painter awaited.

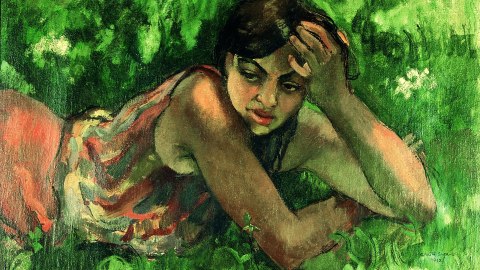

In India, Sher-Gil became known for her depictions of women’s bodies. “Unlike usual depictions in India,” Elena Martinique discusses in an article for Widewalls, “where women were cast happy and obedient, her subtly expressive representations conveyed a sense of silent resolve. A female body characterized by a passive sexuality emerged as one of her favorite subjects.”

Indian art critics of the early 20th century interpreted paintings through a Hindu lens. Their essays mention “aesthetic emotion” and “hypnosis.” They echo the Russian writer Leo Tolstoy in his belief that art should be experienced rather than analyzed, and that a work of art can be considered “good” if it communicates its message in a manner that is largely instinctive.

Sher-Gil followed the same philosophy. Like Sekoto, she used abstraction to intensify the mood and emotion of a scene. “Good art always tends towards simplification,” she is quoted in GHR Tillotson’s article “A Painter of Concern: Critical Writings on Amrita Sher-Gil,” adding that form is never imitated and that it can only be interpreted by the artist, which is another way of saying that abstraction can do a better job at capturing the essence of a subject than straightforward representation.

Indigenismo

Camilo Egas, born in Quito’s San Blas neighborhood in 1889, learned to paint in a time when the Ecuadorian government sought to Westernize the country by pressuring art schools into teaching Neoclassicism and hiring European teachers. These efforts had the opposite effect, as painters such as Paul Bar and Luigi Casadio encouraged students to incorporate their unique heritage into their work.

Thus, the Western-inspired or Costumbrista style gave way to Indigenismo, a movement characterized by a renewed interest in pre-Colombian art and the relationship between the state and Indigenous minorities. Egas emerged as an early champion of Indigenismo, drawing on his studies in Ecuador, Spain, and France to introduce the movement to a global audience.

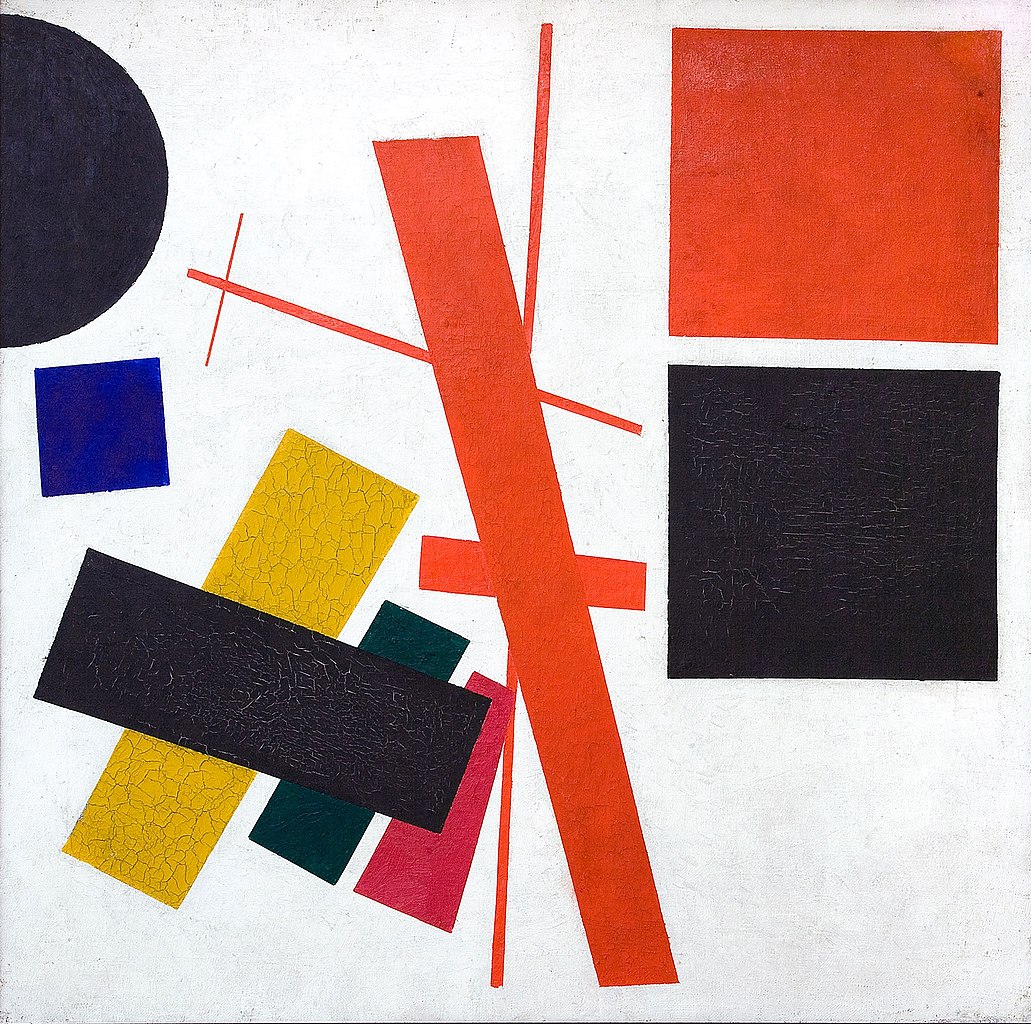

It’s no accident that rise of Indigenismo corresponded with the rise of Marxist parties and guerilla groups in South America. Some of Egas’ paintings are vaguely reminiscent of the Socialist Realism produced under Joseph Stalin in Russia: They walk the line between abstraction and representation, are extremely colorful, and somewhat idealized their depiction of Indigenous peoples.

Some argue that this idealization borders on discrimination. An article by Juan Cabrera distinguishes between South American artists that depict Indigenous people inclusively, as subjects, and those that depict them exclusively, as objects. Egas is placed in the second group. Others disagree, finding Egas’ approach sympathetic.

This kind of ambiguity — the idea that multiple conflicting interpretations can be true at the same time — is not just present in the work of Camilo Egas but in that of Amrita Sher-Gil and Gerard Sekoto as well. It explains why their work has made such a profound impact on the people that have taken the time and effort to become acquainted with them.