“Eucatastrophe”: Tolkien on the secret to a good fairy tale

- In Greek mythology, the story of Pandora’s box comes in (at least) two versions. In one, hope is released as the final evil in the world. In another, hope is the only consolation and weapon we have.

- J.R.R. Tolkien coined the word “eucatastrophe” to describe a hallmark of good fairy tales: Good people win out despite the odds. Hope, in other words, is a vital story component.

- For Tolkien and the Christian existentialist Gabriel Marcel, hope is the most important disposition we can possess. Without it, the darkness of the world will win out.

There are at least two versions of the story of Pandora’s box. In the classic version from the Greek poet Hesiod, when Pandora’s curiosity got the better of her, she unleashed into the world all sorts of evils: sickness, famine, death, and people who ask questions at the end of a meeting. When Pandora finally closed the jar, she left only one “evil” inside: hope. For Hesiod, there’s nothing so cruel as hope. Hope is what forces us to carry on building, fixing, and loving when the world offers only destruction, chaos, and heartbreak. It’s what gets us off the ground only to be punched back down. Hope is the naivety of a fool. As Friedrich Nietzsche put it, “Hope, in reality, is the worst of all evils because it prolongs the torments of man.”

Another variation of the Pandora’s box story is a Greek fable called “Zeus and the Jar of Good Things.” In this account, everything is inverted. The jar does not contain misery but good things. When “mankind” (there’s no Pandora in this version) opened the jar, they let out and lost all these good things: the things that would have made life a paradise. When the lid was closed, there was only one divine blessing left: “Hope alone is still found among the people.”

The author J.R.R. Tolkien and the Christian existentialist Gabriel Marcel would likely prefer the second version. After all, they considered hope to be perhaps the most important part of being human.

The eucatastrophe

Kurt Vonnegut is famous for writing novels like Slaughterhouse-Five and Cat’s Cradle. In storytelling circles, he’s famous for his “shapes of stories.” These were eight diagrams that define the traditional arcs of common stories, like “Boy Meets Girl” or “From Bad to Worse.” His arc about fairy tales goes like this: Things start badly and then get a bit better. But then there’s a catastrophe that brings everything to ruin. The story ends with a drastic upheaval in fortunes — a transformation and magical finale — and everyone lives happily ever after.

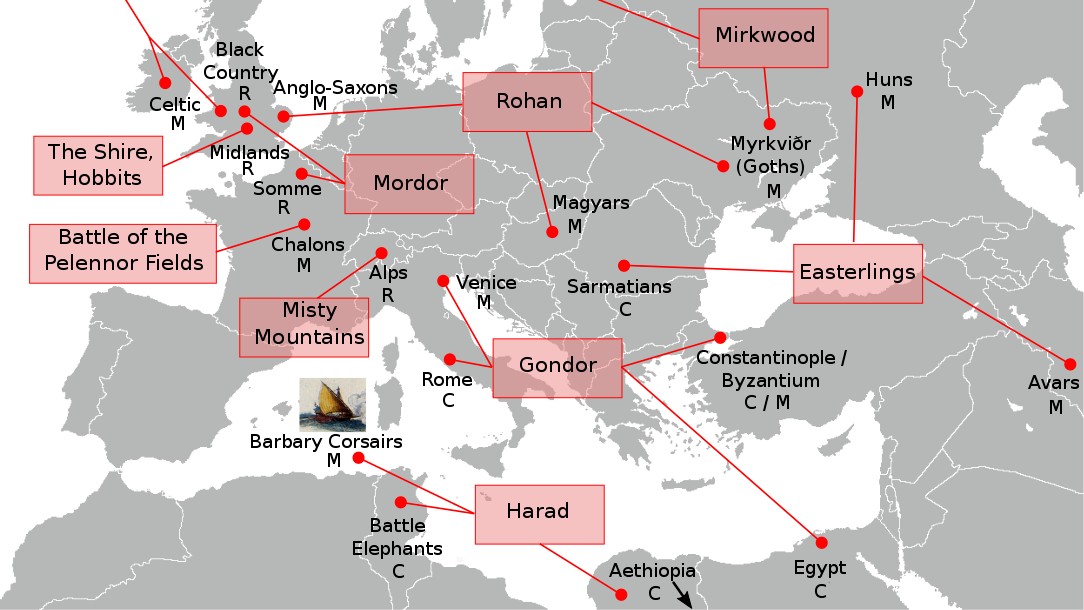

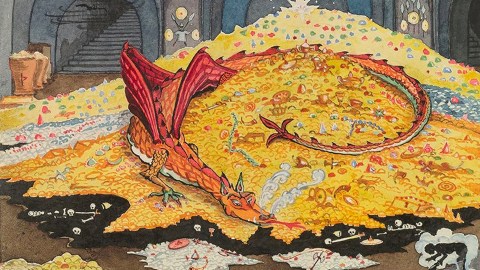

Tolkien, were he alive, would agree. For him, the single most important element of a fairy tale is this final dramatic reversal of misfortune. He coined the word “eucatastrophe” to describe it. “The consolation of fairy-stories [is] the joy of the happy ending: or more correctly of the good catastrophe, the sudden joyous ‘turn,'” Tolkien wrote. The Lord of the Rings does not end with the hobbits dead and Sauron cackling over his orcish, industrial empire. It ends with light beating dark — with simple kindness, love, and companionship winning out over evil.

Lifting the heart

Tolkien is very careful to make the point that this is not some form of escapism. It’s not quixotic wish fulfillment. It does not pretend the world is an endlessly happy idyll of singing dwarves and affable wizards. The world has great suffering and misery, and there are plenty of nightmares to be found. The eucatastrophe, though, is “the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat.”

The purpose of a good fairy story is not to hide the shadows of the world. The original Grimms’ Fairy Tales (not the sanitized Disney versions) were full of infanticide, cannibalism, and horror. The mark of a good fairy story, Tolkien wrote, “…[is that] however fantastic or terrible the adventures, it can give to child or man that hears it, when the “turn” comes, a catch of the breath, a beat and lifting of the heart, near to (or indeed accompanied by) tears.”

Hope is all we have

The religious undertones here are not accidental. Tolkien was a Catholic who was fond of the redemption and grace found in the narratives of the Bible. Marcel did not, as far as we know, read Tolkien, but his own philosophy of hope bears striking similarities.

What Tolkien describes as the eucatastrophe, or final deliverance, Marcel called hope. For Marcel, “Hope consists in asserting that there is at the heart of being, beyond all data, beyond all inventories, and all calculations, a mysterious principle which is in connivance with me.”

Hope is the belief in an order to the Universe — an order where everything will turn out well enough. It is a kind of faith that simply refuses to accept that things are broken, or that misery, suffering, and death are all that exist. Marcel was a Christian, but his account of hope can apply to anyone. The hopeful of the world are those who see the Universe as being on their side. Set against “all experience, all probability, all statistics,” they see that a “given order shall be re-established.” Hope is not a wish. It is not optimism or naivety. It is an assertion. It is telling the world, “No, this is not the way things will be; things will be better.” For both Marcel and Tolkien, it is only with hope that we banish despair.

You do not haggle with or beg the darkness. Like a blazing torch, you must shine hope brightly and fiercely.