Existential hope: How we can embrace deep time and create the brightest of futures

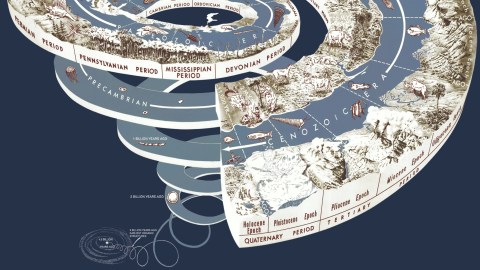

Credit: U.S. Geological Survey / Public domain / Wikimedia Commons

- We can navigate an uncertain future with a collective sense of agency, argues Richard Fisher.

- Over generational timescales, radical changes for the better are possible.

- Long-term thinking can steer us toward a “deep civilization.”

When I talk or write about the long term — particularly the deep future — I sometimes encounter a form of resigned nihilism, expressed as: “That’s all very well, but we’ll all be gone.” In some circles, it has become almost fashionable to quip that the apocalypse is nigh. In that context, it becomes something of a trap to talk about the long view: you’re either seen as far too optimistic or callously unconcerned with today’s problems. Too much pessimism, though, can lead to doomism — a perspective that remains locked in the present, mired in apathy, helplessness or anger.

It’s undeniable that there are severe dangers ahead for the world. However, I would prefer to navigate those futures equipped with the belief that I and those around me have agency. I do not believe I can steer a path alone — it is a collective, cross-generational enterprise — nor do I know how tomorrow’s events will play out. But I would rather operate under the belief that I can do something rather than nothing. Surprisingly, most of the scholars I have met who actually study the end of the world are not doomist at all. They might spend their days contemplating catastrophe, but they believe that a long-term perspective is necessary to avoid that fate, and are often motivated by the prospect of future flourishing.

The blinkered norms of our age hide so much from us. What we mustn’t do is let them hide the possibility that things can improve as well as worsen. When past generations faced gross inequalities, the fog of conflict, or great injustices, it would have felt overwhelming at times — but over generational timescales, changes for the better are not impossible, and in this we can find a source of energy and determination.

There’s a term used by some long-term thinkers that I believe deserves to be known more widely: existential hope. This is the opposite of existential catastrophe: It’s the idea that there could be radical turns for the better, so long as we commit to bringing them to reality. Existential hope is not about escapism, utopias or pipe dreams, but about preparing the ground: making sure that opportunities for a better world don’t pass us by. So, if taking the long view demands anything of us, it is this: a commitment to seeking and cultivating hope when all feels bleak. This may well prove to be the grandest challenge of our time, but it is what we owe to our predecessors and our descendants.

Over the long term, I believe it is within humanity’s potential to build towards what I call a deep civilization. If a time-blinkered society is one that cannot escape the present moment, a deep civilization is one that has a richer sense of its roots, and its trajectory into tomorrow.

Journalists and communicators provide temporal context and depth, rather than outrage and noise.

In a deep civilization, businesses are not swayed by short-term individualist profits, but are motivated by ethical and sustainable goals. Politicians have the foresight and wisdom to support policies that benefit all people and living creatures in all times, not just their own voter base. Journalists and communicators provide temporal context and depth, rather than outrage and noise. Technologists and designers aim to foster cross-generational connection, not anger and division. And every citizen knows that they are each a link in a chain that stretches across the generations, with the collective capability to improve the world for their children. They are, to quote the scientist Jonas Salk, “good ancestors.”

At the same time, each member of this deep civilization is keenly aware that their evolution is incomplete — that the societies and communities they are building are just one step on the way towards what they have the potential to become. They pass that hope across generations with the promise of a world that could be more just, wiser and more enlightened. Across the very long term, there could be whole new heights for our species that we have yet to explore. As the philosopher Toby Ord has argued, our present may be marred by suffering and unsustainable practices but we should aspire to more than ridding these problems. “A world without agony and injustice is just a lower bound on how good life could be. Neither the sciences nor humanities have yet found any upper bound,” he writes. “We get some hint at what is possible during life’s best moments: glimpses of raw joy, luminous beauty, soaring love. Moments when we are truly awake. These moments, however brief, point to possible depths of flourishing far beyond the status quo, and far beyond our current comprehension.”

Such talk of a grander future may sound utopian and out of reach — but it is not impossible, so long as we make the right choices today. One reason it is so difficult to see how things could be so different is a psychological effect called the “end of history” illusion, which describes how people struggle to imagine how they might change later in their lives.

While people accept that they have changed significantly since they were children, they assume that their present self is how they will always be. This can be a collective illusion too, hiding from us how much our societies still stand to evolve.

As a social species, we build on the minds and experiences of others — past and present.

Are we ready to become a deep civilization? Not yet. There is still a long way to go before we fully understand and accept the relationships between the human lifespan, past and future generations, and the long-term timescales of Earth and the natural world. And for the foreseeable future, deep time may continue to feel daunting and intractable for many: a “delightful horror” that feels too big to imagine with our current mental faculties. Humanity, though, is nothing if not flexible: throughout our evolution we have adapted and expanded our perspective to embrace all sorts of abstract and complex concepts that exist outside direct experience and memory: morality, peace, charity, freedom, and law — to name but a few. Across history, we have encountered ever-more complex ideas, and learned ways to break them down into terms and concepts that we could understand.

Crucially, when we seek the long view, we do not do so alone. As a social species, we build on the minds and experiences of others — past and present. And through this cooperation, an individual can unlock insights that they cannot see, hear, or feel themselves.

So, the coming years could mark a turning point in our temporal evolution. On one path, we destroy our species because we failed to think long term; on the other, we flourish into a future extending millions of years hence. If we are to thrive beyond the next century, we must transform our relationship with time — to close the gap between the salient experience of the present moment and the far brighter trajectories that could lie ahead.