Why 1972’s “The Other” is a forgotten classic of American horror films

- In 1972, a popular psychological horror novel called “The Other” was adapted into a Hollywood movie.

- The film flopped at the box office and is difficult to find today.

- Despite its obscurity, “The Other” remains a classic of American horror films, in part because its creators didn’t start out trying to make a horror film at all.

In 1971, a down-on-his-luck Hollywood actor named Tom Tryon saw his fortunes change with the smash success of his psychological thriller novel, The Other. The story was quickly adapted into one of the most terrifying Hollywood horror films of the 1970s. But despite the initial popularity of the book, the film version of The Other has all but vanished from the public imagination today.

The Other unravels over the summer of 1935 on a farm in the fictional New England community of Pequot Landing. Told from the perspective of two identical twin boys, Niles and Holland Perry, the story centers on a strange, supernatural power bestowed to the twins by their mystical Russian grandmother. The power, called “the game,” is a form of astral projection that allows the boys to view events through the eyes of individuals around them.

Niles likes to play the game for fun. But Holland uses the power to more devious ends, reflecting the psychological impacts of family turmoil around them and their grandmother’s well-intentioned but excessive maternal instinct. Soon enough, folks in the community start suffering terrible fates: Men crushed by apple cellar doors, children impaled by pitchforks, and newborn babies vanishing during nightly thunderstorms.

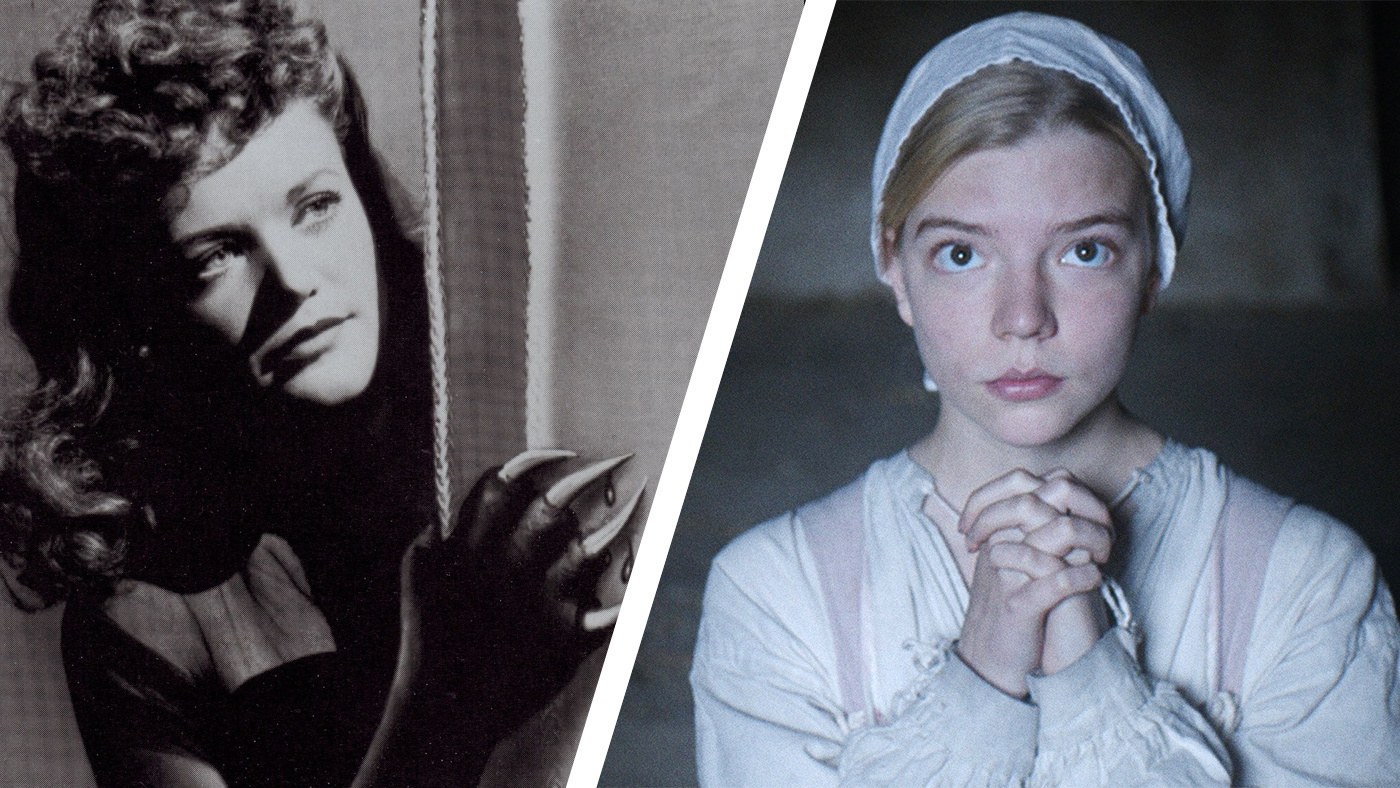

One aspect of The Other that makes it a remarkable horror film is its unique use of a common archetype in the genre: the (seemingly) innocent child. Children often represent a battleground on which forces of good and evil struggle, speaking to the fundamental corruptibility of human nature. In The Other, this archetype plays out between two identical twins, one of whom is decidedly less inclined toward forces of good.

Although the film might suggest that one of the boys represents evil and the other good, things turn out to be not quite as morally or psychologically simple. It is a cleverly deceitful film. That’s partly because, at first, The Other doesn’t really seem much like a horror film at all. In fact, it started out as a Gothic drama and didn’t really lean into horror until post-production.

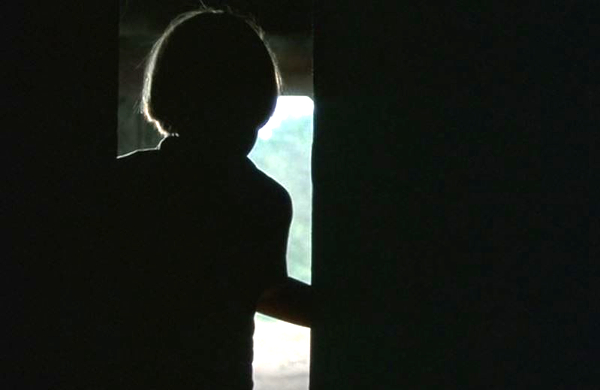

You can see this through The Other’s permeating sense of nostalgia, which is both alluring and, inevitably, unnerving. Shots are imbued with gold tones, and much of the film seems like an atmospheric daydream, back to a time when American life wasn’t quite easy but at least was simpler, as exemplified through the unsupervised, boys-will-be-boys shenanigans of Niles and Holland.

Director Robert Mulligan said this was an intentional decision.

“I want to put the audience into the body of the boy with this shot and to make the experience of the film, from beginning to end, a totally subjective one.”

In one of the most visually imaginative sequences of the movie, Niles plays “the game” to get inside the mind of a black bird perched on a fence. The camera takes the perspective of the bird as it soars over Pequot Landing. We listen to Jerry Goldsmith’s lovely score, as it romanticizes the beauty of the moment — and then, for some unexplained reason, the score starts hitting evil-sounding notes upon glancing at the sharp prongs of a nearby pitchfork. Concealed beneath the film’s heavenly fabric is an undercurrent of deadliness and danger.

Like nostalgia itself, it is a mistake to fully trust the perspectives of Niles and Holland. The film ends up being terrifying not for the evil imagery, but for the creeping realization that, underneath the sunshine and superficial pleasures, something darker is brewing — maybe it was there all along.

A popular book becomes a flop at the box office

Director Robert Mulligan, who also directed 1962’s To Kill A Mockingbird, initially set out to make a film with Hitchcockian suspense elements, and Tryon’s story gave Mulligan the tools to make both a moving and suspenseful picture about a loving yet troubled rural family. However, test screenings yielded complaints from audiences that the film was too slow, so Mulligan and his editor, O. Nicholas Brown, ruthlessly cut the film down, until what lingered the most about the final cut were the gruesome details.

The end result was arguably one of Mulligan’s best and most thought-provoking films. Still, The Other died at the box office, and Tryon — who wrote the screenplay and served as executive producer — was displeased, dismissing the film as “badly cut and faultily directed.” While making a YouTube video essay about the production of The Other, it was interesting to hear differing viewpoints from the film’s surviving cast and crew.

Some of them believed that it was a mistake to edit it as a horror film — that it wasn’t quite as immersive as the book. One of the child actors told me that he was disturbed by the film’s violence, and that he didn’t fully appreciate the filming experience until adulthood.

A half-century after its release, The Other is frustratingly hard to locate and watch today, unless your local library carries a DVD copy. I recommend getting the Twilight Time Blu-Ray, if you can find a used copy on eBay; it’s got the fantastic bonus feature of the isolated Jerry Goldsmith score, which is so hauntingly perfect for the Halloween season, you really ought to rip it to iTunes. At the same time, I fear that because of Disney’s recent acquisition of Twentieth Century Fox, The Other has become lost in the shuffle of their studiolibrary. As of this writing, you can’t even rent it digitally on Amazon.

This film scares me like nothing else that I’ve seen. I look at its depiction of children spending their summers playing at old, wooden houses in the rural countryside, and certain memories both happy and bittersweet come flooding back to me. But The Other is also about how our nostalgia for the innocence of childhood can be deceptive. It says that there is a Niles and a Holland Perry in all of us.