Tatlin’s Tower and the untapped potential of early Soviet architecture

- In order to solidify his rule, Vladimir Lenin ordered the production of futuristic monuments that could help Russia redefine its national identity.

- The architect Vladimir Tatlin came up with a design for a 400-meter-tall tower that would have housed key government branches and other organizations.

- If built, the Tower would have qualified as a modern world wonder. Unfortunately, an overambitious design prevented it from ever coming into existence.

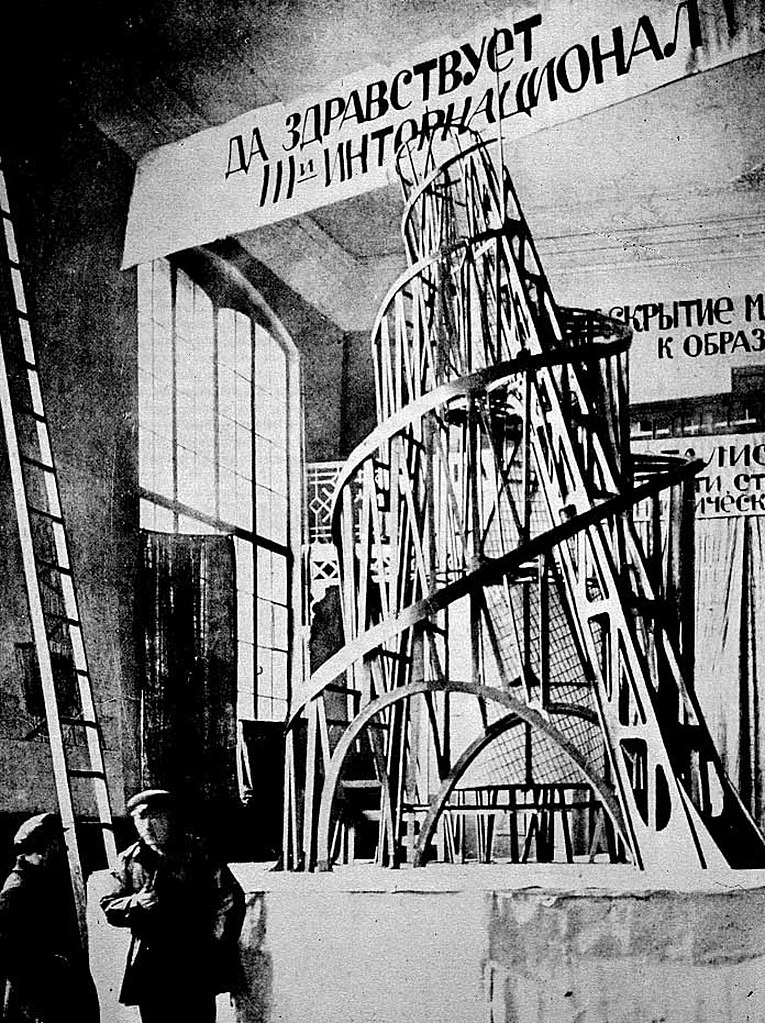

In 1920, the Russian architect Vladimir Tatlin proudly unveiled the very first wooden model for the Monument to the Third International. The building, which would function as the new and improved headquarters of the Comintern, was planned to be built in the city of Petrograd, today’s Saint Petersburg. Communist Party officials who came to review it offered mixed opinions. Leon Trotsky said Tatlin’s Tower, which would have dwarfed the Eiffel Tower in size, was “impractical and romantic.” His accomplices, Vladimir Lenin and Anatoly Lunacharsky, were a bit more enthusiastic; before them stood a visual representation of the communist utopia they were trying to create.

In order to appreciate the boldness of Tatlin’s design, one must first understand its historical context. Three years earlier, Bolshevik revolutionaries had staged a coup d’état that transformed Russia from a parliamentary democracy into a dictatorship of the proletariat. But while the country had become a one-party state, its people were far from unified. Czarist sympathizers, referred to as “Whites,” plotted to reinstall what remained of the Romanov dynasty. Other socialist organizations, sidelined by the Bolshevik takeover, resisted as well. A deadly civil war ensued, and while the Bolsheviks emerged victorious, their rule remained shaky. In order to truly win the people’s trust, they needed propaganda capable of instilling a new sense of national pride.

In order to achieve this, the Communist Party set up what historians now refer to as a program of Monumental Propaganda. Based on a series of pamphlets and speeches from Lenin, this program sought to replace memorials erected in honor of the czar with shrines devoted to Marxist-Leninist philosophy and the new form of government that had been built around it. As stated in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, a typical Soviet monument functioned as “a propaganda vehicle in the fight for victory of a new system, for enlightenment and education of the popular masses.” Tatlin was the person put in charge of this program. He was a good choice.

Tatlin began his career as a painter. He mostly painted icons for churches of the Orthodox Christian faith, but eventually grew disillusioned with religious symbolism. Frustrated by the limitations of visual artforms and eager to make something that would have a direct impact on people’s lives, he developed an interest in architecture. Along with Kazimir Malevich, another painter and the creator of the famous Black Square, Tatlin was a key figure in Russian constructivism — a forward-facing cultural movement that informed all aspects of the buildings Tatlin pitched his superiors. Of these, Tatlin’s Tower was considered the cream of the crop. Unfortunately, it was never built.

Tatlin’s Tower: Its Form and Function

Tatlin’s vision for the Monument was unlike anything the world had ever seen. With a planned height of 400 meters, the building had the shape of two intertwining helixes. These helixes cradled four distinct, suspended structures. The spaces inside had unique purposes and were given different shapes. The first space, a cube located near to the base of the structure, would have been reserved for lectures, conferences, and legislatures. Located above the cube was a pyramid that could be used for executive party meetings. Above the pyramid was a cylinder that would have housed an information center that broadcasted news, declarations, and manifestos.

If completed, Tatlin’s Tower would have been both a testament to and an expression of early Soviet ideology. The building, constructivist in its design, would have been made entirely from locally sourced, materials. Where government buildings in capitalist countries were typically adorned with marble, ivory and other expensive materials, Tatlin wanted his tower to be made using materials that were staples of Soviet industry and, as such, had special significance to the working class. These included iron, steel, and glass. In an article written for the Slavic Review, Alexei Kurbanovsky noted that the structure, like the October Revolution itself, could be interpreted as a Freudian “refutation of father-figures.”

Tatlin’s Tower was designed during a time when Communist rule was still nascent and party leaders sought to establish a new and distinctly socialist identity through art. Until this point, wrote Allison McNearney in an article for The Daily Beast, the Soviets had commemorated their past in the same way as the czars before them: through paintings and sculptures that represented a particular person or a specific event. Tatlin’s Tower was unique precisely because it was nonrepresentational. Rather than depicting a single individual, the construction addressed an entire socioeconomic class of people.

A once inspiring future

Despite minor criticisms, Tatlin’s plans for the Monument were received enthusiastically by party officials. However, as plans for its construction began to take shape, the Bolsheviks quickly realized the project was, as Trotsky had stated from the start, more than a little overambitious. So overambitious, in fact, that it could never be completed. In her book, The Russian Experiment in Art, the art historian Camilla Grey stated that post-revolutionary Russia would go bankrupt if it tried to acquire the insane amounts of steel and iron needed for the tower’s skeletal framework.

That’s not even talking about the feats of engineering that Tatlin had incorporated in his design. Remember how the tower was actually made up of four separate structures suspended in the double helixes? Well, in Tatlin’s original design, each of these would have rotated on their axes, completing a full revolution in accordance with the importance of the institutions conducting their business on the inside. The cube that contains the legislature would have completed a full rotation once per year. The pyramid above, housing the offices of party executives, would have needed a month. The information center, located at the very peak, would have rotated once a day, offering a 360-degree view of Petrograd.

Although Tatlin’s Tower never came to fruition, it still made the strong impression its creator had desired. His design is considered a staple of Russian constructivism — inspiring not only Russian designers but a whole host of modern architectural movements as well. The building’s shape has become instantly recognizable, even to people who know next to nothing about Soviet history. This is, perhaps, thanks to contemporary artists who have incorporated its image into their own work. Ai Weiwei’s statue, The Fountain of Light, on display at the Louvre in Abu Dhabi, is essentially a carbon copy of Tatlin’s Tower, albeit repurposed as a chandelier.

Ironically, one discipline the tower didn’t much influence was Soviet art. After plans for its construction got scrapped, party officials decided to go into a new direction with their country’s cultural institutions. Where pioneers of abstract music, painting, literature, and architecture had initially fought alongside the Bolsheviks in their campaign to build a new world, they would soon be persecuted by the secret police of Joseph Stalin. Under Stalin’s rule, the Soviet Union doubled down on a style called Soviet realism. Tatlin’s inspiring futurism was exchanged for conventional, representational art — work that made the reality of everyday Soviet life seem better than it really was.