The most compelling representations of Satan in world literature

- Although infamous today, the character of Satan has been reinvented many times over the course of human history.

- Generally speaking, he developed from Dante and Milton’s tragic and misguided villain into Goethe’s and Bulgakov’s sardonic antihero.

- When placed side by side, these iterations can tell us a great deal about the time of their creators.

Given how familiar we are with Satan today, it may come as a surprise to learn that the concept of the “great opposer” was not embedded in the Abrahamic religions from the very beginning. Instead, the character evolved slowly over time, his origin story becoming a mishmash of different Eurasian myths, and his relationship to God and man changing in accordance with society itself.

While some theologians argue that the snake in Eden was actually Satan, the actual text of the Book of Genesis contains no mention of his name or likeness. In the Torah, Satan makes his first explicit appearance during events of the Book of Job. Here, he appears as a loyal albeit snarky angel that was tasked with filling the human world with obstacles that forced its inhabitants to chose between good and evil.

In her book, The Origins of Satan, religious historian Elaine Pagels argues that Satan did not become a true antagonist to God until the 1st century. Looking to unite the Jewish followers of Christ during their relentless persecution at the hands of the Roman Empire, Gospel writers adopted an us-versus-them narrative that depicted their oppressors as incarnations of the Devil himself.

As the personification of evil — be it mindful or mindless — Satan soon began appearing in nonreligious writings. Placing this larger-than-life figure outside of the scriptures in which he was first introduced, these storytellers not only influenced our thoughts on the nature of sin, but also taught us a thing or two about the religious institutions that have claimed to protect us from it.

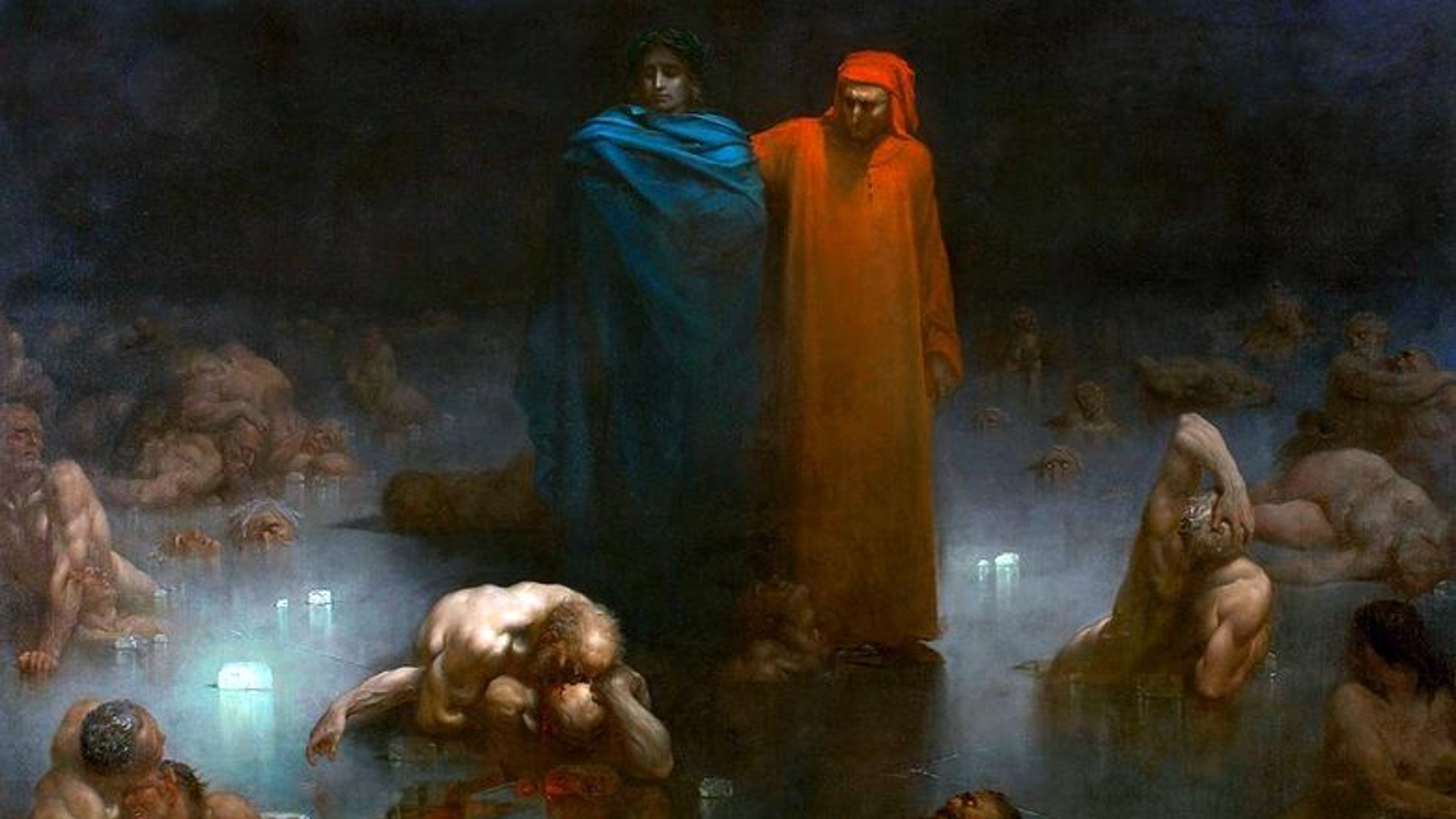

The Divine Comedy – Satan

One of the most famous depictions of Satan outside of religious texts can be found in Dante’s Divine Comedy, where he is depicted as a fearsome, three-headed beast. Entrapped in an icy lake (frozen, ironically, by the frantic flapping of his own wings), the once beautiful Angel of Light consumes the greatest traitors in Christian and Italian history: Judas Iscariot, and Brutus and Cassius, Julius Caesar’s assassins.

Located at the very center of hell, Dante’s Satan is further removed from heaven than any other being in the Divine Comedy. This is fitting, considering Dante portrays him as God’s inverse. Both, noticeably, are presented as immovable movers: beings that, like stars, attract others while they themselves remain in stasis. However, while God stays put by the power of his own volition, Satan remains stuck.

The punishment this Satan received for his rebellion against God is nothing short of poetic. The imprisoned giant, incapable of speech or thought, is a far cry from the angel which had been described in the Book of Revelation, who chose free will over servitude to God and used his cunning and charisma to start a rebellion in the court of heaven.

Not only was Satan’s rebellion unsuccessful, but it actually caused him to end up in the very situation he had wanted to avoid. Conversely, the most unsettling thing about this iteration of the character isn’t the punishment to which he has been subjected, but the sheer fact that he is rendered incapable of grasping his own terrible fate.

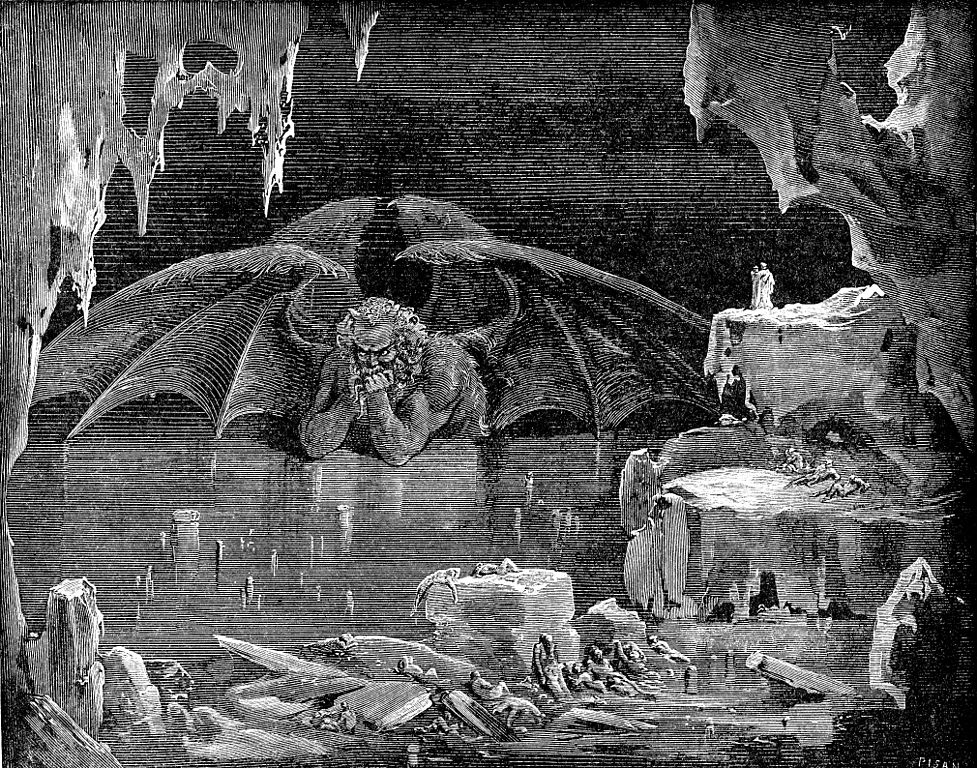

Paradise Lost – Lucifer

Lucifer, the antagonist of John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost, is often considered as one of the most striking characters in all of British literature. As far as depictions of Satan in modern media are concerned including the titularly titled Netflix show as well as series such as Breaking Bad and Peaky Blinders, Milton’s version of the character – mobile and full of personality – has proven to be far more influential.

As with Dante, Milton’s poetic genius was so great that he was essentially able to add his own chapters to a religious narrative that had been passed down for centuries. In the poem, he attempts no less than to offer an alternative version to the book of Genesis, built around the theme of “Man’s disobedience, and loss thereupon of Paradise.”

Spending considerable time and effort on developing the personal motivations behind Lucifer’s rebellion, Milton speaks concretely about things the Divine Comedy had only hinted at. Milton’s take on the character likewise wants autonomy, but this desire is made to seem all but pathological. “Better to reign in Hell,” this Lucifer famously speaks, “than to serve in Heaven.”

The Satan found in Paradise Lost became especially popular among western readers. Writing for The Atlantic, editor and literary critic Ed Simon proposed that this particular iteration had an “independent streak that appeals to the iconoclasm of some Americans.” His need for freedom, even if it would lead to chaos and suffering, perfectly matched the spirit of a developing capitalist economy.

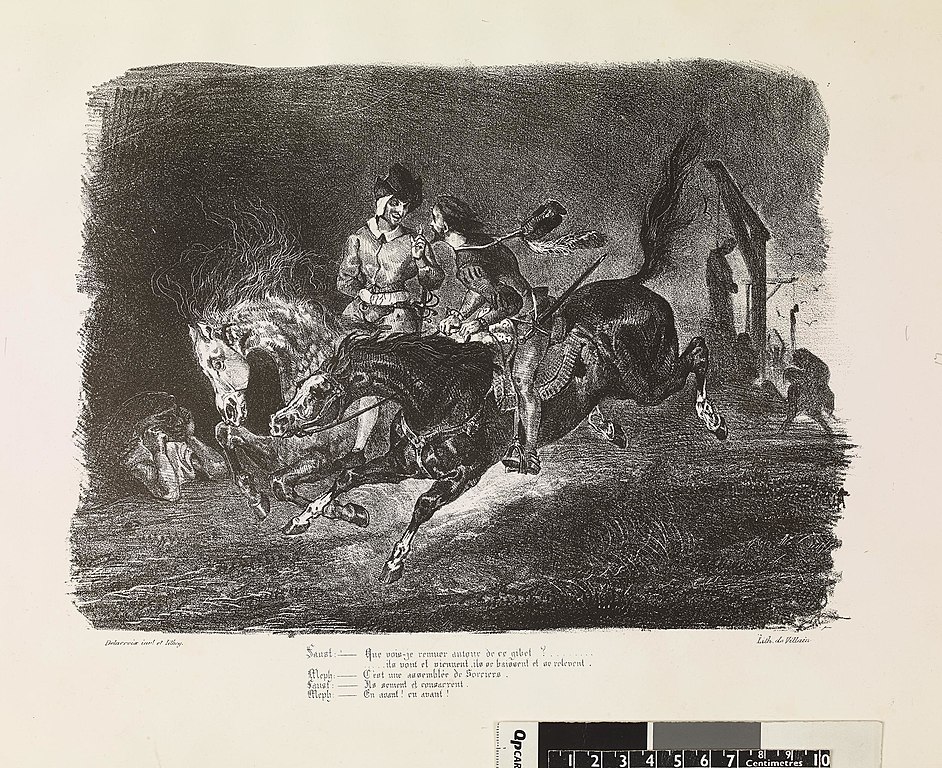

The Tragedy of Faust – Mephistopheles

Separated from Milton by more than a century, the live-affirming poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe took the archetype of Satan in a radically different direction. His poem, The Tragedy of Faust, tells the story of a world-weary professor who — in one last effort to experience true happiness in life — sells his soul to a demon named Mephistopheles.

Although, technically speaking, Mephistopheles is an agent of the Devil rather than the Devil himself, the two are compared so often they may as well be treated as interchangeable. Actually, readers can infer as much simply by taking a closer look at the demon’s name, which consists of the Greek particle for negation (“me”) and the Greek word for love (“philos”).

For the first time since the Book of Job, Satan is not depicted as being the center of the author’s universe. Instead of rebelling against and being expelled from the bureaucracy of heaven, Goethe’s Mephistopheles diligently plays his part and even seems to actively doing so. Rather than being enslaved to his own desires and vendettas, this iteration once again becomes larger-than-life.

His cynicism and quick-wittedness distinguish Mephistopheles from the other characters in the play and make him an incredibly likeable character. Though he continuously intents to collect Faust’s soul and lead him into temptation, the demon actually ends up changing him for the better. Thanks to the journey that Mephistopheles put him on, Faust gains access to heaven in spite of his heresy.

Master and Margarita – Woland

Only an author like Mikhail Bulgakov would be both bold and brave enough to use Satan as the antagonist for his latest novel and also manage to depict him in a way that is as effective as it is believable. In Master and Margarita, the Devil inexplicably manifests in the 1930s Soviet Union to wreak saturnalian havoc on its supposedly atheistic inhabitants.

Fittingly, he appears in a form that would have struck Soviet citizens of the time as noticeably unpleasant: a German exchange professor. His cultural identity can be explained by the lasting influence of Goethe’s Faust, as well as the xenophobic attitude that the Soviets have held towards their romanticist, increasingly fascistic neighbors.

Like Mephistopheles, Woland is part of the religious status quo, though his official job as the tempter and tormenter of man allows him plenty of freedom to air his corrupting yet ultimately benevolent aura. Unlike Mephistopheles, however, Bulgakov’s Devil does not work alone. Throughout Master and Margarita, he is accompanied by an entourage of gambling vampires and cigar-chomping cats.

Asked to explain the differences between this and other versions of the same character, Edward Ericson stated that Woland was heavily shaped by ideas unique to the Russian Orthodox Church. Acting on God’s side of the equation, he is depicted as wise rather than foolish. Instead of being misguided, he is enlightened and not at all trapped in a trap of his own making.