The power of regret fuels our love of the Multiverse

- Wondering “what could have been” is quintessentially human. It is common to ponder how your life might be different had you chosen a different path.

- This is perhaps part of the appeal of the Multiverse; it allows us to explore alternate realities. Hollywood certainly has embraced the concept.

- Whether or not other possible worlds exist in reality, they certainly exist in our imaginations.

We all have regrets. Whether they take the form of marriage proposals, job offers, moving across the country, or having children, there are any number of crucial points in our lives where things could have gone differently. It is in the nature of the human condition to look back and wonder what life would be like if an alternate path had been taken.

Now, we are told, science seems to suggest that perhaps things did go other ways — every possible way, in fact. Not in our own reality, but in other parallel universes, which together comprise a Multiverse. This simple narrative device opens new ways of thinking about the single world we actually do experience.

The Multiverse comes to Hollywood

Hollywood has taken notice. The Marvel Cinematic Universe is expanding fearlessly into a Multiverse, with current box office hit Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness following last year’s Spider-Man: No Way Home, the earlier Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, and TV’s Loki. The Multiverse device allows storytellers to bring heroes into contact with alternate versions of themselves, or with characters that are dead in the original copy of reality. So we see Doctor Strange confronting an evil version of himself, Loki trading barbs with a female Loki, and a bevy of Spider-beings of various races, genders, and species. (Evil doppelgängers are traditionally marked by goatees, but Stephen Strange already has one, so his alternate wears a ponytail.)

It’s not just Marvel. This year’s breakout film is Everything Everywhere All at Once, from directing team Daniels (Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert). It stars Michelle Yeoh as Evelyn Wang, a bedraggled laundromat owner who learns to channel abilities from other versions of herself. Natasha Lyonne’s Netflix series Russian Doll uses time loops and parallel universes to explore the protagonist’s self-undermining impulses. And the animated series Rick and Morty has taken the Multiverse to unprecedented comic extremes, while not shying away from Rick’s struggles with depression.

Possible worlds

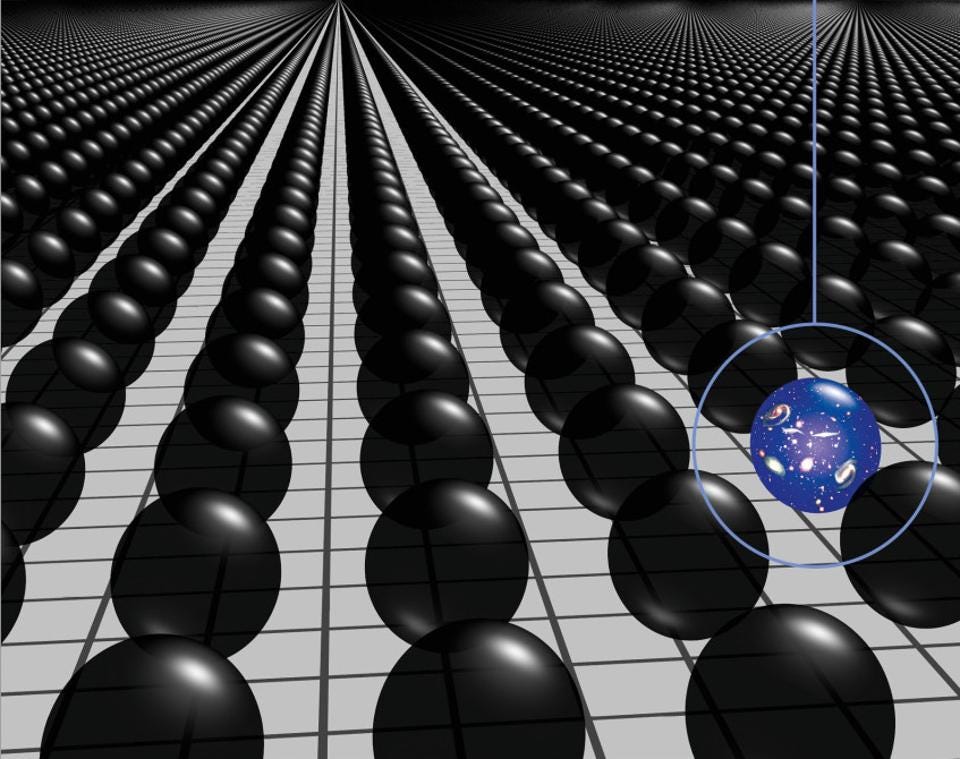

These stories may be inspired in part by speculative ideas from modern physics, but the cinematic Multiverses are closer in spirit to a philosophical idea, that of “possible worlds.” As championed by David Lewis and others, the space of possible worlds is simply the collection of every way the universe could potentially have gone and could go in the future. We don’t envision any mechanism that creates these universes, we just note that we can think about them. Some, like Lewis, take the bold step of claiming that every possible world is equally real, and we just happen to find ourselves in this one.

Whether or not other possible worlds exist in reality, they certainly exist in our imaginations. Every time we wistfully contemplate the past, or dream of the future to come, we cannot help but compare actuality to alternative possibilities. Each of us carries our own version of the Multiverse in our heads. Hollywood has latched onto a way to make this space of possibilities tangible and employ fantasy as a way of making us think about the reality of our lives in a new way.

This idea is less grandiose than it sounds. We all invoke possible worlds in everyday speech, even if we don’t always realize it. Any statement about cause-and-effect relations implicitly refers to what could have happened in other worlds. When you explain, “I was late because of traffic,” you really mean, “In possible worlds that are similar to ours except for the traffic being bad, I would have been on time.”

The ability to reason counterfactually — to ask not just what has happened, what will happen, and what should happen, but also to contemplate all the things that might have happened — is quintessentially human. It lies at the heart of our capacity to imagine possible futures and work to bring them about, as well as our propensity for bargaining: If you do this, I promise to do that. And it opens up the possibility of regret and dwelling on what might have been.

It is therefore natural to ponder alternative histories of the world, and literature has a long tradition of doing just that. The Roman historian Livy conjured a world in which Alexander the Great lived long enough to turn his attention West and ended up in a conflict with Rome. (Spoiler alert: Livy thought the Romans would have defeated him.)

Your personal Multiverse

The modern narrative Multiverse introduces a crucial twist, by allowing characters in alternate realities to cross over and interact with each other. This isn’t an idea that came from science. When physicists think about the Multiverse, they imagine realities that are parallel but strictly separate, with no messages or tourist trips connecting them. I may have any number of goatee-wearing evil twins in alternate realities, but I’m never going to confront any of them. But the ability to imagine hopping from one universe to another is just too tempting. Most importantly, it makes the stories more personal.

It’s when one version of our protagonist gets to meet — and probably fight with — a parallel-universe version that the sparks really fly. Even if the meeting is entirely amicable, each individual cannot help but reflect on their lives when confronted with a concrete manifestation of how things could have gone differently. How would your life have turned out if you had dabbled in dark magic, or mastered kung fu, or flipped genders? These might not be pressing questions for most people, but it’s not hard to see them as metaphors for more common conundrums.

In Everything Everywhere All at Once, Evelyn is informed that she is literally the worst version of herself in all the universes. Many of us have occasionally worried that something along those lines might be the case. Connecting directly with other versions helps Evelyn both recognize the strength within herself, and regain control over a life that had been sliding downhill.

And it’s not just our own decisions. We can’t help but wonder about how the state of the world as a whole might have been different. This is especially vivid in the current moment, where technology has given us a faster and more intimate-seeming connection to events around the globe, without necessarily increasing our ability to affect what happens. It can lead to an impression of powerlessness, where we feel as if our lives are governed by forces and institutions well beyond our control. In such circumstances, alternate-universe scenarios offer a way to think about possibilities that we aren’t able to literally bring about.

Dark side of the Multiverse

There is a darker aspect of Multiverse storytelling. Almost inevitably, a story will begin in a single well-established world, and branch out from there. And with almost equal inevitability, what happens in those other universes will matter less to us than what happens in the first one. Superhero movies will kill off alternate versions of our favorite heroes with an almost gleeful abandon, or even watch whole universes go extinct. The emotional impact of these tragedies is lessened by the feeling that they are somehow less real, and therefore don’t matter in the same way.

There is a lesson there, too, although perhaps an unintentional one. It is natural for us to extend empathy to people we know, those nearby, and those like us. It’s harder to do the same for people and events far away, geographically or culturally. So perhaps it’s no surprise that we care less about deaths in parallel realities. But if the stories we are watching are to be believed, all the universes are equally real. Perhaps that should inspire us to work on extending our empathy more widely.