Nathan Thrall on how to immerse readers in nonfiction writing

- Nathan Thrall’s A Day in the Life of Abed Salama, which won a Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction in 2023, recounts a 2012 car accident in Jerusalem that took the lives of several Palestinian children.

- Thrall uses literary techniques, such as shifting timelines and perspectives, to convey the chaotic and emotional realities of the event.

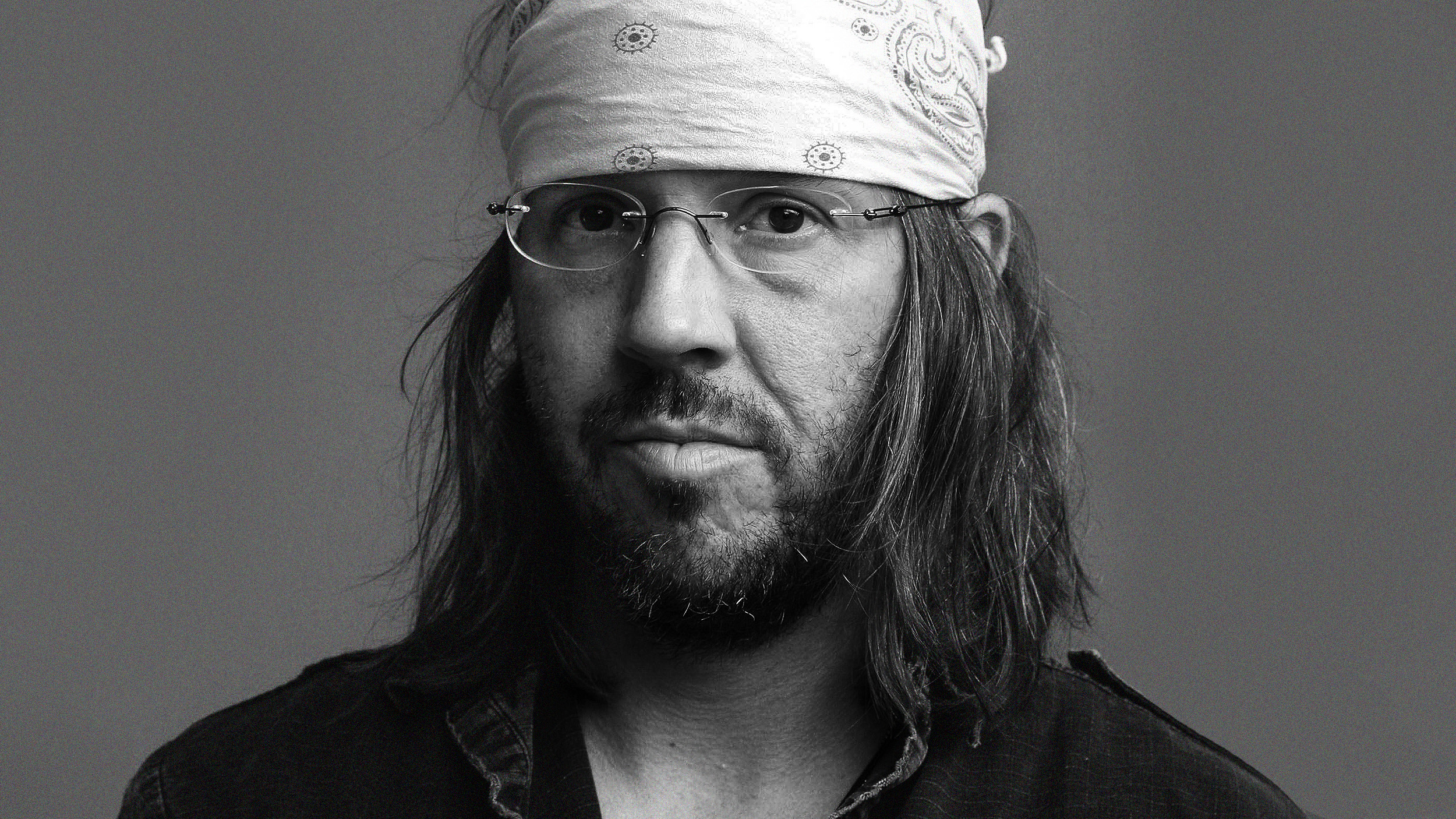

- Big Think spoke to Thrall about the tricky art of writing literary nonfiction, and the differing philosophies about the degree of separation a writer should maintain from their subject.

“During Q&A sessions, readers sometimes refer to it as a novel,” journalist and author Nathan Thrall tells Big Think, “and I have to clarify it’s entirely nonfictional.” Thrall is referring to his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: Anatomy of a Jerusalem Tragedy (2023), which tells the story of a horrific car accident in Jerusalem that claimed the lives of six Palestinian children, including Abed’s five-year-old son, Milad.

That so many readers mistake A Day in the Life for fiction is a testament to Thrall’s skills as a writer, to his ability to describe complicated events and identify with his subjects. However, these kinds of mix-ups also raise important questions about the craft and ethics of nonfiction writing. What distinguishes fiction from nonfiction, and literary nonfiction from ordinary journalism? How do you produce a page-turner without distorting the facts, which may not always lend themselves to an easily digestible narrative? Is it okay for nonfiction writers to take creative liberties, and — if so — when?

Thrall’s insights are not only relevant for aspiring Pulitzer contestants — knowing how to communicate clearly and honestly is helpful in any profession, not to mention our personal lives. Studying well-researched, rigorously fact-checked nonfiction can help us navigate a (social) media landscape riddled with opinions and political propaganda disguised as actual, unbiased news.

Forming the nonfiction experience

A common piece of advice given to both fiction and nonfiction writers is to not overwhelm the reader with detail — to introduce scenes, characters, and ideas piece by piece in the service of clarity. To an extent, A Day in the Life throws this commandment out of the window when, during the book’s prologue, Thrall disorients the reader with exposition. He does so by not only moving through different locations within Jerusalem and the West Bank in mere paragraphs but also by jumping back and forth in time, transitioning between Abed making his way toward the site of the accident and flashbacks that establish his relationship with his son.

While a news reporter might choose to tell the story as it unfolded, Thrall plays with the narrative structure to grip the reader and — more importantly — convey Abed’s confusion and uncertainty. “My goal was to immerse the reader in this world,” Thrall explains, “a chaotic and desperate place: a walled-off ghetto within the Israeli capital surrounded by towering buildings. I wanted to convey the environment’s stark juxtapositions and constant bustle.”

The inventive structure sharply contrasts with Thrall’s plain and simplistic style, inspired by writers like John Hersey and George Orwell, the latter of whom famously argued that flowery, convoluted language obscures and distracts from the objective reality that nonfiction is supposed to represent.

“Writing about Israel and Palestine is particularly challenging because it’s so complex,” Thrall says. “Even experts struggle to fully grasp what’s going on there, and knowledge of the topic varies from reader to reader. Some may not be able to locate these countries on a map, while others are deeply familiar with their history and politics. I wanted to make the subject accessible without oversimplifying it.”

Taking Orwell to heart, Thrall’s creative liberties do not concern substance — that is, the information offered — so much as form, or the way information is presented to the reader. “One example involves a video recording of the immediate aftermath of the accident,” he explains. “The book is written primarily in the past tense. This video, though, I described in present tense because that’s how I experienced it myself, and I think it makes the scene more vivid while at the same time staying true to the facts.”

“Then there’s the structure of the book,” he continues. “The narrative spine is the tragic bus accident. Characters dart in and out of the chronology, which would overwhelm readers if I told everything in a linear fashion. To address this, I chose to focus on the most intense and significant moments for each character and stay with them for a sustained period before moving on. A big challenge here was balancing the chronology of the crash with the characters’ backstories. If one character’s backstory is tied to the Second Intifada and another’s to the First Intifada [two Palestinian uprisings against the Occupation separated by more than a decade], I needed to organize their flashbacks so they flowed logically. These decisions shaped not only the narrative but also which characters were included.”

However, the creative liberties Thrall took were preceded by extensive research, which saw him contacting as many people connected to the accident as he could, from the bus driver to bystanders, neighbors, paramedics, and doctors. He also examined court and police records, including video and audio recordings he acquired either from law enforcement or, if law enforcement refused to cooperate, lawyers.

The only requisite for nonfiction

Asked what distinguishes fiction from nonfiction, Thrall points to a quote from author Richard Flanagan: “He said, ‘Labels are for jam jars,’ and I agree. Good writing is good writing, whether it’s fiction or nonfiction.” The distinction, Thrall insists, has nothing to do with form or style. Any literary device available to fiction writers — be it simile, metaphor, foreshadowing, or internal monologue — should be available to nonfiction writers, provided they put them to good use. “The only requisite for nonfiction is that it’s true. Beyond that, the order of storytelling, perspective, focus, and lens are all open to experimentation. Nothing can be invented unless you explicitly tell the reader you’re inventing.”

Some argue nonfiction writers, like journalists, should maintain a degree of separation between themselves and their subject. This, the argument goes, ensures the writer remains uninvolved and, by extension, unbiased. While such an approach is not without its merits, Thrall, who has been living and working in Jerusalem for several years, dissents — noting that, just as separation does not guarantee objectivity, personal involvement does not inherently result in bias.

“Personally, I’m fully on the side of personal involvement,” he says. “From the start of this project, my goal was to write something that could make people cry, which — for me — meant I had to cry while writing it. Empathy is essential for absorbing and conveying a story. All my writing is emotional in some way. Even my more analytical work, op-eds, and historical essays are driven by emotion, often anger. A Day in the Life covers a broader range of emotions. Not only anger but also sadness, grief, and jealousy.”

Unlike traditional journalism, which (in theory) exclusively concerns itself with reported facts, nonfiction also strives to capture something that can be loosely described as emotional truth: the way facts or external realities impact people mentally and emotionally.

“They’re very different,” Thrall says of the two. “You can gather information, verify it, and still not understand what happened or why someone did something. I don’t feel ready to write until I have that understanding, and I tend to meet with interviewees repeatedly until I can fully identify with their perspective. If writing is, ultimately, about putting yourself and the reader in someone else’s shoes, you need to understand what that person is thinking and feeling.”