French writer Annie Ernaux wins the 2022 Nobel Prize in Literature

- Annie Ernaux's books blur the lines between fact and fiction.

- Her autobiographical novel Cleaning Out, about a college student getting an illegal abortion, is extremely relevant now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned.

- To Ernaux, memory is a boon rather than a burden.

This year’s competition for the Nobel Prize in Literature was especially strong. Contenders included Milan Kundera and Haruki Murakami, who have received just about every writing-related award under the sun, except this one. Many placed their bets on Salman Rushdie. Targeted by Iran’s ayatollahs, Rushdie narrowly survived an attack on his life while lecturing in upstate New York. “His literary accomplishments,” said The New Yorker, “merit recognition from the Swedish Academy.”

That recognition, however, will have to wait. On October 6, the Academy announced that this year’s winner is French writer Annie Ernaux. The driving motivation for this surprising yet by no means unwarranted decision was the Academy’s appreciation of the “clinical acuity with which [Ernaux] uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory.”

Ernaux has been a household name in France for decades. But due to late or under-the-radar translations, the English-speaking world is still discovering her. She was born Annie Duchesne in 1940 in Lillebonne, a town in Normandy, and attended a private Catholic school in Yvetot, where her parents ran a café and grocery store. After Catholic school, Ernaux enrolled at the University of Rouen Normandy, where she started writing her first novel. After university, she found work as a teacher, married, and gave birth to two children.

Her writing is often described as “blurring the line between fact and fiction” — a vague, overused platitude that, in Ernaux’s case, points to her tendency to approach personal, real-life experiences with the same kind of intellectual rigor and emotional intensity commonly found in literature.

Such was the case of her critically acclaimed but controversial 1974 literary debut Cleaned Out, an “autobiographical novel” about a college student suffering from the mental and physical aftereffects of getting an abortion, back when the procedure was still illegal in France. The character, named Denise Lesur, is a foil for her own creator; Ernaux would revisit the desperate search for a backdoor abortion clinic in her 2001 book Happening, adapted into a 2021 film by Audrey Diwan.

The fear and stigmatization explored in Cleaned Out are as recognizable today as they were in the 1970s now that the U.S. Supreme Court has overturned Roe v. Wade, a landmark case that, for a retrospectively brief period of time, compelled lawmakers to recognize abortion as a constitutional right. Ernaux’s newfound relevance was not wasted on reporters; when asked if the Academy’s choice was at all politically motivated, Nobel Prize chair Anders Olsson said, “It’s very important for us also, that the laureate has universal consequence in her work. That it can reach everyone.”

The writing of Nobel Prize-winner Annie Ernaux

For Ernaux, the relationship between her life and her writing was a two-way street. Her husband, Phillipe, had mocked the first draft of Cleaned Out, prompting Ernaux to keep it to herself. When the book was finally published, Phillipe wasn’t happy. If she was capable of writing and publishing an entire book in secret, his reasoning went, then she was surely capable of cheating on him. Ernaux’s entrapped marriage formed the basis for her book A Frozen Woman (1994), while the dreaded affair became the subject for a story titled Simple Passion.

In A Girl’s Story, translated into English as recently as 2020, Ernaux organizes the memories of her earliest sexual experience. Though the event was traumatizing for her, she avoided tackling it in writing for more than six decades because, she felt, it was too complicated. “Had it been a rape,” she told The New York Times, “I might have been able to talk about it earlier, but I never thought about it that way. The man was older – that mattered to me – and I gave in, so to speak, out of ignorance. I don’t even remember saying ‘No.’”

Madeleine Schwartz of The New Yorker further outlines one of the conundrums explored in the book:

“She is pleased to be desired by someone. She does not feel humiliated. But, later, she is mocked, tormented by others who believe that she has debased herself. Those whom she thought of as her friends now treat her like nothing. She feels shame. Is the shame hers? Or is it a reflection of what is expected of her?”

Even though Ernaux deals with very personal experiences, her writing is most certainly of “universal consequence.” Early on in her academic and artistic career she developed an interest in sociology, specifically the work of French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, which taught her how her womanhood and working class background affected the way she was treated as well as perceived by society at large. Both her honesty and her ability to discern subtle, and at times entirely invisible, social forces ensure that her stories are as much a reflection of herself as they are of her readers, female or male. Said sociologist Christine Détrez, to read Ernaux is to experience “the result of a shared condition.”

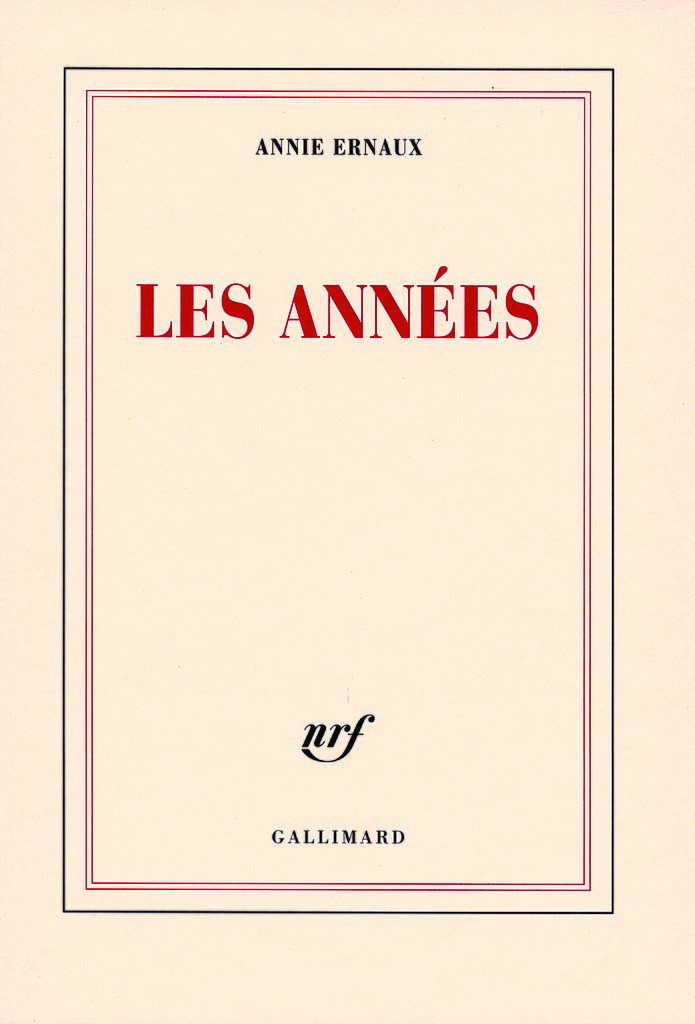

If Cleaned Out marks the start of Ernaux’s oeuvre, The Years (2008) is – at least at present – her magnum opus. The book, a loosely connected collage of memories spanning from 1941 to 2006, blurs the line not between fact and fiction, but between biography and history. An unlikely but helpful comparison, both in format and in depth, is fellow Nobel Prize-winner Svetlana Alexievich’s book Secondhand Time, which narrates the collapse of the USSR through tightly edited conversations with ordinary Soviet citizens.

But where Secondhand Time is about reconstructing past events through a communal effort, The Years is interested primarily in investigating the nature of memory itself, which is as misleading as it is incomplete. Azarin Sadegh, in the Los Angeles Review of Books, puts it this way: “For the reader, the images of the past reveal themselves in broken shapes and forms with holes all over. You leaf through this pile of images and texts and feel immersed in the past. The years have come and gone, and most of the moments lived — captured only in photos and partially in memory— have vanished.”

Fading memories

Ernaux, a quiet person who has spent much of her time at her home in the Parisian suburbs since the start of the pandemic, could not be contacted by the Swedish Academy prior to their public announcement. How she feels about winning the Nobel Prize in Literature is, as of writing this article, unknown.

Fortunately, there are plenty of inspiring quotations that could be used in lieu of closing remarks. Sticking with the overarching theme of memory, one might turn to a short book called I Remain in Darkness, or Je ne suis pas sortie de ma nuit in French. It’s about Ernaux trying to help her mother fight against Alzheimer’s disease, then standing by more or less helplessly as the memory-eating disease robs her of her defining features one by one.

In an aforementioned interview with The New York Times, Ernaux confessed that falling victim to dementia was one of her biggest fears. “Frankly,” she said, “I’d rather die now than lose everything I’ve seen and heard. Memory, to me, is inexhaustible.”