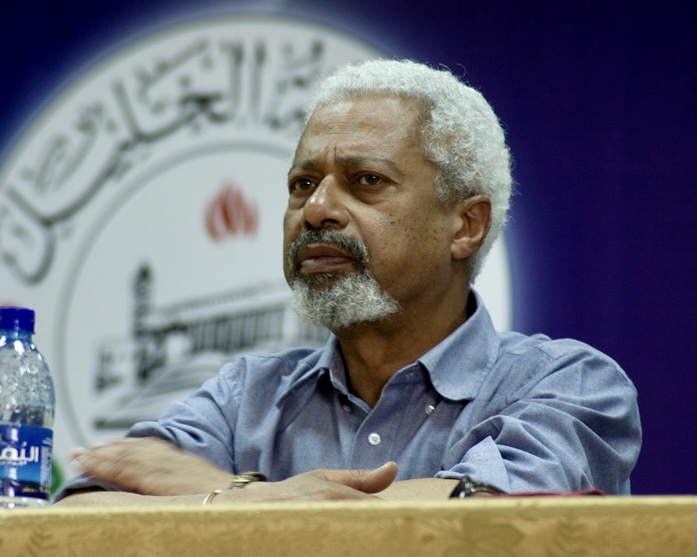

2021 Nobel Prize for literature goes to Zanzibar-born author Abdulrazak Gurnah

- The Swedish Academy has awarded author Abdulrazak Gurnah with the Nobel Prize in literature.

- Gurnah, who was born in Zanzibar, is the first black author to receive the award since Toni Morrison.

- The Academy honored Gurnah for his contributions to the postcolonial canon, including the earnestness with which he described the immigrant experience.

The Swedish Academy on Thursday morning awarded the Nobel Prize for literature to Abdulrazak Gurnah for his “uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents.”

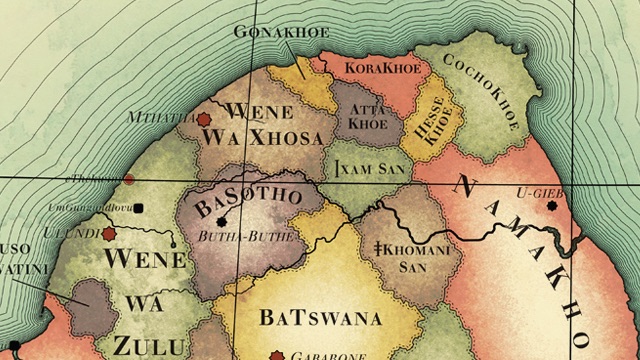

A former professor of English and postcolonial literature at the University of Kent in Canterbury, the 73-year-old author has written ten novels, one of which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and the Whitbread Prize of Fiction. The story of that particular book, titled Paradise, begins in Kawa, a fictional town in Tanzania. Its protagonist is Yusuf, a boy whose father sells him to a merchant to settle a debt. Along with the merchant, an Arab named Aziz, Yusuf travels across the entire African content before getting entangled in the chaos of World War I.

Rumor has it that Paradise was the novel that solidified Gurnah as the committee’s pick for the Nobel Prize. It’s easy to see why. Paradise was, in many ways, the novel that put him on the map. Although structured in the timeless form of a perilous journey, the story somehow manages to avoid the literary clichés and prejudices established by British writers who had previously used Africa as their setting. “No Heart of Darkness in these pages,” NPR critic Alan Cheuse wrote in his original review. “Gurnah gives us a more realistic mix of light and dark.”

According to the British Council, a cultural exchange organization based in London, “…the writings of Abdulrazak Gurnah are dominated by the issues of identity and displacement and how these are shaped by the legacies of colonialism and slavery.” These themes played a key role in Gurnah’s upbringing. The writer came to England at age 18 as a refugee after the sultanate where he had been born and raised was overthrown by local African revolutionaries.

Reflecting on the many differences between life in Canterbury and Zanzibar, Gurnah constructed characters whose own identities were constantly changing based on geographic location and social context. His protagonists often serve as catalysts that force the people they interact with to question their own existence. Time and again, what at first seems set in stone by nature or nurture turns out to be moldable and highly dependent on context — a realization that should cause people to come together, but more often ends up causing unnecessary conflict. The critic Paul Gilroy wrote in his book Between Camps: “When national and ethnic identities are represented and projected as pure, exposure to difference threatens them with dilution and compromises their purities with the ever-present possibility of contamination.”

Abdulrazak Gurnah and the immigrant hybrid

True to the immigrant experience, Abdulrazak Gurnah’s protagonists often exist in a kind of limbo. In his novel Memory of Departure, published in 1987, deprived of his scholarship and robbed of a rightful share to his family’s inheritance, a student struggles to decides to leave his coastal village behind and travel to Nairobi. In Pilgrim’s Way, which came out in 1988, another student – a Muslim – tries to survive the bigoted British community to which he was forced to migrate. In each case, the personal journey the main character undertakes cannot be completed simply by leaving one place or arriving at another. To actually arrive at their destinations and achieve their goals, they must grow as people.

As times change, so does the particular kind of hostility the immigrants in Gurnah’s fiction must face. Where their ancestors were constantly confronted with the conception of the Orient or Other, as described in Edward Said’s Orientalism, their children – who live in a digitized, interconnected, and global economy where movement between different countries and continents is more common than ever – have become what Gilroy refers to as “hybrids.” Standing between different worlds, the younger characters’ “otherness” fuses something that strikes their oppressors as suspiciously familiar.

The immigrant becomes surrounded. While their new culture does not accept them because of their otherness, they also become alienated from their home country, whose people cannot relate to their new, mixed identity. “To have mixed,” wrote Gilroy, “is to have been party to a great betrayal. Any unsettling traces of hybridity must be excised from the tidy, bleached-out zones of pure culture.”

Gurnah, for his part, always felt that in order to fully appreciate a culture’s beauty, you must first understand its history. In an interview with the BBC for a documentary about historical artifacts, the author recalled stumbling across ancient Chinese pottery back when he was still living in Zanzibar. “It was only later on,” he stated, “when you begin to go into museums, or hear these persistent stories of great Chinese armadas that visited East Africa, that the object then becomes valuable, a signifier of something important – a connection.”

Not unlike the Academy Awards, the Swedish Academy has been under mounting pressure to make their nominations more diverse. Until recently, recipients for the Nobel Prize for literature have been overwhelmingly white, male, and European: a possible reflection of the Academy’s research interests as a university firmly lodged inside Scandinavia’s extremely well-organized, but admittedly close-minded, academic landscape. Of the 120 people who have received this award in the past, only 16 had been female. Toni Morrison was the last black recipient before Abdulrazak Gurnah, who in turn succeeds Nadine Gordimer and J.M Coetzee as the fifth winner to come from Africa.

The Academy’s decision to spotlight a non-European author who authentically captured the African immigrant experience and thoughtfully explored the consequences of the continent’s colonization by European powers provides a strong contrast with previous choices. Only two years ago, the Academy became the subject of media criticism for their decision to honor Peter Handke, an Austrian fiction writer and playwright who in turn came under fire for questioning events during the Balkan Wars — notably the Srebrenica massacre that took the lives of 8,000 Muslim men.