Murderabilia: Our morbid fascination with the garish art of American serial killers

- Thanks to popular “true crime” shows, murderers make a killing selling their art.

- While most of this art lacks artistic merit, it offers a window into the twisted minds of its creators.

- In abnormal psychology, art therapy is used to reveal what words cannot express.

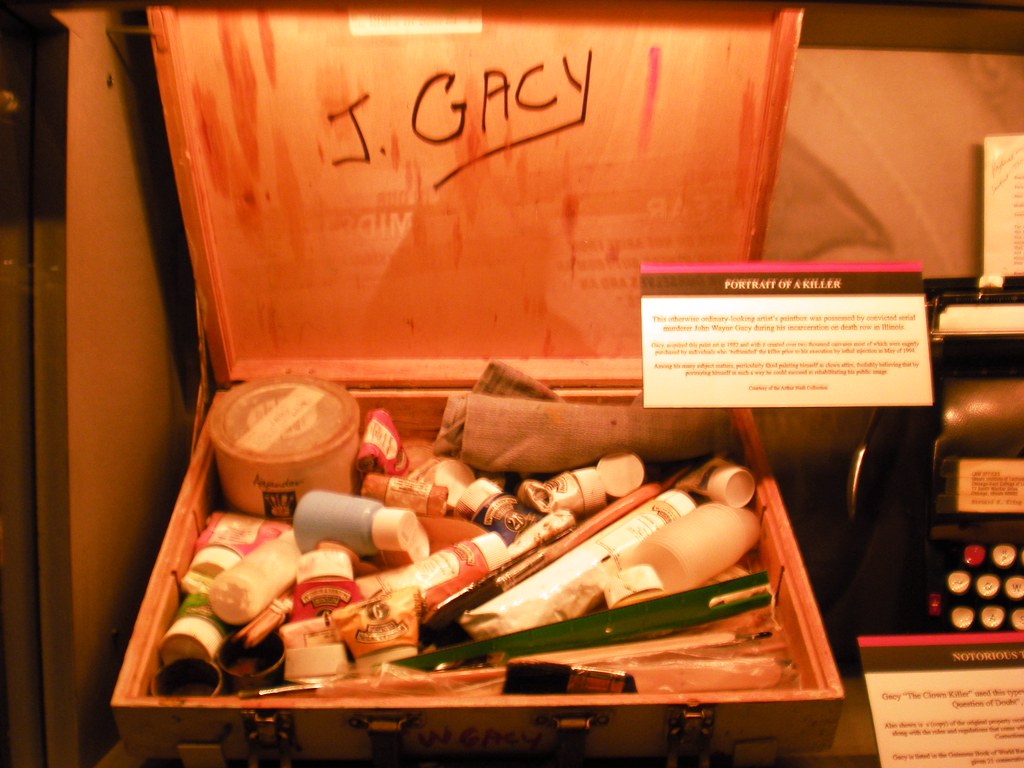

“You never know when your emotions are going to come out again,” Bonnie Schlesinger told the Las Vegas Review-Journal in response to an exhibit of paintings by John Wayne Gacy. “Sometimes they lay dormant for a long time, then they come up.” Schlesinger was not emotional because Gacy’s art touched her, but because Gacy — also known by his alias Pogo the Clown — murdered her brother Michael in 1976.

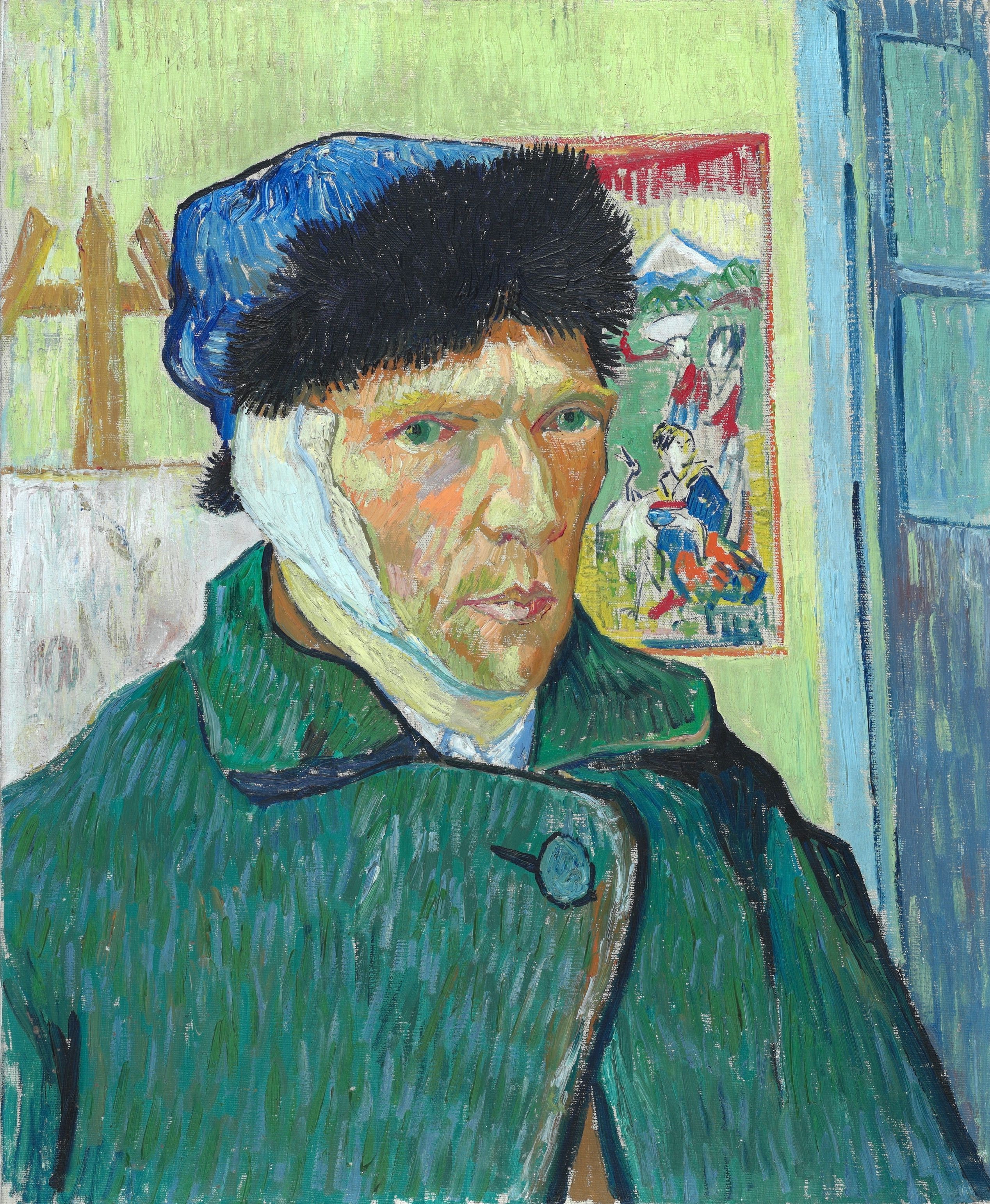

Michael was one of at least 33 young men whom Gacy raped and murdered between 1972 and 1978. In recent years, this number is often listed alongside another, much more insignificant statistic: the 2,000 odd sketches, drawings, and paintings Gacy made before his own death, and which, after he was revealed to be a serial killer, have turned from worthless kitsch into sought-after collector’s items.

Murderabilia

Murder makes money. Lots of money. In 2018, one of Gacy’s clown self-portraits was sold at an auction in Philadelphia for $7,500, way above the $2,000 estimate. At venues specializing in the sale of criminal art or “murderabilia,” like Murder Auction and Supernaught True Crime Gallery, some of his works have gone for as much as $6,000. One in particular — an oil painting of his Chicago home that featured the crawl space where he hid his victims’ remains — was bought for a whopping $175,000.

Gacy wasn’t the only killer moonlighting as an artist. Auctions also have been held for illustrations and paintings from the likes of Richard Ramirez and Charles Manson. Even lesser known killers — that is, those who have yet to receive their own Netflix documentary — are currently selling their scribbles from death row.

Needless to say, these images are as controversial as the people that produced them, and it’s impossible to talk about the subject without confronting a variety of ethical conundrums. Can you appreciate art from serial killers without disrespecting their victims? What does its increasing popularity — and monetary value — say about our culture? Can the work of Gacy and others even be considered art?

The ethics of serial killer art

John Wayne Gacy paintings weren’t always this expensive. Up until the 1990s — the decade of his execution, and years after his arrest — they seldom generated more than $250 per piece. Traders and collectors say that My Favorite Murder, Conversations with a Killer, Mindhunter, or any other show, podcast, or documentary that fuels society’s ever-growing obsession with true crime is the reason behind this price increase.

Of course, the genre is successful in part because it scratches an itch that few other forms of entertainment can. In a 2018 article from the New York Observer, someone who owns a Pogo portrait says people “get ice in their veins” when he shows it to them because “it has been touched and created by pure evil.”

“For many collectors,” the reporter adds, “these paintings feel dangerous and offer the kind of adrenaline rush you can’t achieve just by watching or reading about killers in the abstract.” Buyers come in all shapes and sizes, from teenagers to blue collar workers to celebrities like Johnny Depp and Susan Sarandon. While the latter have been open about their ownership of murderabilia, most buyers keep to themselves because they don’t want to be judged or ridiculed.

Money is a particularly important issue for Andy Kahan, a victims’ rights advocate and outspoken critic of the murderabilia market. “There’s nothing more nauseating and disgusting than to find out the person who murdered your loved ones has items being hawked by third parties for pure profit,” he once said. “I’m a firm believer in free enterprise and capitalism, but I’m also a believer that no one should be able to rob, rape, or murder and turn around and then make a buck off of it.”

Furthermore, according to the New York Observer, it’s not uncommon for murderabilia dealers to write to incarcerated criminals posing as women — young women — stroking their egos and asking for a drawing which, once received, they sell online. When John E. Robinson, a rapist who murdered eight women in Kansas, discovered he had been scammed, he sent a letter to the scammer. “What a loser you are!” It went on: “Preying on those in prison for monetary gain… Talk about a bottom feeder!”

Is murderabilia art — or abnormal psychology?

The aforementioned Las Vegas exhibit — which featured but a small selection of Gacy’s oeuvre — included portraits of Ed Gein, Al Capone, and Adolf Hitler, alongside paintings of Elvis Presley, Jesus Christ, Disney’s seven dwarfs, and Fred Flintstone. Those who visited the exhibit invariably found themselves debating whether Gacy’s work could even be considered art. David Gussak, an art therapist and the chairman of Florida State University’s art education department, believes they cannot. “His art is derivative,” he told the Las Vegas Review-Journal. “It’s flat, it’s boring, in many cases ridiculous and it reveals how much he was trying to mask from the world what he was really about.”

Tasteless in both color and design, these images are valuable and interesting mainly insofar as they reflect the twisted psyche of their creator. The juxtaposition of real-world killers with cartoon characters, for example, mirrors Gacy’s attempt to hide his own murderous self behind his child-friendly clown persona. His inoffensive landscapes, inspired by all-American painters Bob Ross and Thomas Kinkade, similarly helped him blend into his suburban surroundings.

At worst, Gacy’s art provides morbidly fascinating evidence of his criminal insanity. At best, it functions as what Gussak calls a “late-case autopsy into what [he] was about.” Abnormal psychologists have long employed art therapy to unlock what their patients cannot or will not express through words alone. This form of therapy could prove useful for better understanding serial killers as well. In a 2017 study conducted at Loyola Marymount University, therapist Kiran Haynes found that paintings and drawings from Ramirez, Danny Rolling, and Jeremy Bryan Jones contain well-known markers of trauma that inform their diagnoses, including sexual and religious themes that betray how the killers processed guilt.

Rather than sending serial killer art to auctions, Haynes concludes, it should be sent to clinicians for closer examination.