Leonardo da Vinci learned to draw by dissecting dead bodies

- A renowned polymath, da Vinci blurred the distinction between art and science.

- His study of the human body and its biology informed his anatomical drawings and vice versa.

- Separating him from his closest contemporaries was his preference for experimentation over received wisdom.

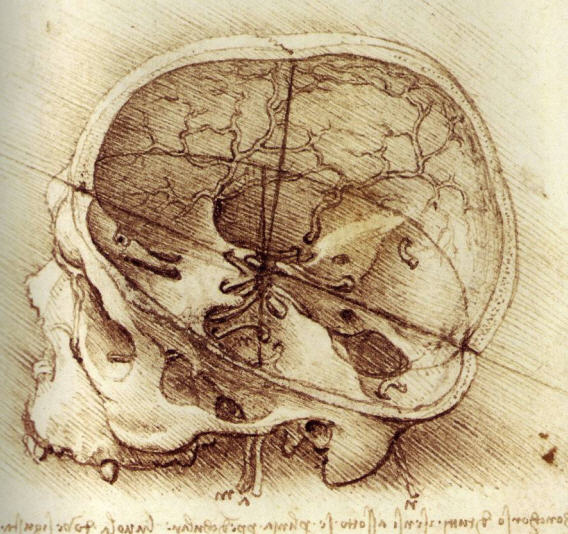

In 1480, Leonardo da Vinci drew two anatomical studies of the human skull: one cut from side to side, the other from top to bottom. In both drawings, a horizontal and vertical axis converge at what he and his contemporaries believed to be the location of the sensus communis or common sense. According to ancient thinkers like Plato and Hippocrates, the sensus communis was the nexus of the soul — the motherboard that animated the body, generated the five senses, and transported the seeds of our species from our lobes to our loins.

These studies, produced when da Vinci was around 37 years old, mark a formative period in the polymath’s career. Born in the early Renaissance, he had grown up around humanism, an intellectual tradition that based its understanding of the world on surviving texts from classical antiquity. It was a tradition he never really embraced. Not because he lacked interest, but because he — a self-described sanza lettere or “illiterate” — did not have a solid grasp of Latin. Unable to dig into the Greek and especially Roman material that so obsessed his peers, da Vinci’s education took a different and ultimately more fruitful approach.

Instead of turning to the past for answers, he turned simply to himself — that is, to his own observations and experiences. This not only allowed him to calculate the gravitational constant and invent the parachute, but also to create paintings as deceptively lifelike as the Last Supper and the Mona Lisa.

Anatomy of a masterpiece

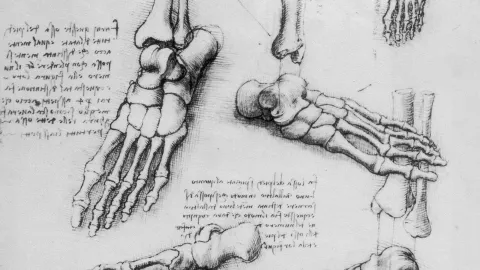

Da Vinci’s art is often described as realistic, a characteristic he achieved in part through his use of sfumato. Italian for “vanished” or “evaporated,” it is a blending technique that creates imperceptible transitions between light and dark colors, resulting in images that appear less like paintings and more like photographs. Equally important was his comprehension of anatomy. To faithfully reproduce the human body, Da Vinci knew he needed to study not only the network of muscles hidden underneath the skin, but the bones and organs, too.

Da Vinci did not become a master painter overnight. As Martin Clayton, the head of Prints and Drawings at Windsor Castle’s Royal Collection Trust (which holds the largest collection of da Vincis on the planet), discusses in his book Leonardo da Vinci: The Mechanics of Man, his “early anatomical studies were rather unfocused.” Acknowledging the body’s “structural, mechanical perfection,” he knew that every part of it was somehow connected to each other. He just didn’t know exactly how.

Unfortunately, says Clayton, “Leonardo was unable to get very far with most of these subjects.” Clayton writes:

“His status was that of a craftsman, and unsurprisingly he found human material for dissection hard to come by… Many of Leonardo’s early anatomical observations were thus based on a blend of received wisdom, animal dissection, and mere speculation.”

All this changed in the winter of 1507-08, when an excited da Vinci received permission to perform his first autopsy. It would not be his last. Only a year later, he claimed to have cut open more than ten people. By the end of his life, that number had risen to more than 30.

The more autopsies da Vinci performed, the more his drawings diverged from their classical predecessors. Where the ancient Greeks and Romans studied human bodies to imagine their ideal form, da Vinci wanted to depict his subjects as they were, as nature had designed them. These conflicting philosophies clashed in what has since become one of da Vinci’s most famous works: Vitruvian Man. A work of science as much as it is a work of art, it was inspired by a remark that the Roman architect Vitruvius made in his text De Architectura:

“Just so the parts of Temples should correspond with each other, and with the whole. The navel is naturally placed in the centre of the human body, and, if in a man lying with his face upward, and his hands and feet extended, from his navel as the centre, a circle be described, it will touch his fingers and toes. It is not alone by a circle, that the human body is thus circumscribed, as may be seen by placing it within a square. For measuring from the feet to the crown of the head, and then across the arms fully extended, we find the latter measure equal to the former; so that lines at right angles to each other, enclosing the figure, will form a square.”

Da Vinci was not the first to draw a Vitruvian Man. Several Renaissance artists tried to illustrate the image that Vitruvius describes. However, each got so caught up in following the architect’s flawed directions that their “men” ended up looking anything but human. Da Vinci’s depiction is special in that he started with drawing an anatomically accurate representation of the body and then fitting the square and circle to that body, rather than the other way around.

Science of art, art of science

On closer inspection, the qualities that made Leonardo da Vinci a groundbreaking scientist seem to be the same qualities that made him a groundbreaking artist. As the historian James Ackerman surmises in an article:

“He was a protoscientist in the modern sense of what constitutes science, bringing to his investigation of the natural world not only an extraordinary artistic imagination, which led him to innumerable original discoveries, but a unique and idiosyncratic intellectual position that helped him to circumvent the mental blocks of his contemporaries.”