Norwegian dramatist Jon Fosse wins the 2023 Nobel Prize in Literature

- Jon Fosse’s magnum opus, the Septology series, is written in a stream-of-consciousness style.

- Half poet and half prose writer, Fosse’s work is to be experienced rather than processed, felt rather than analyzed.

- Contrary to other Norwegian best-sellers, Fosse writes in Nynorsk, a more obscure standard.

On October 5, the Swedish Academy awarded the 2023 Nobel Prize in Literature to Norwegian author and playwright Jon Fosse. The Academy recognized the writer for his “innovative plays and prose, which give voice to the unsayable.” Over the course of his professional career, which began with the publication of his first novel, Red, Black in 1983, the 64-year-old Nobel laureate has written over 40 plays and 30 books, alongside several dozens of essays, short stories, and poetry collections.

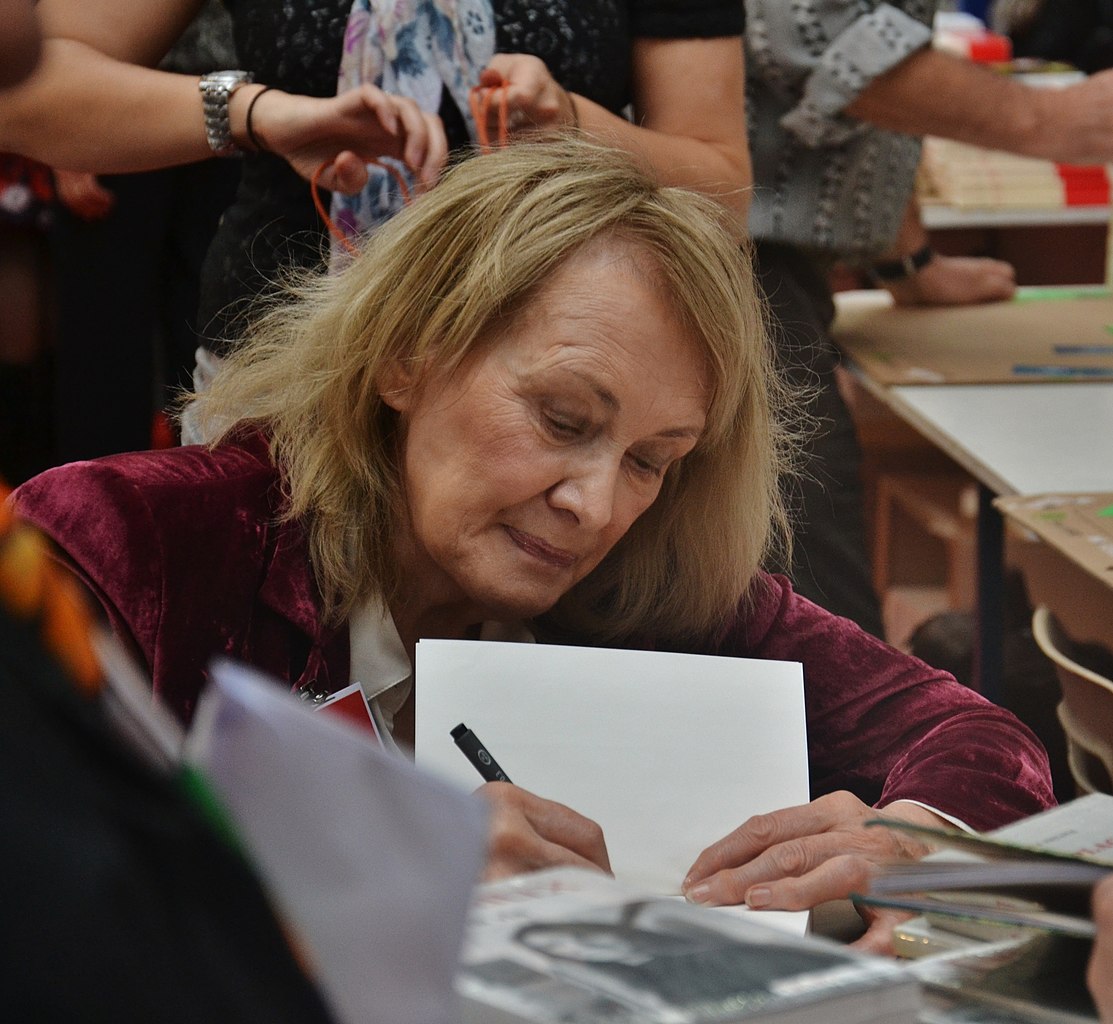

Fosse wasn’t expected to win the prestigious award. Ladbrokes, a sports betting company at the forefront of Nobel predictions, had previously identified Japan’s Haruki Murakami, Canada’s Margaret Atwood, and India’s Salman Rushdie as the most likely candidates. Also in the race were Chinese fiction writer Can Xue and Kremlin critic Lyudmila Ulitskaya. Not even fellow Scandinavians believed that Fosse stood a chance, with many proclaiming that the Swedish Academy electing a Norwegian recipient would be “too obvious.” Elsewhere, critics of the Academy’s admittedly Eurocentric track record — 15 of the past 20 prize winners (including last year’s Annie Ernaux) have been white — expected the institution to pick a person of color.

That’s not to say Jon Fosse isn’t worthy of the Nobel Prize. Far from it. Born in the coastal city of Haugesund, his early sources of inspiration included his guitar and the waves he could see rolling down the fjord from his bedroom window. A sentimental soul, his real name is Jon Olav, with Fosse being Norwegian for “waterfall.” Water is a suitable analogy for Fosse’s writing, which flows from clause to clause with little to no punctuation. Each installment of his Septology series, chronicling the life of a painter and widower, reads like one uninterrupted 700-page sentence.

The following excerpt, from a novel titled Aliss at the Fire, gives an impression of his stream-of-consciousness style:

I see Signe lying there on the bench in the room and she’s looking at all the usual things, the old table, the stove, the woodbox, the old paneling on the walls, the big window facing out onto the fjord, she looks at it all without seeing it and every-thing is as it was before, nothing has changed, but still, everything’s different, she thinks, because since he disappeared and stayed gone nothing is the same any-more, she is just there without being there, the days come, the days go, nights come, nights go, and she goes along with them, moving slowly, without letting any-thing leave much of a trace or make much of a difference, and does she know what day it is today? she thinks, yes well it must be Thursday, and it’s March, and the year is 2002, yes, she knows that much, but what the date is and so on, no, she doesn’t get that far, and anyway why should she bother? what does it matter any-way? she thinks, no matter what she can still be safe and solid in herself, the way she was before he disappeared, but then it comes back to her, how he disappeared, that Tuesday, in late November, in 1979, and all at once she is back in the emptiness…

Jon Fosse: poet or prose writer?

Although not technically a poet, Fosse’s writing and writing process are in many ways more akin to poetry than prose. Valuing rhythm over content, his work has to be experienced rather than processed, felt rather than thought over. Comparing Norway’s most accomplished writers to the Beatles, Damion Searls, a translator who said he was moved to tears while reading Septology, identified Fosse with band member George Harrison: “…the quiet one, mystical, spiritual, probably the best craftsman of them all.” Fosse might agree, stating in a 2018 interview with the Financial Times that “you don’t read my books for the plots.”

Where prose tries to make sense of human existence, poetry has historically embraced its inherent inexplicability. Fosse, too, thinks of his work as transcendent. He told the LA Review of Books:

“When I sit down and start writing, I never intend for anything to happen. I listen to what I’m writing, and what happens happens. Of course, you can interpret it in several ways. It’s not my job to explain it — I’m just a writer. My interpretation would be less valuable than yours. But I feel that if I’m writing well, there’s a lot of what I might call meaning, even a kind of message. But I cannot put it into simple words. I can only guess as much as you can.”

Where prose deals exclusively in language, Fosse attempts to move beyond the written or even spoken word. From the same interview:

“When I manage to write well, there is a second, silent language. This silent language says what it is all about. It’s not the story, but you can hear something behind it — a silent voice speaking. It’s this that makes literature work well for me.“

While beloved by many, Fosse’s work concerns the few. His Septology, alongside his other writing, generally centers around society’s downtrodden: the working poor, alcoholics, social outcasts. For Norwegians, this association holds a double meaning, as Fosse writes not in Bokmål, the written standard used by 85 to 90% of the country, but in Nynorsk, a less popular but more distinct literary form derived from 19th-century country dialects. It’s a form of expression many English-language readers have been interested in picking up, not only to get closer to Fosse’s mind but also because English and Norwegian, belonging to the same linguistic family, are more similar than one might think.

Nobel Prize-winner is hardly the most treasured title under Fosse’s belt. For years, Norwegian readers have referred to him as “the new Ibsen,” the spiritual successor of the famed 19th-century playwright and theater director. In some ways, Fosse has even surpassed Ibsen. With plays translated into more than 50 languages — according to his translator Ann Henning Jocelyn — and performed in over 60 countries across the world, Jon Fosse has, for some years now, been regarded as the “most produced living dramatist” on Earth.