What Greek epics taught me about the special relationship between fathers and sons

Father’s Day inspires mixed emotions for many of us. Looking at advertisements of happy families could recall difficult memories and broken relationships for some. But for others, the day could invite unbidden nostalgic thoughts of parents who have long since died.

As a scholar of ancient Greek poetry, I find myself reflecting on two of the most powerful paternal moments in Greek literature. At the end of Homer’s classic poem, “The Iliad,” Priam, the king of Troy, begs his son’s killer, Achilles, to return the body of Hektor, the city’s greatest warrior, for burial. Once Achilles puts aside his famous rage and agrees, the two weep together before sharing a meal, Priam lamenting the loss of his son while Achilles contemplates that he will never see his own father again.

The final book of another Greek classic, “The Odyssey,” brings together a father and son as well. After 10 years of war and as many traveling at sea, Odysseus returns home and goes through a series of reunions, ending with his father, Laertes. When Odysseus meets his father, however, he doesn’t greet him right away. Instead, he pretends to be someone who met Odysseus and lies about his location.

When Laertes weeps over his son’s continued absence, Odysseus loses control of his emotions too, shouting his name to his father only to be disbelieved. He reveals a scar he received as a child and Laertes still doubts him. But then Odysseus points to the trees in their orchards and begins to recount their numbers and names, the stories Laertes told him when he was young.

Since the time of Aristotle, interpreters have questioned “The Odyssey”’s final book. Some have wondered why Odysseus is cruel to his father, while others have asked why reuniting with him even matters. Why spend precious narrative time talking about trees when the audience is waiting to hear if Odysseus will suffer at the hands of the families whose sons he has killed?

I lingered in such confusion myself until I lost my own father, John, too young at 61. Reading and teaching “The Odyssey” in the same two-year period that I lost him and welcomed two children to the world changed the way I understood the father-son relationship in these poems. I realized then in the final scene, what Odysseus needed from his father was something more important: the comfort of being a son.

Fathers and sons

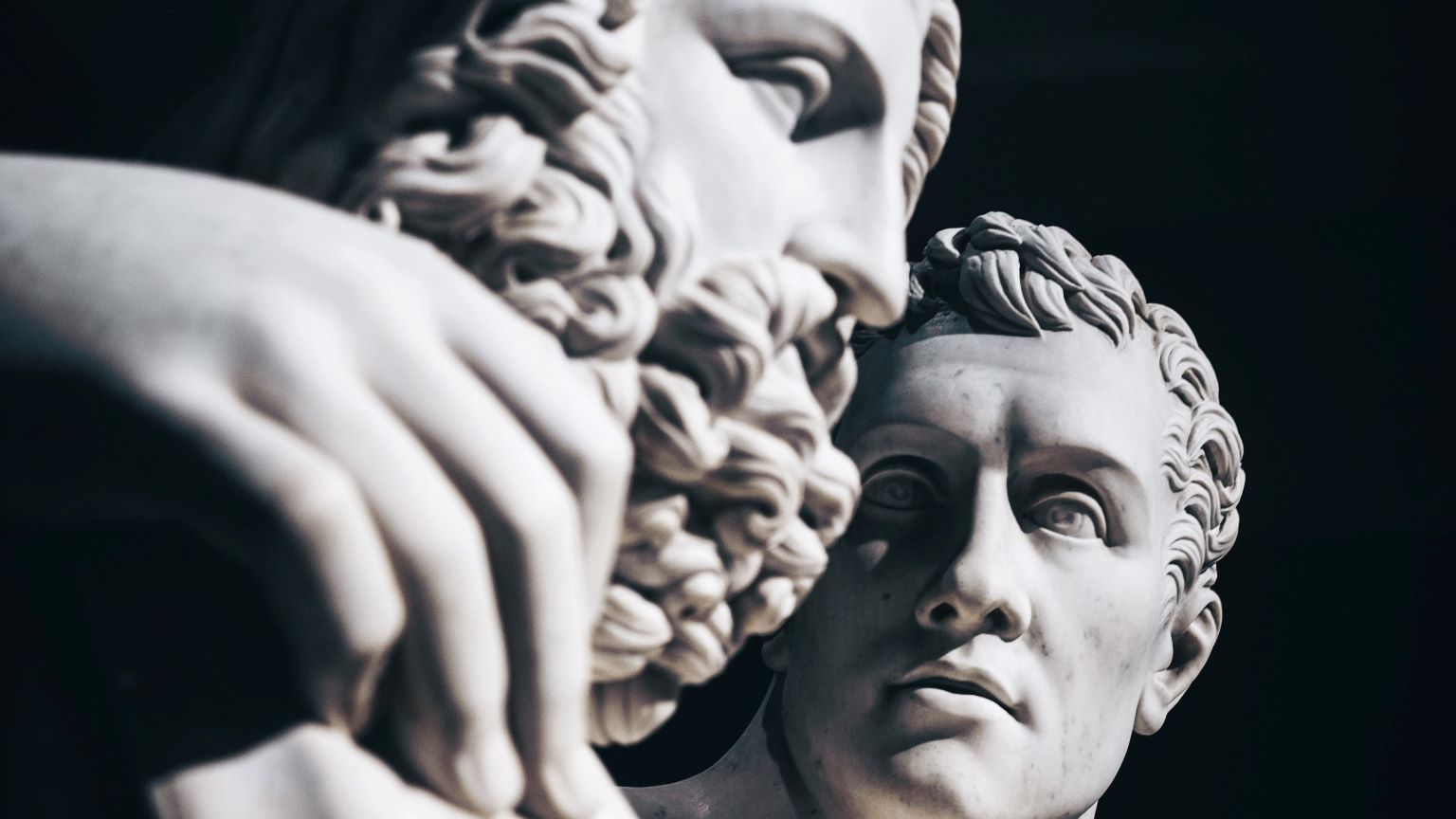

Fathers occupy an outsized place in Greek myth. They are kings and models, and too often challenges to be overcome. In Greek epic, fathers are markers of absence and dislocation. When Achilles learns his lover and friend, Patroklos, has died in “The Iliad,” he weeps and says that he always imagined his best friend returning home and introducing Achilles’ son, Neoptolemus, to Achilles’s father, Peleus.

The Trojan Prince Hektor’s most humanizing moment is when he laughs at his son’s startled cry at seeing his father’s bloodied armor. Priam’s grief for Hektor’s loss stands in for the grief of all parents bereft of children taken too soon. When he hears of the death of his son, he lies prostrate on the earth, covering his head with ash and weeping. The sweetness of Hektor’s laugh foreshadows the bitter agony of his father’s pain.

I don’t think I had a grasp of either before I became a father and lost one.

How stories bring us home

Odysseus’ reunion with his father is crucial to the completion of his story, of his return home. In Greek the word “nostos,” or homecoming, is more than about a mere return to a place: It is a restoration of the self, a kind of reentry to the world of the living. For Odysseus, as I explore in my recent book “The Many-Minded Man: The Odyssey, Modern Psychology, and the Therapy of Epic,” this means returning to who he was before the war, trying to reconcile his identities as a king, a suffering veteran, a man with a wife and a father, as well as a son himself.

Odysseus achieves his “nostos” by telling and listening to stories. As psychologists who specialize in narrative therapy explain, our identity comprises the stories we tell and believe about ourselves.

The stories we tell about ourselves condition how we act in the world. Psychological studies have shown how losing a sense of agency, the belief that we can shape what happens to us, can keep us trapped in cycles of inaction and make us more prone to depression and addiction.

And the pain of losing a loved one can make anyone feel helpless. In recent years, researchers have investigated how unresolved or complicated grief – an ongoing, heightened state of mourning – upends lives and changes the way someone sees oneself in the world. And more pain comes from other people not knowing our stories, from not truly knowing who we are. Psychologists have shown that when people do not acknowledge their mental or emotional states, they experience “emotional invalidation” that can have negative mental and physical consequences from depression to chronic pain.

Odysseus does not recognize the landscape of his home island of Ithaca when he first arrives; he needs to go through a process of reunions and observation first. But when Odysseus tells his father the stories of the trees they tended together, he reminds them both of their shared story, of the relationship and the place that brings them together.

Family trees

“The Odyssey” teaches us that home is not just a physical place, it is where memories live – it is a reminder of the stories that have shaped us.

When I was in third grade, my father bought several acres in the middle of the woods in southern Maine. He spent the rest of his life clearing those acres, shaping gardens, planting trees. By the time I was in high school, it took several hours to mow the lawn. He and I repaired old stone walls, dug beds for phlox, and planted rhododendron bushes and a maple tree.

My father was not an uncomplicated man. I probably remember the work we did on that property so well because our relationship was otherwise distant. He was almost completely deaf from birth, and this shaped the way he engaged with the world and the kinds of experiences he shared with his family. My mother tells me he was worried about having children because he wouldn’t be able to hear them cry.

He died in the winter of 2011, and I returned home in the summer to honor his wishes and spread his ashes on a mountain in central Maine with my brother. I had not lived in Maine for over a decade before his passing. The pine trees I used to climb were unrecognizable; the trees and bushes I had planted with my father were in the same place, but they had changed: they were larger, grown wilder, identifiable only because of where they were planted in relation to one another.

That was when I was no longer confused about the walk Odysseus took through the trees with his father, Laertes. I cannot help but imagine what it would be like to walk that land with my father again, to joke about the absurdity of turning pine forests into lawn.

“The Odyssey” ends with Laertes and Odysseus standing together with the third generation, the young Telemachus. In a way, Odysseus gets the fantasy ending Achilles couldn’t even imagine for himself: He stands together in his home with his father and his son.

In my father’s last year, I introduced him to his first grandchild, my daughter. Ten years later, as I try to ignore another painful reminder of his absence, I can only imagine how the birth of my third, another daughter, would have lit up his face.

“The Odyssey,” I believe, teaches us that we are shaped by the people who recognize us and the stories we share together. When we lose our loved ones, we can fear that there are no new stories to be told. But then we find the stories that we can tell our children.

This year, as I celebrate a 10th Father’s Day as a father and without one, I keep this close to heart: Telling these stories to my children creates a new home and makes that impossible return less painful.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.