5 beloved fantasy novels based on real history

- Many fantasy novels are praised for their world-building and the depth of their lore.

- However, more than a few of these fantasy worlds owe a debt to the real-life history on which they are based.

- From ancient Chinese journeys to 19th-century American politics, we explore the historical influences of five famous fantasy works.

A surprisingly effective way of understanding our world is to look at it through the lens of fiction. Many of the greatest adventures of the page and screen take place in imaginary worlds that bear a striking resemblance to our own. That’s because their authors used actual history to lay the bedrock upon which they built their tales.

We’ll look at five fantasy stories that turned real-world history into fantastic stories. Some spoilers ahead.

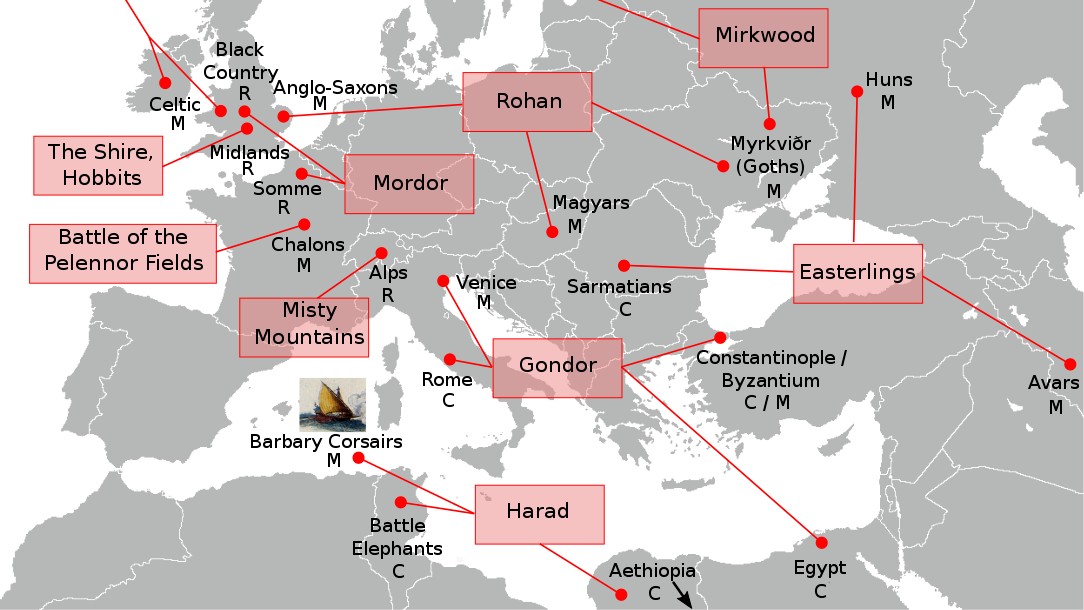

The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

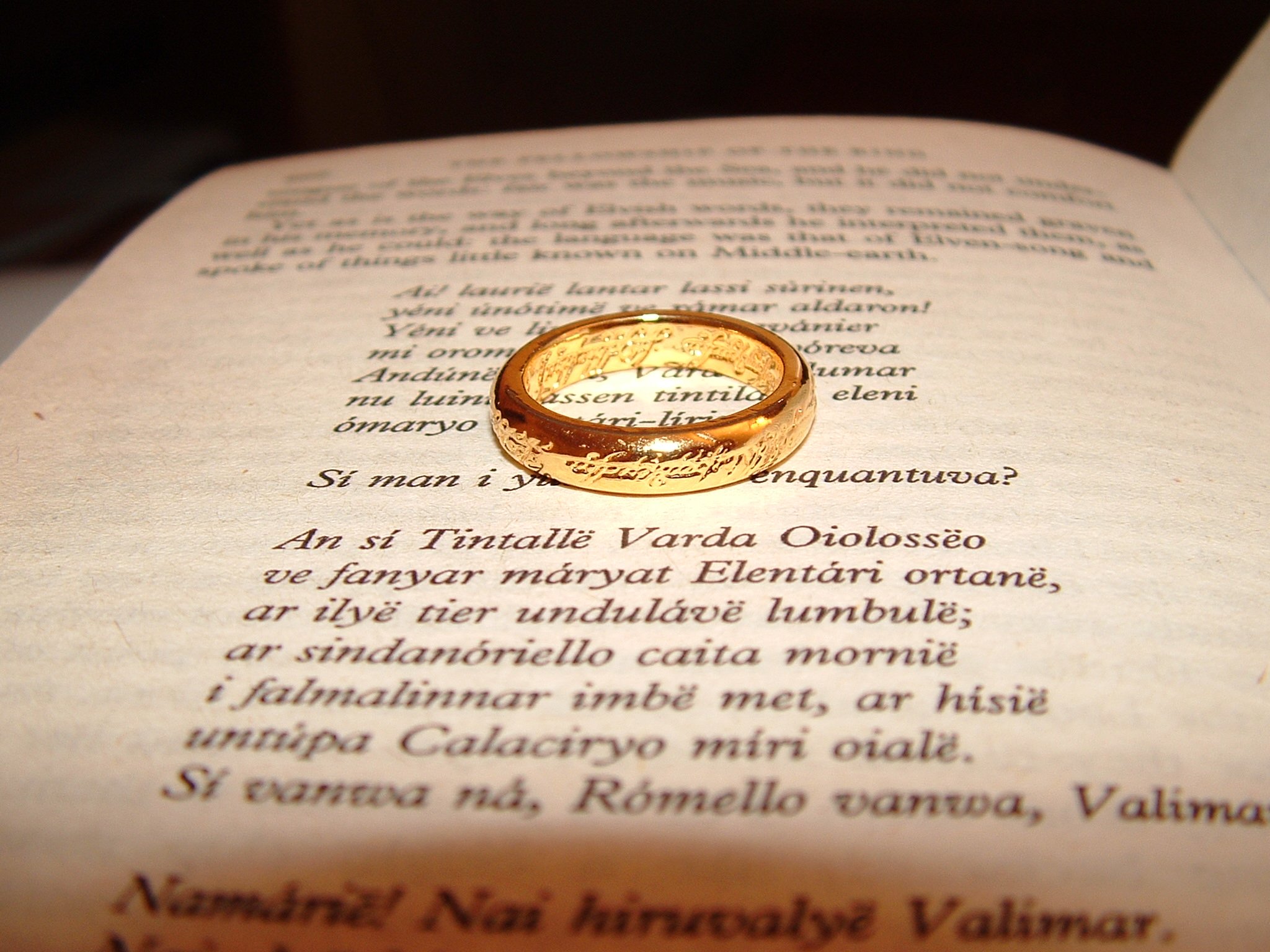

More ink has been split over The Lord of the Rings books and their intricacies than blood at the Siege of Minas Tirith. The brilliance of J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic chronicling how a magic ring was created, lost, found, and destroyed has captivated millions since its initial publication in 1954. Debate rages over the finer details of the historical basis for Middle Earth. Still, it is difficult to ignore the influence of European history and English geography — especially given how deep into the lore Tolkien proved willing to delve.

Here, we will focus on the novel’s penultimate chapter, “The Scouring of the Shire.” The chapter is often overlooked by the casual fan and left out of adaptations. For instance, it is only referenced as a possibility should the heroes fail in Peter Jackson’s award-winning film trilogy. Despite the richness of any possible allegorical interpretations, it is a bit of an anti-climax.

Despite Tolkien’s objections, many critics view the chapter as a take on post-WWII Britain. In particular, it can be viewed as a send-up of the democratic socialist administration of Clement Attlee’s Labour government, a comment on Britain’s industrialization, or even as an allegory for fascism.

Upon their return to the Shire, the hobbits find ugly, polluting buildings replacing many familiar places since their departure. Countless trees have been cut down and new mills are poisoning the rivers. Many inns and joyful pubs have been closed, and the hobbits are forced to sleep in a drab police station for a new security force. A slew of new rules imposed by a new government nearly gets them all jailed. The “Shirriff,” who tries to take them in, remarks, “I am sorry, Mr. Merry, but we have orders”. Gangs called “ruffians” enforce the will of their leader through violence.

Many basic goods, such as the “pipeweed” the characters enjoy smoking, are unavailable and said to have been exported to parts unknown. The hobbits lead a rebellion, ultimately restoring the environment and social order to their the prior, idyllic states.

These references would have been obvious to a contemporary reader of Tolkien’s work but are less clear from a 21st-century perspective.

For instance, the post-war government in Britain would have been many things that Tolkien disliked — socialist, modernizing, industrial, and bureaucratic. One common complaint during the years of Attlee’s Labour government was that rationing continued well after the war ended and some items were always in short supply. A common euphemism for this was that the item was “gone for export.” The polluting buildings that greet the hobbits after their return from battling evil would have seemed rather on the nose for returning soldiers from either world war.

On a darker note, the chapter also makes clear references to the fascist regimes of Europe. The returning hobbits only make it a day before breaking enough rules to be subject to arrest, goons suppress dissent with violence, and many people are content to keep their heads down. Despite few people seeming to like or benefit from the changes, few are willing to resist them. Indeed, one of the few people who seems to have gained anything is the mysterious leader of the ruffians, with his mind of metal and wheels.

Journey to the West by Wu Cheng’en

A bit of a cheat for this list, Journey to the West takes place in a fantastical version of our world rather than a fully invented one, but it cannot be left out of any discussion on this topic. It is perhaps the most famous work of Chinese literature, and its many incarnations and reinterpretations continue to thrill readers long after its publication in the 16th century.

Journey to the West is the story of how a monk, Tang Sanzang, and his entourage head to India to find better records of Buddhist wisdom in hopes of bringing them back to China. His associates include the powerful but hubristic Monkey King, a reformed man-eating beast, and “Pigsy” — a former admiral exiled from heaven and accidentally made into a half-man, half-pig monster by a quirk in celestial bureaucracy. Along the way, they face many monsters, troublesome humans, and supernatural obstacles. After meeting the Buddha himself, they return to China with the improved texts and reach varying levels of spiritual enlightenment.

Despite the fantastical elements and geography, the story is based on real history. A monk did spend seventeen years traveling to India and back to collect better texts for Chinese Buddhists. His name was Xuanzang, and his record of the expedition, Records of the Western Regions, is an invaluable source of information on the cultures and nations he encountered on the long hike from China to South Asia. His writings confirm the dates for several known events, persons, and books — even if some of his accounts are almost as implausible as the exploits of the Monkey King.

Xuanzang returned to China with hundreds of Buddhist texts, which he then worked on translating for many years. His Chinese language versions of some Buddhist sutras, most notably the Heart Sutra, proved the foundation for much later religious commentary in China and other East Asian countries.

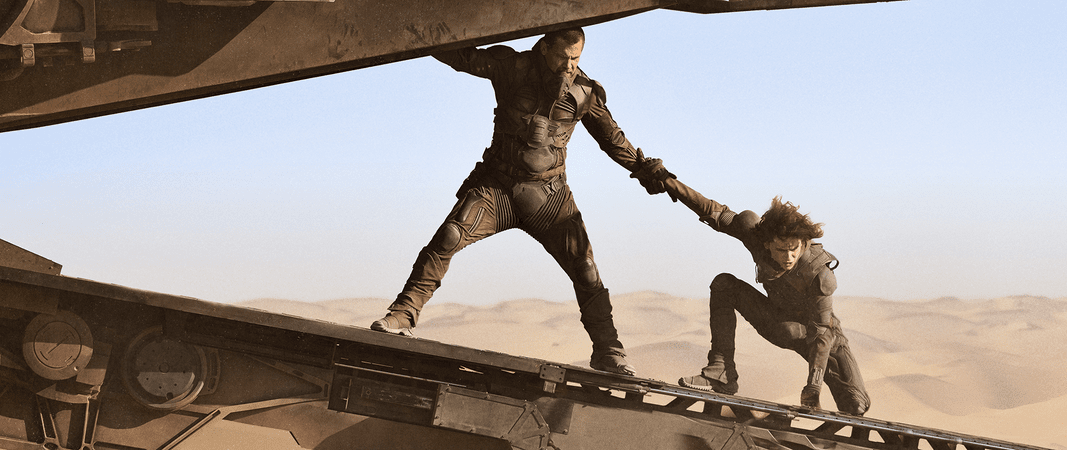

Dune by Frank Herbert

While technically a sci-fi novel, Dune’s exploration of religious themes, the feudal nature of its governmental structure, and the occasionally magical qualities of in-universe items and substance make it perfectly at home on a list like this. Herbert’s novel is a story of humanity’s mental and social evolution into the far future, control of the mystical “melange,” and the people who live on the only planet that produces it.

The Dune universe was fairly complex from the outset, and that complexity grew with each subsequent book, game, and film adaptation. Sticking with what Herbert wrote in the first novel, we can see an all-too-familiar world that revolves around the control of resources.

Melange, also known as “the spice,” is a psychotropic drug that can only be found in the deserts of Arrakis. The drug improves a user’s vitality, awareness, and lifespan. It also makes interstellar space travel possible through its mind-expanding effects. It is extremely addictive, and withdrawal is fatal. Because the Imperium, which controls all known human settlements in the universe, depends entirely on it and its consistent production, melange is the most valuable and sought-after resource in the universe.

Unfortunately, Arrakis is a brutal planet. The process of mining melange tends to attract giant sandworms that will gladly eat mining crews. Attacks by Fremen, the planet’s indigenous people who want an end to imperialism, are also an occupational hazard. The Fremen also practice a faith called “Zensunni” and await the arrival of a messianic leader who will lead them. They find one in the foreigner Paul Atreides.

The setting should be familiar to anybody who has read about the history of the Middle East. Paul’s story has often been compared to that of Lawrence of Arabia. Both figures enter an Islamic desert society dominated by foreign powers, including the ones they represent. They learn how to lead the people militarily. As the wars drag on, both characters question their actions while swept up by forces they cannot control, and how heroic either of them actually ends up being is open for debate.

The only reason anybody who doesn’t live on Arrakis cares about it is the presence of melange (say the planet’s name slowly and then pronounce the first A as an I). The need for a continuous supply of the stuff drives every aspect of the book’s plot. To control the spice is to have unquestioned power and endless wealth. The various representatives of the Imperium endlessly scheme and plot to have it. Later books show that the planet becomes a backwater when an alternative supply is found.

Perhaps uniquely on this list, Herbert’s writings have only become more relevant over time. He once mused that when he wrote the book, there was no real-life version of CHOAM — the in-universe conglomerate run by the nobility with a monopoly on nearly everything worth buying. Then OPEC came into existence to make up for it.

A Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin

A Song of Ice and Fire is George R.R. Martin’s still ongoing series about the noble houses of Westeros and their power struggle to control the Iron Throne. The many plot lines of the novels include the attempts of the daughter of a deposed dynasty to retake the throne, the political jockeying of those currently in power, the impending horror of a winter with an unpredictable duration, and the effects of having been close to power on the children of a king’s advisor.

Spoiler: Many people die. Don’t get attached to anybody. Also, maybe skip season eight if you’re watching the HBO adaptation, Game of Thrones.

Martin has been open about how large parts of the story are loosely based on the Wars of the Roses, a series of 15th-century British civil wars. The map of Westeros bears a passing resemblance to the British Isles, and the main cast bears more than a passing resemblance to the major players of that historical conflict. Unfortunately, the books and their connection to the Wars of the Roses are complex, so this will be a shorter summary than the other stories in this list.

The Wars of the Roses were fought over the English throne by cadet branches of the House of Plantagenet. The House of Lancaster (who inspired the Lannisters) and the House of York (House Stark) traded control of the country for three decades before the rise of Henry Tudor ended the conflict. Along the way, there were bloody battles, secrets, murdered advisors, palace intrigue, more than a few heads on pikes, and some poorly thought-out weddings. There was even a long-shot royal candidate from overseas with ties to a long-dead king (one of several historical counterparts of Martin’s Daenerys Targaryen). The conflict had many causes, though the difficulties caused by the reign of a “mad king,” Richard II, didn’t help matters.

Suffice it to say, it’s an expansive and exciting story. Martin’s version with the zombies and dragons is pretty great, too.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is the great American fairy tale. It centers on a girl named Dorothy who is whisked away to the Land of Oz by a tornado. She and her dog, Toto, are told that the best way to get home is to speak with the Wizard of Oz, who lives in the glorious Emerald City. Traveling there along the yellow brick road, she meets a Scarecrow who wants a brain, a Tin Woodman who wants a heart, and a Cowardly Lion in search of courage. After a few run-ins with wicked witches and a band of flying monkeys, Dorothy returns home.

While there are 40 books in the Oz canon, most people today only know the first novel. Even then, they are most likely familiar with it because of the famous 1939 film adaptation. To be fair, the film is pretty great.

The books can seem like just fun stories, as divorced from reality as it gets, but there may be a fair amount of actual history in them. Several commentators have argued that the original yarn is an allegory for American politics in the late 19th century. Most notably, several characters and events are proposed to stand in for people and concepts in the “free silver” debate and the election of 1896.

The question of how to back American money was the major political kerfuffle during the last decade of the 19th century. “Silverites” — who tended to be farmers, miners, and those in debt — argued that backing US currency with both gold and silver would lead to prosperity. Opposing them were “Goldbugs,” who wished to keep the currency backed by gold alone.

In modern terms, those supporting silver wanted a larger money supply and higher inflation. The hope was that this would ease the burdens of the indebted and increase revenues to mining states. Those opposed saw it as a quick way to destroy the financial system.

In Baum’s story, Dorothy, a stand-in for the American everyman from a farming state, is blown into Oz (as in “ounces”) by a tornado, an image often used at the time to represent political upheaval. Upon arrival, she acquires the silver slippers by accidentally killing the Wicked Witch of the East (they were changed to ruby in the film). This causes the “little people” of Munchkinland to rejoice. A good Witch who hails from the north ensures Dorothy that the silver slippers will protect her as she heads down the yellow brick road to the magical city of Oz — bimetallism manifest.

The Scarecrow is a stand-in for the American farmer; the rusting Tin Man represents the urban workers and the paralyzing effects of the 1893 depression. The Cowardly Lion represents William Jennings Bryan, a bold speaker who remained a pacifist. When the lion attacks the group upon their first encounter, he is defeated by the Tin Man — just as Bryan’s campaign was undone by his failure to gain the votes of industrial workers. However, they form a formidable team when they work together with the farmers.

When the group reaches the Emerald City — the same color as “greenback” dollar bills — they meet the Wizard of Oz. Like a sleazy 19th-century politician, he appears to each group member in a different form. He agrees to help them only in return for favors. Upon killing the Wicked Witch of the West, who desires the silver shoes to help her control the decaying western part of Oz, the Wizard is found to be a fraud. Luckily, a good Witch from the south knows the power of silver and reveals that the shoes can send Dorothy home.

This one is the most controversial of all the interpretations on this list. Many scholars argue that Baum did not intend for any reading of this kind.

However, later books in the series occasionally depict Oz as a quasi-socialist utopia. One novel shows that Oz has no currency, that the economy runs on mutual aid, that the workday has been cut, and that the workers need no harsh management to be productive. In another, a character traveling to another kingdom has no idea what money is. While this does not prove that Oz is based on American politics, it does suggest that Baum was more than willing to use the setting to explore political and economic ideas.