How art and design can rebuild a community

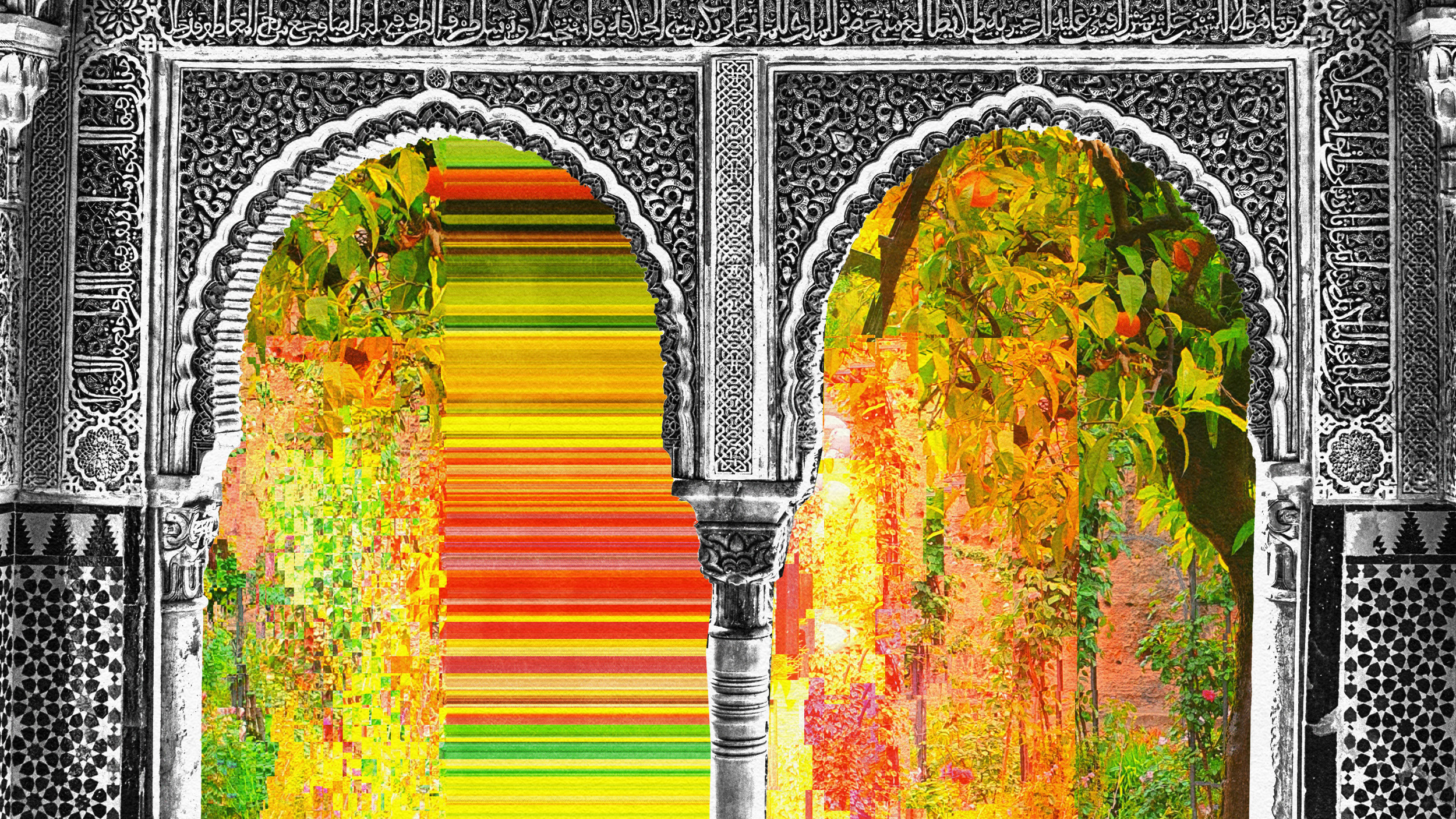

Credit: Memory Matrix

In the spring of 2016, a striking art installation was constructed outside MIT’s building E15.

The work consisted of 20,000 small green plexiglass squares, with intricate holes cut in each one, depicting vanished or endangered pieces of global cultural heritage, including buildings, monuments, and sculptures. Attached to fencing about 40 feet high, the squares collectively formed an image of the Arch of Triumph from Palmyra, Syria, an ancient treasure destroyed by fundamentalists in 2015.

Lit up at night or shimmering in daytime, this installation — the “Memory Matrix” — was a powerful reminder of the fragility of our cultural creations in the face of conflict and strife. But it also represented human resilience and the strength of collaboration: About 700 people helped construct it, including MIT community members from 11 different departments and programs, and participants from Egypt and Jordan.

“That project was amazing, because of the solidarity-building it created across campus and internationally,” says MIT Associate Professor Azra Akšamija, who created the idea for the installation.

Akšamija is an uncommonly versatile artist, architect, and scholar whose work explores cultural identity and conflict. Her own career exemplifies resilience: Akšamija experienced displacement as a Bosnian Muslim whose family left in the early 1990s to escape the war at home. Having spent much of her life in Austria, the United States, and Germany, her work frequently explores encounters between Islam and the West.

Among other distinctions, Akšamija was given the 2013 Aga Khan Award for Architecture for her design of a prayer space’s symbolic elements, at Austria’s first-ever Muslim cemetery, in Altach (the cemetery itself was designed by Bernardo Bader). Some of her best-known designs are wearable art, including her “Frontier Vest” from 2006, a garment that works as a jacket for refugees and can be transformed into a Jewish prayer shawl or an Islamic prayer rug. Akšamija has detailed many of her ideas in a 2015 book, “Mosque Manifesto — Propositions for Spaces of Coexistence.”

She has also been a program-builder at MIT, founding the Future Heritage Lab (FHL), which focuses on cultural preservation. At the Al Azraq Refugee Camp in Jordan, FHL members, along with their partners at German-Jordanian University, have helped Syrian refugees document their lives through photography, design, and poetry; the work was displayed at the 2017 Amman Design Week.

Over the past three years, camp residents, FHL members, and MIT students have developed a book about refugee inventions, which will be used in MIT’s first design studio-based online course, “Design and Scarcity” (co-taught by Akšamija and FHL program director Melina Philippou). The book will also be translated for the camp and the wider region.

The Al Azraq camp refugees, Akšamija says, “design artifacts that are partly utilitarian, but are about preserving human dignity and memory, and keeping the feeling of who you are. It’s powerful.”

“Making things since I could think”

Akšamija grew up in Sarajevo, now part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. One of her grandfathers was an accomplished architect who had studied in Prague and, she says, “brought Czech modernism back to Bosnia.” Design grabbed Akšamija’s interest from a young age.

“I have been making things since I could think about myself,” Akšamija says. “As a child I was completely obsessed with drawing and sculpture, which I would do for hours. Also, to get out of my piano lessons, I would make these plasticine sculptures and then display them on the piano, to distract the piano teacher.”

At the time, Sarajevo was part of the larger republic of Yugoslavia. But in 1992, after war broke out in the Balkans, Akšamija and her family moved to Germany, then Austria, to escape the conflict. As an undergraduate, Akšamija studied architecture at the Graz University of Technology. Still, she says, the university “had these awesome art classes,” and she wanted to incorporate art into her career.

Akšamija attended graduate school at Princeton University, receiving her MArch in 2004, while becoming active artistically; by 2004, her work had been displayed in high-profile institutions and exhibitions in Vienna, Valencia, Leipzig, and Liverpool. Joining MIT’s PhD program in the history and theory of architecture, Akšamija continued to create art; in addition to “Frontier Vest,” she produced noted works such as “Survival Mosque” (2005), a wearable and portable mosque equipped with a copy of the U.S. Constitution, earplugs (to block out the insults Muslims might hear), books, and more. Soon her work was exhibited in major art museums in London, New York, and Berlin.

Some of Akšamija’s projects from this period went in novel directions. With nine other artists and architects, Akšamija co-curated the “Lost Highway Expedition” in 2006, a trek in which 300 people walked the Highway of Brotherhood and Unity that connects the capitals of the former Yugoslavia.

“After the war I had thought, ‘I’m never going to Serbia again in my life,'” Akšamija says. However, for the trek, “we had events in cities and you had to find your own way, you had to make friends. And this is the way I went for the first time to the territories my country had the war with.” Though the project was challenging, she says, “It was important to start discussing difficult topics. It doesn’t mean they’re fully resolved. Unfortunately, there are still many people denying that genocide happened in Bosnia.”

For her dissertation, working with MIT professors Nasser Rabbat and Caroline Jones, as well as Harvard University’s András Riedlmayer, Akšamija looked at the systematic targeting of cultural heritage in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the 1992-95 war, examining how Bosnian Muslims restored mosques that had been destroyed.

“These buildings were attacked because nationalists wanted to revise history and alienate people to an extent that they would never want to live together in the future,” Akšamija says.

The questions driving her research apply anywhere, Akšamija says. “From the Balkans we can learn important lessons about how we live in spaces of fragmented commons. When that falls apart, how do you reconnect? What kinds of cultural institutions do we need to bridge divides and hold governments accountable? It is relevant globally. Who has the right to write their history, to be visible in public space, and who decides those things?”

After joining the MIT faculty, Akšamija earned tenure in 2019.

Becoming yourself

At MIT, Akšamija has found it gratifying to see students gravitate to her classes, to projects like “Memory Matrix,” and to the Future Heritage Lab.

“MIT students care,” Akšamija says. “They really want to do something to contribute to this world. This place is so inspiring.”

At the same time, she notes, the Institute can be an intense academic setting, and instructors need to help sustain the sheer enjoyment of learning.

“You [can] lose sight of why you started doing things and what initially drew you to them, and it can be overwhelming,” Akšamija says. “You see it with students. I like to create joy in things, especially in classes. That’s why it’s so amazing to teach here, because the students are so full of enthusiasm and joy. But also sometimes anxiety, and I think we all have responsibility here as teachers to take care of that. It’s not about students performing for someone else, but becoming better versions of themselves.”

Akšamija calls the current direction of her research “Performative Preservation.” This is an approach to cultural preservation that uses “methods of contemporary arts and participatory art.” She emphasizes that participation and co-creation are crucial to cultural restoration; physical structures can be rebuilt, but they will lack meaning without community involvement.

Her work is now on view at the Gallery for Contemporary Art, in Leipzig, Germany, and at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, with a new work slated for the 17th International Architecture Exhibition for the Venice Biennale, in May 2021. Curated by Hashim Sarkis, dean of MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning, the Biennale’s theme is “How Will We Live Together?” Akšamija’s project, “Silk Road Works,” a symbolic construction site for a pluralist society, will be part of a section at the Arsenale titled, “Among Diverse Beings.”

As always, Akšamija hopes for a thoughtful response from her audience, without knowing exactly what that will be.

“When you work in public space, it’s not about finding a consensus, where we all have the same opinion and are happily living together,” Akšamija says. “It’s about accepting and coming to terms with conflicting attitudes and ideas, and making space for them.”

Reprinted with permission of MIT News. Read the original article.