“Crazy Rich Asians” director Jon Chu on the American Dream and silencing your inner critic

- Growing up Asian-American, director Jon Chu juggled two identities.

- At film school, his personal preferences clashed with faculty and peers.

- In his 2024 memoir, Viewfinder, Chu reflects on his unusual upbringing, his ever-changing conception of the American Dream, and the challenges he faced chasing that dream as a first-generation Asian American.

In 1964, a steamship passed underneath the Golden Gate Bridge and entered the San Francisco harbor. Aboard was Lawrence Chu, a young man from Sichuan who, like so many Chinese immigrants, came to the United States in search of an American Dream. Three years later, his future wife, Ruth Ho, left her native Taiwan for the same reason.

The ever-elusive concept of the American Dream means something different for every person. For the Chus, it took the shape of Chef Chu’s, a thriving Chinese restaurant in California’s Los Altos that remains a community favorite to this day. Along for the ride came five children, the very youngest of which, a creative and self-described “weirdo” named Jon, went on to pursue one of the more archetypal versions of the American Dream, becoming an accomplished filmmaker and director of such movies as Crazy Rich Asians, Now You See Me 2, In the Heights, and Wicked.

In his 2024 memoir, Viewfinder, Jon Chu reflects on his unusual upbringing, his ever-changing conception of the American Dream, and the challenges he faced chasing that dream as a first-generation Asian American, including the push-and-pull between fitting in, following your own path, and managing your inner critic as a budding artist.

Finding community

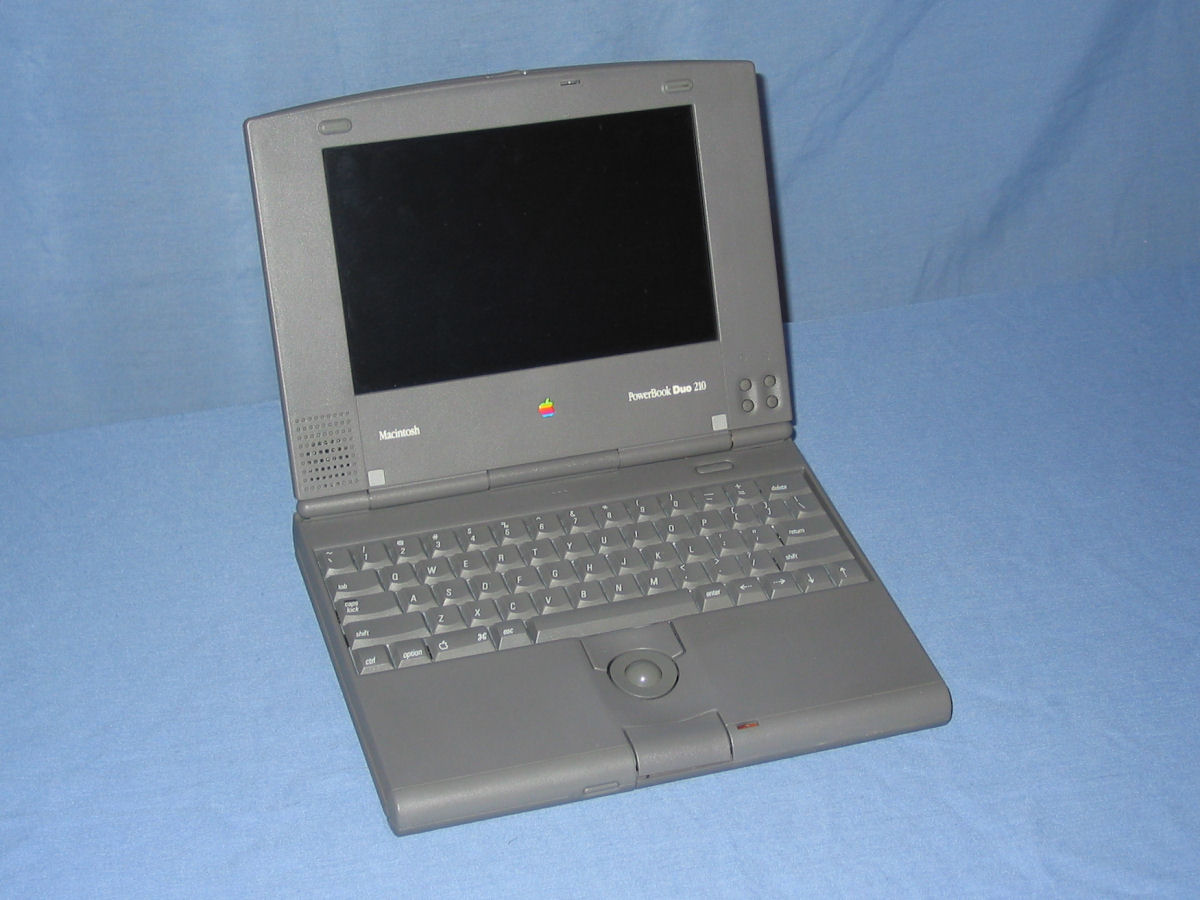

Viewfinder describes a happy, borderline idyllic childhood, with Chu’s parents encouraging his every passion and interest, from drawing to tapdancing and — following his surprisingly tear-jerking documentation of a family trip to Boston — filmmaking. Growing up on the edge of Silicon Valley during the 80s and 90s, he counted Steve Jobs among his heroes. Jobs used to dine at Chef Chu’s from time to time, as did other tech disruptors. Taking to the Chu’s, they occasionally brought along gadgets for Jon, who in turn taught himself to work with AV mixing machines and PowerBook Duos long before these went mainstream.

“For more than a decade, I watched as Silicon Valley products and systems opened up new possibilities for Hollywood’s creators,” Chu writes in Viewfinder. “When I directed Crazy Rich Asians, I had the sensation that I was riding that wave, drawing on the strengths of both places, making good on so much of the promise I’d foreseen in my childhood.”

Growing up in Los Altos had another, equally valuable benefit. Supported by the city’s relatively large Asian American community, Chu didn’t see himself as part of a minority and — as a result — readily internalized the belief that anything was possible. “I didn’t have to deal with my own cultural identity crisis,” he tells Big Think. “I was just a kid. I could dream and convince myself the barriers were low. People knew and loved our family, and I felt free.”

It wasn’t until he started going to film school at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, where the Asian American community on campus was much smaller and fractured than at home, that he realized that “no one is promised a community — that you have to pursue and actually participate in one.”

Fitting in

Surprisingly, Chu’s jumpstart with video and editing software didn’t put him ahead of his film school peers. “The teachers expected to use yesterday’s technology: everything analog, everything manual,” he writes in Viewfinder.

“When they talked about splicing footage,” he tells Big Think, “they meant actually, physically splicing it. We all had little scars on our fingers because of the cutting.”

Chu clashed with USC faculty over not only equipment but also filmmaking style.

“My taste was different from others,” he says. “I love movies that inspire, have love, and are earnest. At the time, earnestness was treated as poison, because people liked art that was biting and sarcastic. Everything needed to be a ‘hot take.’ Everyone wanted dark things from me, and they weren’t necessarily wrong — because there is indeed a naiveté to believing in the simplicity of love, the movie version of love, of Wonder and Happy Endings.”

While there’s value in listening to your own guts over someone else’s, it can also close you off to different perspectives. At film school, many a prideful student risks falling into a state of arrested development because they refuse to learn from others. In Los Altos, Chu’s parents had preached a kind of middle way between fitting in and standing out — between dressing and sounding “American” and acting as ambassadors of their Chinese heritage. At USC, this middle way helped Chu grow without losing touch with his unique voice.

“I learned I didn’t have to turn into these other filmmakers. They have amazing work, and I don’t have to chase that. Still, I knew that I had to experience life outside Los Altos and go through the darkness. I knew that, if I could hold on to my optimism, to my dreaming, I would have a clearer idea of how to communicate that to an audience.”

– Jon Chu

Just as Chu balanced learning from others while staying true to his own vision and identity, so too did he learn to deal with criticism — from others, and from himself. Here, the can-do attitude he inherited from his parents came in handy.

“Everybody seemed to doubt me,” he writes in Viewfinder, recalling one of his first directing gigs. “Sometimes even I doubted me. But I had to keep showing up every day, acting as if I had it all under control.”

The commercial success of his later films, especially Crazy Rich Asians, gradually dulled the sting of harsh reviews; the applause of millions of viewers drowned out the boos of a handful of critics. But while Chu learned to shake off criticism from others, he remained critical of his own work, always striving to improve and do the best he can:

“It’s sleepless nights of doubting whether you’ve made something good. No matter how long you’ve been doing a job or how good people say you are, you need to care as if you’ve never done it before. You need to care as much as my dad does every time he puts on his chef’s whites.”

Now, at a time when technology — courtesy of Silicon Valley — has turned Hollywood from an industry of auteurs into a data and algorithm-driven assembly line that specializes in creating mass-marketable blockbusters devoid of personal touch, Chu’s movies stand out for being both intimate and big-budget. Rather than adapting Kevin Kwan’s bestseller beat for beat, imparting little of himself, Chu imbued Crazy Rich Asians with scenes plucked from his own upbringing, including memories of his great-grandmother.

“As the baby of the family, I helped her fold the dumplings,” he writes in Viewfinder. “My folds were always pretty terrible, especially compared with Bu Bu’s; her hands moved like a jazz musician’s. My memory of those simple, joyful afternoons with her is the reason I put a dumpling folding scene in [the movie].”

Chasing the American Dream

Crazy Rich Asians, which follows two New York University professors who travel to Singapore for the wedding of a mutual friend, deals with a theme that also applies to Chu’s own life: the complicated relationship Asian Americans have with the countries their parents and grandparents came from, and the United States, the country in which they themselves were born and raised.

In pursuit of their own interpretation of the American Dream, Chu’s parents — particularly his mother — sought to acquaint their children with European high culture, prioritizing English over Mandarin and cultivating a love for Beethoven and Brahms (never mind that you’d be hard-pressed to find many European or American children nowadays who know who these people are). They gave their children American names like Christina, Jennifer, and Howard, and dressed them to look — in Chu’s words — “like Asian Kennedys.”

They also taught their children to “never complain.”

“I heard the terrible things that my parents had to put up with,” Chu writes in Viewfinder. “It made me defensive — angry even. But my parents didn’t get mad. They didn’t fight back. Instead they told me to be calm. The way they saw it, we might be the first Chinese family these customers have ever known. That made us ambassadors for all the other Chinese families out there. If we stayed poised, if we showed class, maybe those obnoxious customers would see that a Chinese family could be anything. And then maybe they’d treat the next family better than they’d treated ours.”

It’s useful advice, whether you’re a restaurant owner or an aspiring director moving up Hollywood’s labyrinthine chain of command. But, as Chu came to recognize, it also has its limits. “Now that I’m in a position of power,” he says, “I cannot be silent. I have a responsibility.”

Speaking out against mistreatment and injustice — in the real world of Crazy Rich Asians and In the Heights and the fantastical world of Oz in Wicked, which reimagines the Witch of the West as misunderstood — initially felt like a betrayal of his parents’ tried and tested life philosophy. However, the positive reception of his work, let alone the opportunities it has created for Asian American talent, gradually changed that.

“Maybe it also had something to do with having children,” he says, “and wondering what I wanted to teach them. Doing different for the next generation and trying to prepare the landscape for them in the best way possible — that’s when I finally felt like I had found my voice.”