4 literary masterpieces whose titles hide a deeper meaning

- Book titles play a crucial role in capturing and conveying the essence of the text, often encapsulating its central themes, narrative, or message.

- They can be laden with double meanings, influenced by linguistic nuances, or borrowed from other texts to create layers of intertextuality.

- Understanding the deeper meaning behind a book’s title can leave you with a different impression of the story.

F. Scott Fitzgerald completed his most famous novel, The Great Gatsby, in a little over a year. This was unusual for him, as he was a famously slow writer. Enslaved by his own perfectionism, which originated from insecurity and worsened as a result of alcohol abuse, he could spend days mulling over a single sentence. “I cannot let it go out unless it has the very best I’m capable of,” he once told his editor, “or even, as I feel sometimes, something better than I’m capable of.”

Gatsby seems to have been written in a kind of flow state, with its story and larger-than-life characters practically writing themselves. The only thing Fitzgerald really struggled with was the title. Early contenders included Among Ash-Heaps and Millionaires, On the Road to West Egg, Under the Red, White, and Blue, and The High-Bouncing Lover. He himself leaned toward Trimalchio, which his wife Zelda vetoed. He then considered Gold-Hatted Gatsby before finally settling on The Great Gatsby.

To the outside observer, Fitzgerald’s indecisiveness may seem pedantic. But the author knew that titles are anything but trivial. Aside from luring in readers, a good title captures the essence of and gives meaning to the entire text. That explains Fitzgerald’s fondness of Trimalchio, named after the character from Roman literature whose journey from a former slave to a self-made merchant mirrors Gatsby’s own rags-to-riches story. A title like The Great Gatsby accomplishes the same thing while also adding a dash of irony and ambiguity.

Book titles come in all shapes and sizes. Some are descriptive (Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man), others poetic (The Unbearable Lightness of Being). Some are straightforward (Jane Eyre, Don Quixote, The Brothers Karamazov) while others still contain a hidden, deeper meaning that — once revealed — can drastically alter the impression a text leaves on its readers. Below are four classic works of literature that accomplish just that.

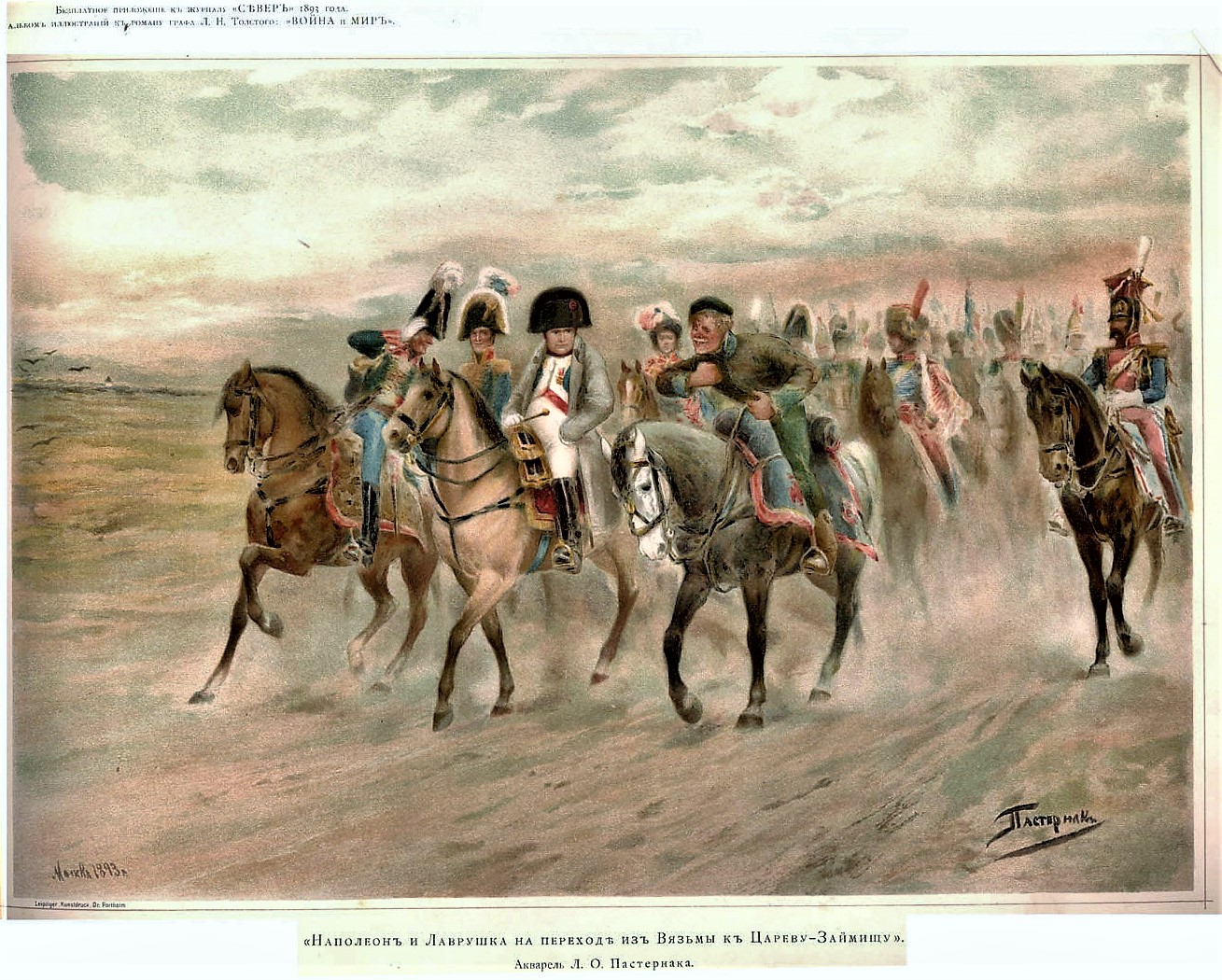

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

The title of Leo Tolstoy’s 1,200-page magnum opus, War and Peace, which follows a group of Russian nobles in the Napoleonic Wars, leaves little room for the imagination. However, this is not the case in the original, as the Russian word for “peace” (mir) also means “world.” As a result, Voina i mir could be translated as “war and world” or, more specifically, “war and society,” calling into question the dichotomy of conflict and cooperation that so many Western critics have used to make sense of the novel.

Tolstoy’s authorial intent has long been a subject of debate. People who believe the title has been misinterpreted blame the Bolsheviks, whose tinkering with the Russian alphabet caused words like mipъ, meaning “society,” to fall out of use. People who believe it was always supposed to be War and Peace note that Tolstoy, who was multilingual, did not object to foreign translations of his work, such as the French translation: La guerre et la paix. In all likelihood, the author must have been aware and accepting of both interpretations.

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

Many titles that seem original are in fact borrowed from other texts, often monumental works from the distant past. This is true for The Sun Also Rises, a phrase Ernest Hemingway found in Ecclesiastes 1:5-11, and it is true for Aldous Huxley’s dystopian novel Brave New World, originating from the following line of William Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, spoken by the character of Miranda in Act V Scene I: “How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world / That has such people in ‘t!”

Miranda grew up in isolation on an island with her father, Prospero. Her words express her excitement at finally meeting other people, but they also betray her naïve optimism about the nature of mankind. Huxley reflects this optimism in his protagonist, John, a savage who is taken from a reservation and introduced to a society that at first glance seems utopian, but is actually ruled by an authoritarian regime that classifies its subjects at birth and forces them to take a libido-repressing drug called “soma.”

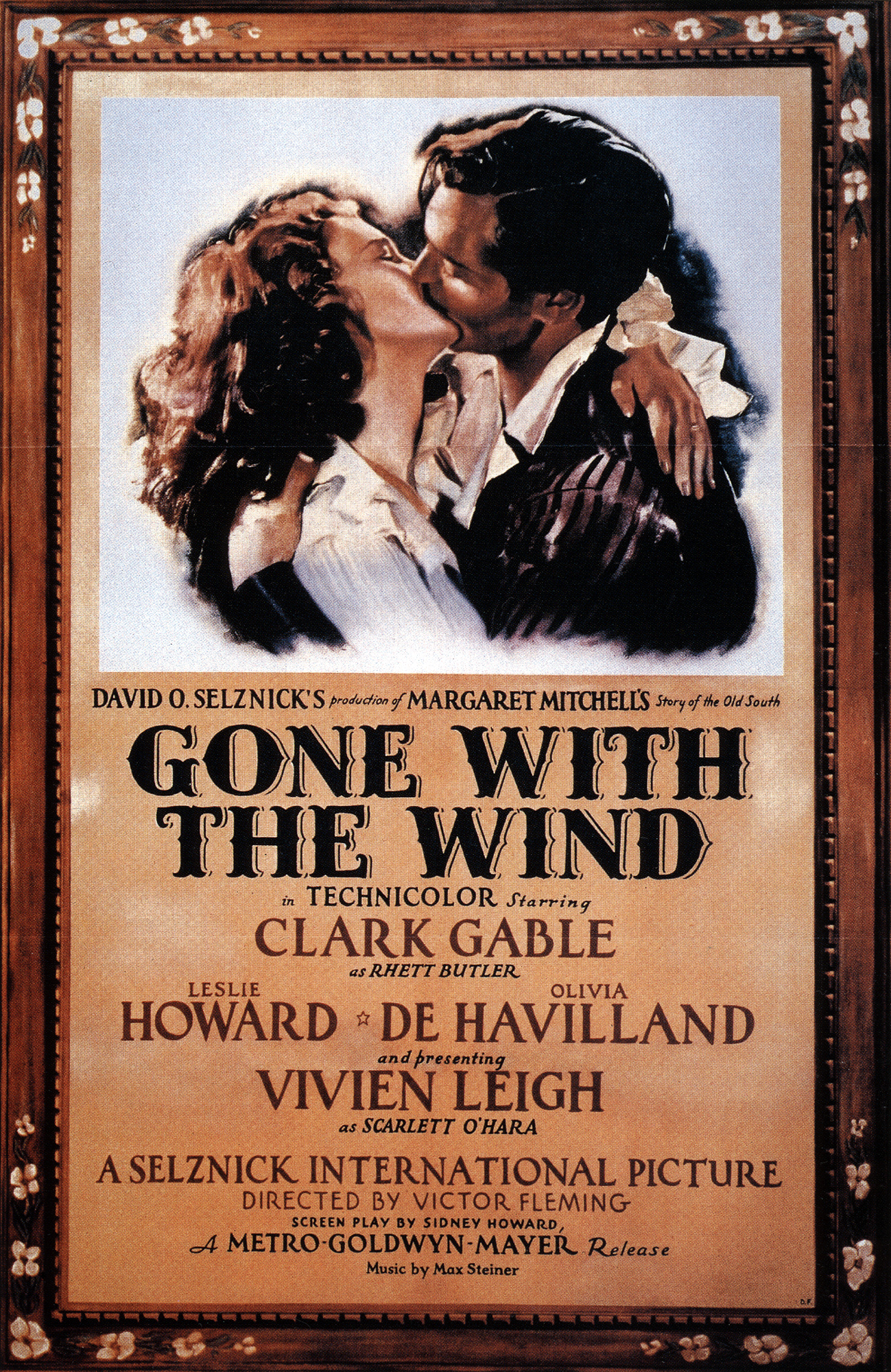

Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell

Analogous to War and Peace in scale and scope, Gone with the Wind follows the daughter of a plantation owner who struggles to regain her family’s wealth and status in the aftermath of the American Civil War. The novel, which has been alternatively praised and criticized for the way it romanticizes the slave-owning South, went through a number of working titles, including Tomorrow is Another Day, Bugles Sang True, and Not in Our Stars (not to be confused with John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars).

Gone with the Wind evokes nostalgia for a way of life that disappeared following Sherman’s March Through Georgia, a military campaign that aimed to destroy the southern state’s infrastructure and resources. The author took the phrase from Ernest Dowson’s 1894 Victorian poem Non Sum Qualis Eram Bonae Sub Regno Cynarae, itself taken from a poem by Horace: “I am not as I was under the reign of the good Cynara,” the Cynara in question being the Roman poet’s former mistress.

Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov

Each of the aforementioned titles condenses the message or argument of their respective texts into a few words, and Mikhail Bulgakov’s Heart of a Dog is no exception. Written in 1925 but censored in the Soviet Union until 1987, the story is about a surgeon who grafts a human pituitary gland and testicles onto a stray dog, causing it to turn from an animal into a human who behaves nothing like the way his creator intended him to behave, shunning personal hygiene and later accepting a job through the Communist Party.

In addition to criticizing eugenics — a pseudoscience that interested the Kremlin and would be taken to its extreme by the Nazis in World War II — Heart of a Dog parodies the notion that the USSR could transform its citizens from bourgeois citizens concerned only with private interests into a new species of human: the Soviet Man or Homo Sovieticus, who conforms to government control and works tirelessly for the good of the collective. Just as the surgeon’s experiment fails, so does the Kremlin’s.