5 great books with glaring plot holes

- Some authors meticulously plan their books while others just see how things progress, but both suffer from the same problem: the collective judgment of millions.

- Here we look at plot holes in five great books, from the Harry Potter series to a classic detective story by Raymond Chandler.

- Perhaps the best attitude to take to plot holes is to take a leaf from Raymond Chandler and say, “Damned if I know.”

There are two kinds of fiction writers. First, some meticulously plan their book, page by page. They ask, “What information do I need to reveal?” and “Who says what to whom?” They know exactly what happens at the end. These writers often draw intricate, interweaving diagrams that look more like schematics than novels. J.K. Rowling, Joseph Heller, and Agatha Christie are all famous examples of this type of author. The second type is the “let’s see where this goes” kind of writer. They have an idea and a vague direction in mind, but let their characters and plots dance away as they feel. Stephen King is one such writer. He once wrote, “Outlines are the last resource of bad fiction writers who wish to God they were writing masters’ theses.” But then again, he is Stephen King.

Whatever approach they take, both types of writers can fall prey to the same problem: plot holes. Although plot holes have always existed in stories, the internet — where millions of people with their beady, forensic eyes can crowd-source their pedantry to unpick and unravel every little character and plot device — has brought to light countless narrative discrepancies, both big and small. Here, we look at some famous examples. (There will, inevitably, be spoilers.)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban — Time-Turner

Time travel is always a messy plot device and suffers from two problems. On the one hand, you have a plot full of contradictions and paradoxes. For example, in the famous “grandfather paradox,” altering anything in the past (such as meeting your grandfather when he was a boy) should radically change the present you came from originally. On the other hand, if you want to make time travel seem plausible in your story, you have to have a narrative so heavily laden with technical exposition that it weighs down the entertainment factor.

J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series falls prey to the first problem. In Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Professor McGonagall gives Hermione a “Time-Turner” so she can go back in time to attend classes. Later, Harry and the team use the Time-Turner to save Sirius Black and Buckbeak, the hippogriff. It’s all very entertaining. But, then, the Time-Turner is forgotten. Even if we accept that Harry couldn’t just go back and kill baby Voldemort, all manner of evil could still have been prevented. Why didn’t Dumbledore, the most powerful wizard in the world, use it to go back and save Remus Lupin, Cedric Diggory, or Dobby, the house elf? Weirdly, this obvious strategy is never exploited.

War of the Worlds — Microbes

H.G. Wells’ novel, War of the Worlds, is the archetypal alien invasion story. After Martians land on Earth, with their heat rays and giant tripod war machines, they quickly set about taking over the world. Yet, eventually, the Martians fall prey to Earth’s microbes: the bacteria and viruses we’ve grown resistant to.

The problem is that we’re led to believe these Martians are hugely intelligent, highly advanced, and have been monitoring Earth for a long time. Humans have known about foreign microbes for centuries, and our astronauts take great precautions when coming back home. If a species as lacking in heat rays as us can predict a microbial attack, why couldn’t the Martians?

Twilight — Blood

In the Twilight universe, as with most vampire lore, vampires go crazy when they smell or see blood. They go into a bloodthirsty frenzy, held back by force or intense strength of will. Jasper, a vampire, is the worst such case, and the books feature him often going feral with bloodlust. Yet, in the high school he attends, roughly 25% of the women there will be bleeding. The vampires should be in a constant state of hungry madness. It’s often the case that, in a writer’s world, women don’t menstruate.

The Hobbit — Middle-earth

When J.R.R. Tolkien wrote The Hobbit, he intended it as a fun adventure story for children. It was, essentially, the collected narrative of all the fairy stories he’d told his kids over the years. He thought it was a small thing – a side project to be forgotten. His publishing house, George Allen & Unwin, was convinced to publish it because Stanley Unwin’s son, Rayner, liked it. Rayner wrote, with faint praise, “It is good and should appeal to all children between the ages of 5 and 9.”

It appealed to many more people than that, and most of them were over nine years old. Tolkien was persuaded to work on a sequel, but this time to target adults. It took him about 12 years to write The Lord of the Rings trilogy. In that time, he invented an entire Elvish language, along with an encyclopedia’s worth of Middle-earth history. The problem is that Tolkien had never intended The Hobbit to fit into this vast, complicated lore. It was a bedtime story. The result is that The Hobbit has all sorts of problems. For instance, Gandalf is a bumbling, half-decent wizard, not the demi-god he later becomes. Gollum gives up the most powerful ring in the Universe over a riddle game. It takes the company far longer to get to Rivendell in The Hobbit than in The Lord of the Rings.

Tolkien acknowledged some of this and had a clever workaround: The Hobbit was written by Bilbo. It was not an accurate account but an interpretation and (mis)representation of the facts. Tolkien wasn’t an Oxford professor for nothing.

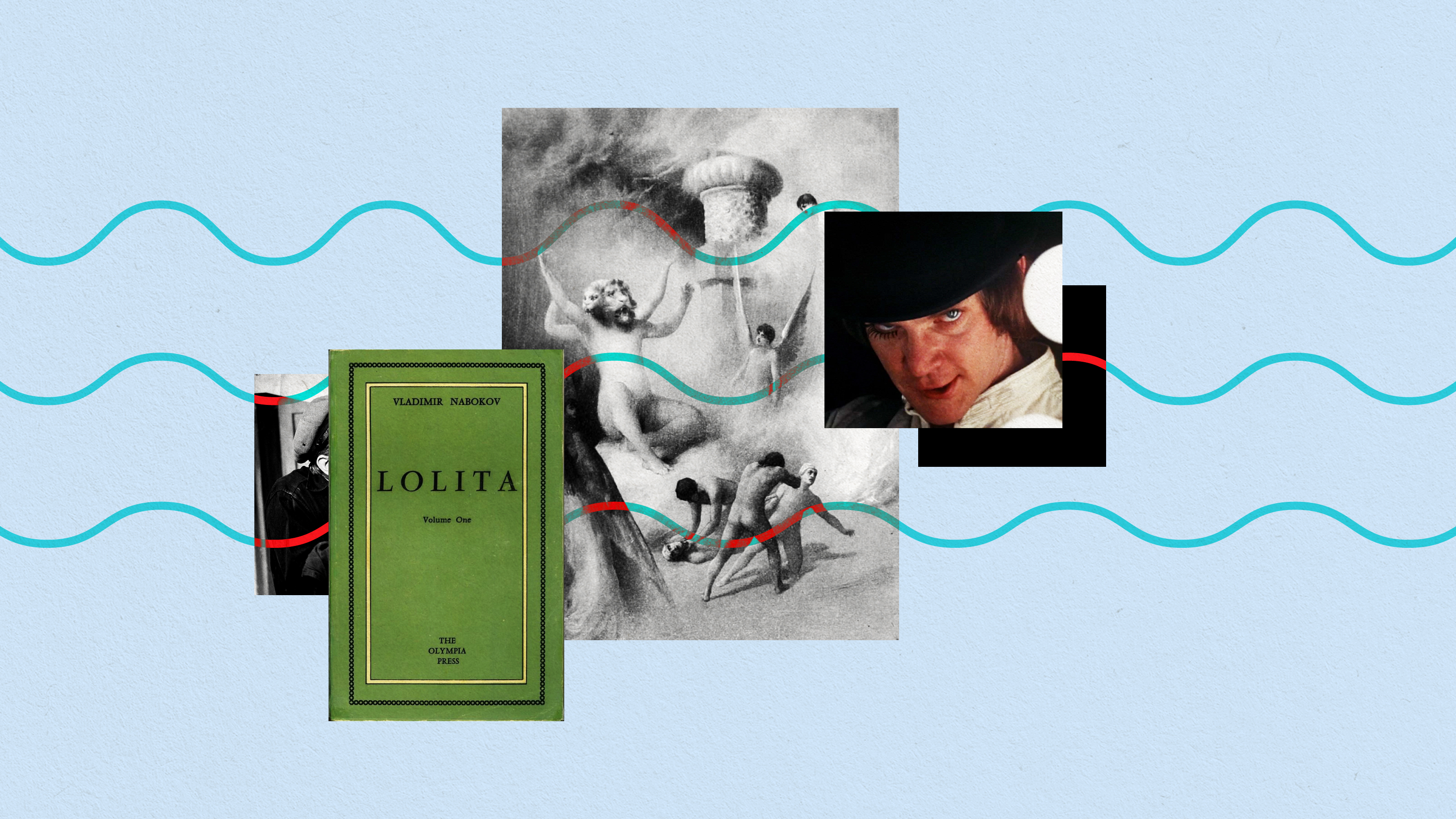

Raymond Chandler — The unsolved murder

Our last entry is perhaps more of a famous, decades-long gripe than it is a plot hole — but having a murder go unsolved in a detective story is arguably a worthy gripe.

In Raymond Chandler’s famous novel, The Big Sleep, we learn that a chauffeur, Owen Taylor, is found dead in his car, which has been dumped in a lake. Marlowe investigates his death, but he can’t find the killer. There are many suspects and dodgy characters, but we never find out who killed him. Given that Chandler was writing detective “whodunit” novels, this irritated, and still irritates, a lot of readers.

When the filmmakers came to turn The Big Sleep into a Hollywood success, they fumbled and staggered over this problem. They sent Chandler a telegram to ask him who killed Owen Taylor. Chandler’s response? “Damned if I know.” That’s as good an attitude as any to take about plot holes.