The healing power of love? Pair-bonding might prevent cancer in mice

- The widowhood effect describes how someone becomes more likely to die shortly after the death of their spouse.

- In the new study, the results of rodent experiments suggest the existence of a biological mechanism by which pair-bonding changes the gene expression of cancer cells.

- The results could illuminate new avenues for cancer treatments, but they also raise concerns over the accuracy of medical research involving rodents.

Does love possess healing powers? The question might seem naïve, but it is one physicians have contemplated in various forms for nearly two millennia.

The idea that love heals might have originated from its inverse: sadness harms. In the 2nd century, the Greek physician Aelius Galenus proposed that melancholy and depression can cause cancer. Other physicians would go on to repeat this hypothesis, including Arab doctors in the 9th century, French physicians in the 17th century, and the 20th century American psychologist Elida Evans, whose 1926 review of 100 cancer patients found that all had lost important emotional relationships prior to developing the disease.

The results of a new study suggest that loving relationships do indeed protect against cancer. What’s more, this protection does not seem to stem from the behavioral or lifestyle traits of couples but rather from a biological mechanism that directly inhibits tumor growth.

The widowhood effect

Published in the journal eLife, the study used mice to explore the “widowhood effect,” a well-documented phenomenon in which someone becomes more likely to die shortly after the death of their spouse.

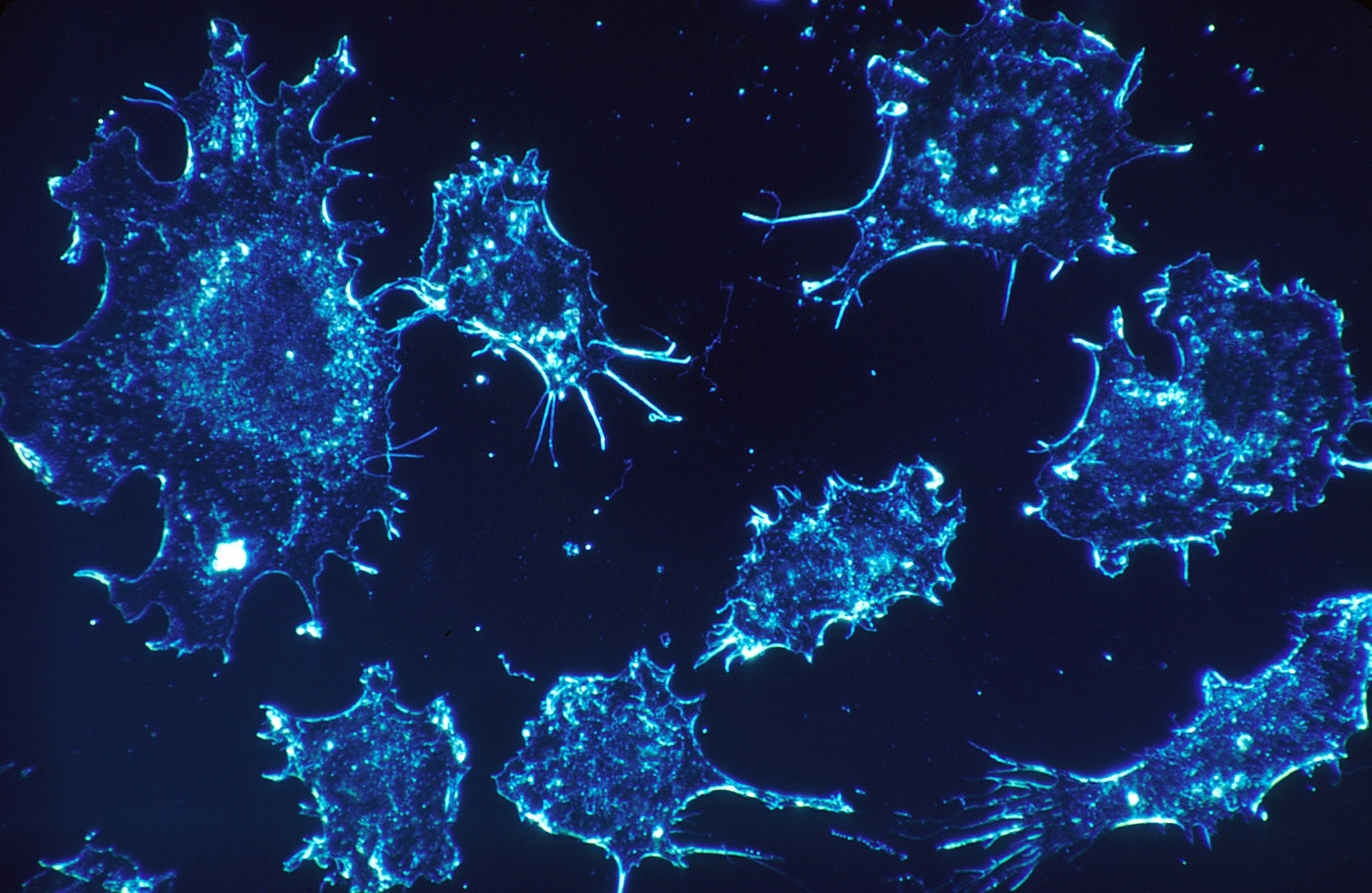

The researchers extracted blood sera from two groups of mice. One group comprised monogamous mice that had bonded for one year; the other had their pair bonds disrupted after 12 months. The researchers then grew human lung cancer cells in sera from both groups. In the blood of mice with disrupted pair bonds, cancer cells grew larger, took on shapes linked to an increased risk of cancer, and showed gene activity that suggested an increased ability to spread.

The researchers conducted a second experiment within live mice. They extracted lung cancer cells from pair-bonded and pair-disrupted mice and implanted the cells into virgin mice with weakened immune systems. The cancer cells from pair-disrupted mice grew more effectively in the virgin rodents, suggesting that “the protective effects of pair bonding persist even after removal from the original mouse.”

Love heals all wounds

Overall, the results suggest that social activity — particularly pair bonding, e.g. positive and intimate relationships — can change the gene expression and growth of tumors. But how? It is not exactly clear, but the authors of an article published in Trends in Molecular Medicine proposed a three-step process:

- Social information is encoded in a neural signal.

- The neural signal directly or indirectly induces the release of some sort of immune-related factor into the bloodstream.

- The humoral factor binds to a receptor on cancer cells that induces changes in gene expression.

If correct, this process could change how researchers think about the widowhood effect, which is often explained by lifestyle changes, hormone-induced changes to the heart, or disregarded as coincidence. The new model could establish a biological basis for the effect, one that illuminates avenues for novel cancer treatments in humans — if the same processes are observed in people.

The researchers wrote:

“…cancers at widowhood represent a distinct pathological entity that may deserve targeted therapeutic strategies, which should take into consideration social interactions. Thus, preventive measures could be developed to mitigate such pro-oncogenic effects in individuals at bereavement.”

It’s hard to say what those treatments would look like. After all, even though research has linked pair-bonding to numerous health benefits — longer lifespan, lower blood pressure, improved mental health — doctors cannot prescribe love. Pharmacological treatments would probably need to do the job.

The researchers also noted that the results raise concerns over medical studies that utilize animal models: given that the health of mice may partly depend on the rodents’ own relationships, it is possible that some studies failed to “accurately capture the whole spectrum of the tumorigenic process and the associated host-derived factors.”