Why does music numb physical pain? Scientists uncover clues.

- For over 80 years, music has been known to have a broad range of pain-numbing properties; however, it is unclear how this happens.

- A team of neuroscientists discovered that only soft sounds — about 5 decibels higher than ambient noise — reduce pain in mice.

- The researchers also uncovered an unusual neural connection between the brain’s auditory and pain-processing regions.

In 1960, a Boston-based dentist named Wallace J. Gardner reported using an unusual technique to control his patients’ pain. Instead of utilizing nitrous oxide or injecting a local anesthetic, Gardner handed his patients a pair of headphones and a small volume control box before proceeding to yank out their rotten teeth. Gardner claimed that he, as well as other dentists around the country, had performed 5000 dental procedures using music and noise to induce analgesic effects, and 90% of those procedures did not require any additional anesthetic.

Gardner hypothesized that the brain’s auditory system impinges upon the pain system when listening to pleasant music. Still, it was unclear how this happens. More than 60 years after Gardner’s report, neuroscientists have uncovered two clues about how sound blocks pain: the volume of the music and a surprising circuit between the sound- and pain-processing regions of the brain.

Soft music reduces pain in mice

Since Gardner’s report, scientists and physicians have discovered that music and sound have a broad range of pain-numbing properties. For example, they can help soothe acute pain, such as that which occurs during surgery and childbirth, and chronic pain from long-term ailments, such as cancer. Although it is clear that sound can reduce pain, a team of Chinese and American neuroscientists wanted to determine how sound reduces pain, as it could reveal new strategies for treating pain. However, this requires manipulating neurocircuitry, which is generally frowned upon in humans.

So, the team chose to use mice in their study. While it seems like an obvious solution, using rodents to study how music reduces pain is a challenge, most notably because it is unknown how animals perceive music. As such, the researchers first needed to determine whether music would elicit analgesic effects in mice at all.

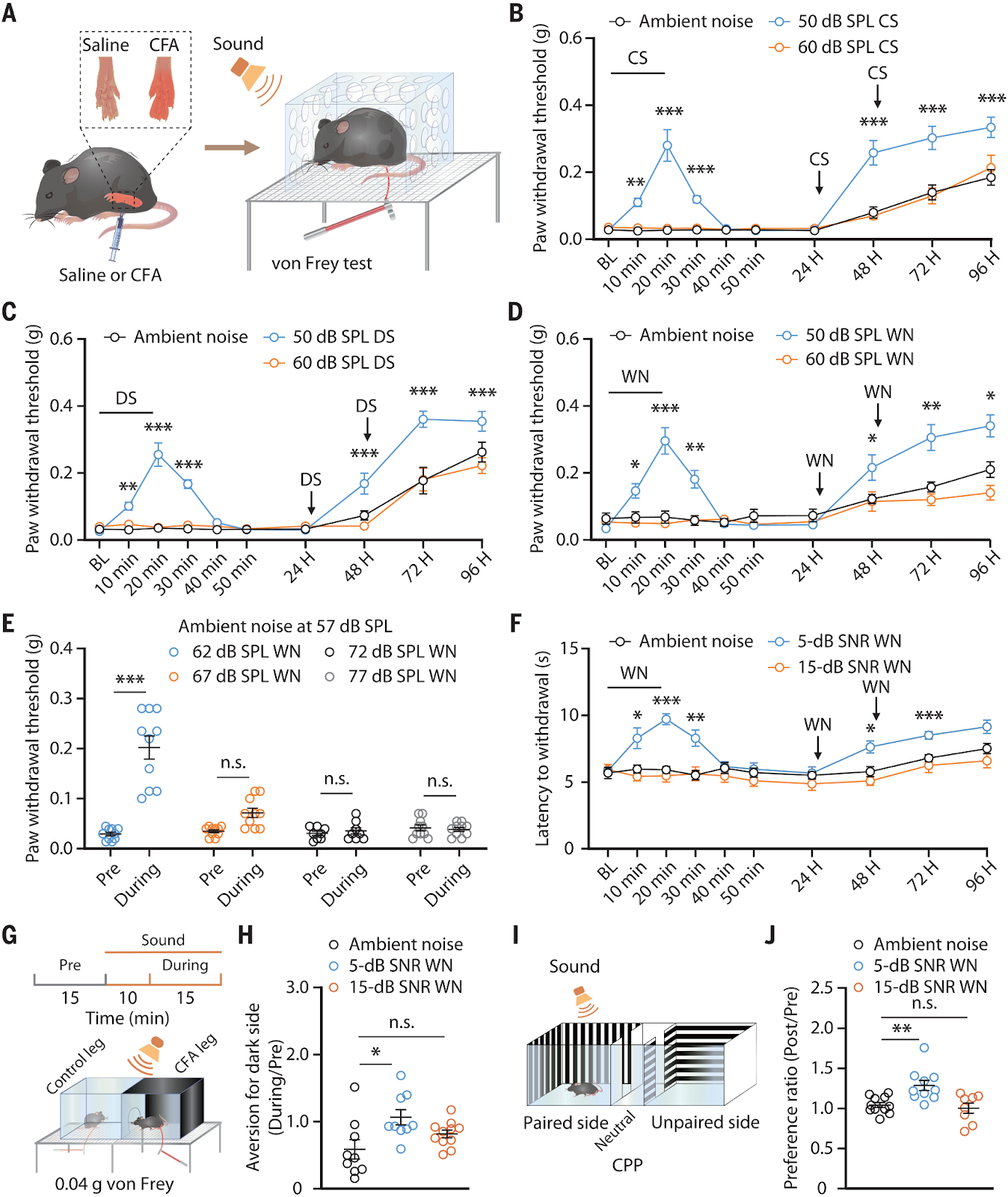

They played three types of sound for mice with inflammatory pain: a piece of symphonic music (Bach’s Réjouissance), an unpleasant remix of Bach’s symphony, and white noise. The researchers found that all three sounds reduced pain sensitivity, but only if the sounds were played at 50 dB (the volume of a quiet conversation in a library). This finding was unexpected.

Dental procedures are noisy. Music played at 50 dB would be drowned out by the buzzing of drills, the clammer of metal tools against a metal tray, and the sloppy suction of the saliva ejector. The researchers were conducting their study in a relatively quiet laboratory (the ambient noise was about 45 dB). They suspected that the volume of the music was less important than the difference between the music and the volume of ambient noises.

So, they raised the room’s ambient noise to 57 dB and found that pain sensitivity decreased when music played at 62 dB. They lowered the ambient volume to 30 dB, and only music played at 35 dB produced the pain reduction effects. Sound seemed to reduce pain only if played slightly louder than the ambient noise.

An unusual connection between the auditory and pain regions of the brain

Having shown that sounds can reduce pain in mice, the researchers began their search for the elusive pain-numbing neurocircuitry. By injecting a tracking dye into the mice’s auditory cortex (the brain region that receives and processes information about sound), the team of researchers revealed a route that connected the auditory cortex to the thalamus, a relay station for processing sensory signals such as sound, taste, and pain. All sensory organs have a direct connection to the thalamus. This connection, however, was unusual.

One would expect that hearing music would increase the neural communication between the auditory cortex and thalamus. However, the newly discovered neural connection stopped transmitting information when low-volume music played. To confirm this neurocircuitry was involved in suppressing pain, the team blocked it from activating. As a result, the mice appeared to feel less pain, even without music. The researchers concluded that low-volume sounds blunted direct communications between the auditory cortex and thalamus, tamping down on pain-processing in the thalamus.

The researchers acknowledged that neural mechanisms underlying music-induced analgesia in humans are doubtlessly more complicated than those in mice. However, identifying the connections between the auditory cortex and pain-processing regions could expedite the study of music-induced analgesia. In the future, these findings could spur the development of alternative interventions for treating pain.