New obesity treatments could reshape the world

- Nearly 1 billion people were obese in 2020, with a projection of 1.9 billion by 2035.

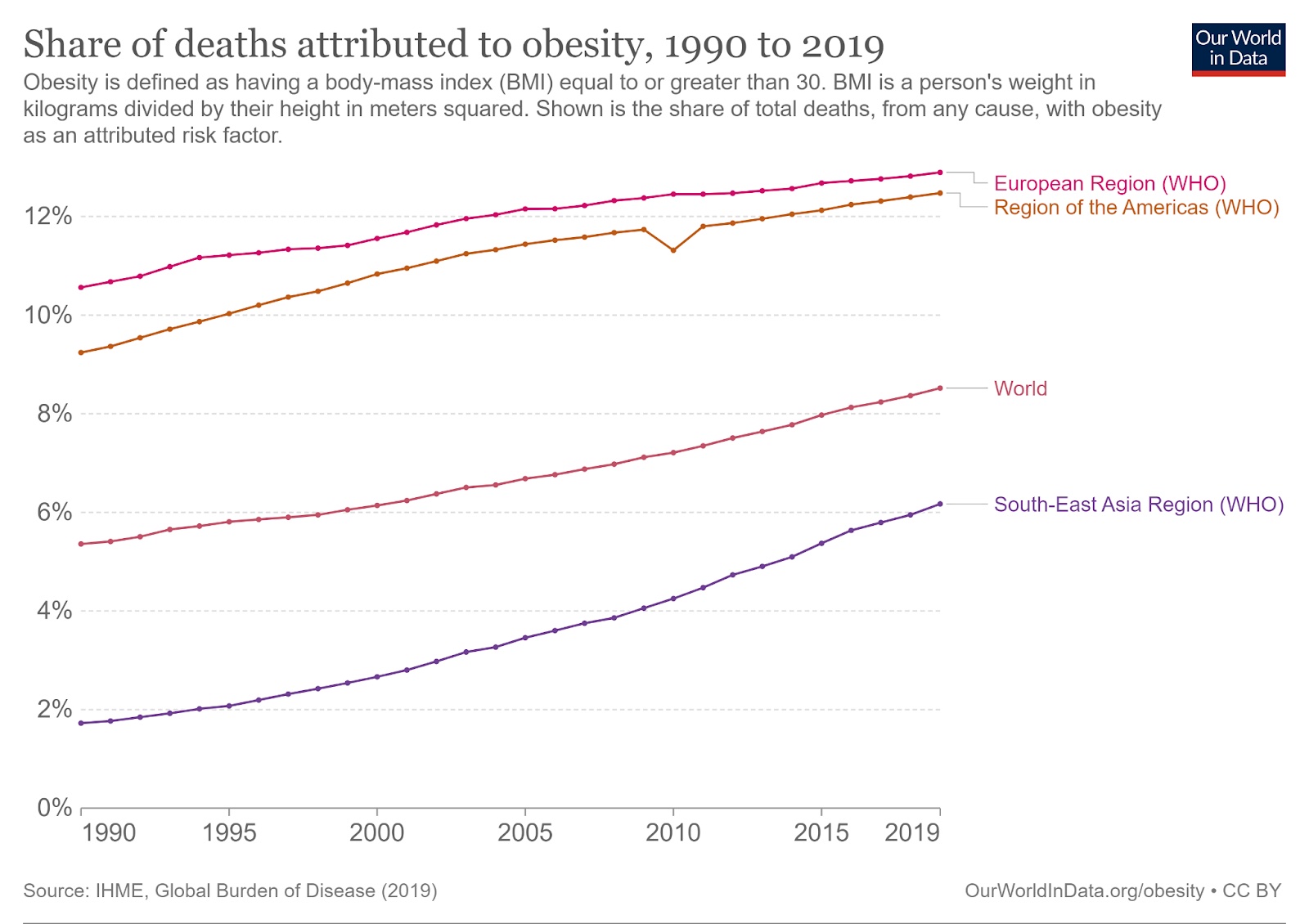

- Globally, obesity is linked to 5 million deaths each year, which is 8.5% of all deaths.

- Emerging treatments for obesity include GLP-1 agonists, brain stimulation, and gene therapy.

This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

The world has a serious weight problem.

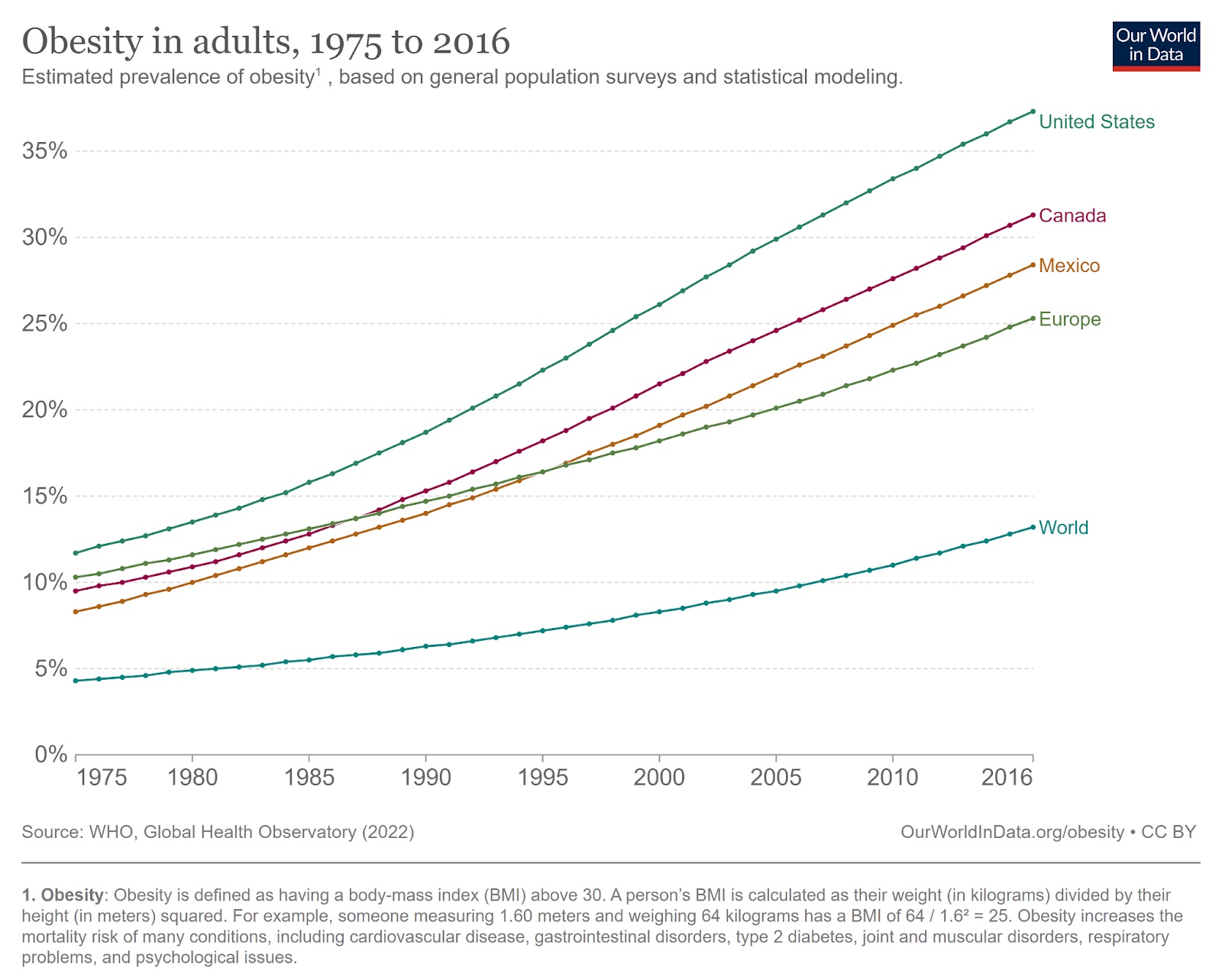

Based on the most common medical standard — body mass index (BMI) — nearly 1 billion people were obese in 2020, and if current trends continue, 1.9 billion people will be obese by 2035. That’s an estimated 24% of the world’s population, with another 27% in the overweight category.

In many countries, like the U.S., the rate is already far higher than that.

This is a huge public health issue.

Obesity increases a person’s risk of many serious health problems, including hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and many cancers. Combined, obesity caused 5 million deaths in 2019 — 8.5% of all deaths and rising.

The stigma associated with obesity can also cause people to experience depression, low self-esteem, and suicidal thoughts, and getting proper medical treatment for any of these issues can be a major challenge — healthcare workers often discriminate against patients who carry significant excess weight.

The traditional prescription for obesity is for people to “simply” eat less and move more. But while this regimen can work, it is easier said than done: losing weight and keeping it off is incredibly hard due to a number of physical, mental, and social factors.

In the past decade, the narrative has started to shift. Now, obesity is being treated more like a disease and less like a moral failing — and as part of that transition, we’re starting to see the development of innovative new obesity treatments to help people lose weight permanently.

GLP-1 agonists

The biggest recent news in the world of obesity treatments has been the development of a class of drugs called “glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1) agonists.” These mimic the activity of the body’s GLP-1 hormone, which is produced after you eat and acts on the brain in a way that suppresses hunger.

GLP-1 agonists were originally developed to treat diabetes — they also lower blood sugar — but doctors noticed that patients on them were also losing a lot of weight, leading to studies of the meds as obesity treatments.

Participants in several big clinical trials dropped a lot of pounds, in the range of 10-20% of their body weight, depending on the particular drug and the dose. People also tend to keep off the weight for as long as they stay on the meds, which are typically delivered as weekly injections (though pill versions are in development).

Semaglutide reduced the risk of heart attacks, strokes, or death from heart disease by 20% in a trial.

There have been reports of rare but serious side effects from GLP-1 drugs, but two are already FDA-approved as obesity treatments — Novo Nordisk’s Wegovy (semaglutide) and Saxenda (liraglutide) — and several are showing promise in clinical trials. Eli Lilly’s drug Mounjaro (tirzepatide) is currently only approved for diabetes, but it is expected to be approved for obesity by the end of 2023.

However, to truly have an impact on obesity in the US, where an estimated 58% of adults will be obese by 2035, GLP-1 agonists need to be more accessible — the drugs currently cost about $1,000 a month and usually aren’t covered by insurance because the companies consider them “lifestyle” drugs and not disease treatments.

That may soon change: Novo Nordisk has announced preliminary results from a trial that has been running since 2017, which found that semaglutide reduced the risk of heart attacks, strokes, or death from heart disease by 20%. If confirmed, this major payoff to overall health could encourage more insurers and Medicare to cover the drug and, potentially, other weight loss prescriptions.

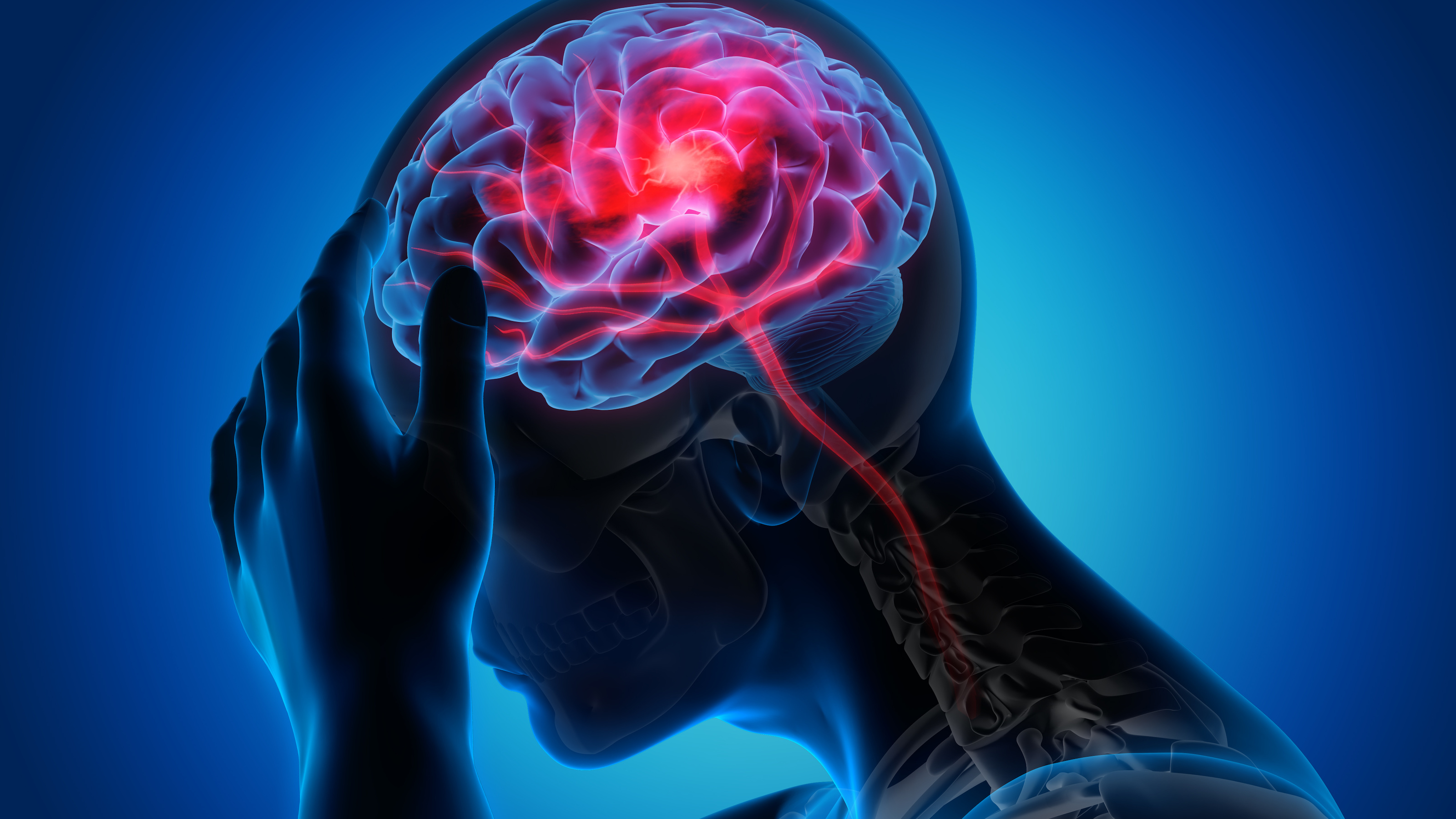

Brain stimulation

Drugs aren’t the only way to stimulate hunger-controlling parts of the brain — electricity can work, too.

In November 2022, researchers at Penn announced that stimulating a part of the brain called the “nucleus accumbens” aided weight loss in two severely obese women with binge eating disorder (BED), a disorder characterized by episodes of rapidly eating a lot of food while feeling a loss of control.

In-development techniques could make brain stimulation a more accessible obesity treatment.

While BED itself isn’t as common as obesity, 70% of people with the disorder are obese, and the study demonstrates how identifying and stimulating the right parts of the brain can help people limit their food intake.

In terms of treating obesity, a team from Allegheny Health Network thinks it might know what the “right” part is, too.

In 2021, they launched a small trial to stimulate an area called the “lateral hypothalamus” in the hope it will help regulate hunger in people with obesity. Those results are expected in 2025.

While both the AHN and Penn treatments require patients to undergo invasive electrode implantation surgeries, researchers are developing less-invasive methods for stimulating regions in the brain, which could make these kinds of treatments more accessible and less risky in the future.

Gene therapy

Because people can be genetically predisposed to obesity, some researchers are targeting these genes.

In 2021, scientists at the University of Massachusetts used CRISPR to knock out a gene called Nrip1 in a type of stem cell found in fat. The gene-edited cells then took on more characteristics of brown fat cells, which help burn calories, rather than white fat cells, which simply store fat. Obese mice that received transplants of the CRISPR’d cells gained less weight than controls when fed a high-fat diet.

If proven safe, gene therapies could be one-and-done obesity treatments.

In May 2023, a team in Spain announced that they’d actually triggered weight loss in obese mice by genetically engineering stem cells extracted from the rodents’ fat tissue to express a protein involved in metabolism. When those gene-edited cells were implanted back into the mice, they enhanced the animals’ ability to burn fat.

Both therapies are in the early stages of development, and because gene therapies are typically irreversible, they’ll likely need to undergo a lot of testing before they’re trialed in people. Still, if successful, they could be one-and-done alternatives to weekly injections of GLP-1 agonists.

The big picture

These are just a few of the many innovative obesity treatments in development.

Other teams are hunting for drugs that mimic the effects of exercise, experimenting with light to trigger feelings of fullness in the stomach, and even exploring the use of psychedelic drugs to promote weight loss.

Still others are working to develop better versions of existing treatments, like bariatric surgery.

Because obesity is a complex disease, with many causes that aren’t entirely understood and lots of variability between individuals, we’re likely going to need this wide variety of treatments to manage it. But developing new treatments isn’t enough.

We also need to ensure that, unlike GLP-1 agonists in the U.S. today, therapies are accessible to everyone who needs to shed weight and keep it off. At the same time, we must continue to reshape the narrative surrounding obesity to ensure those battling it aren’t also bearing the weight of discrimination.

This article was originally published by our sister site, Freethink.