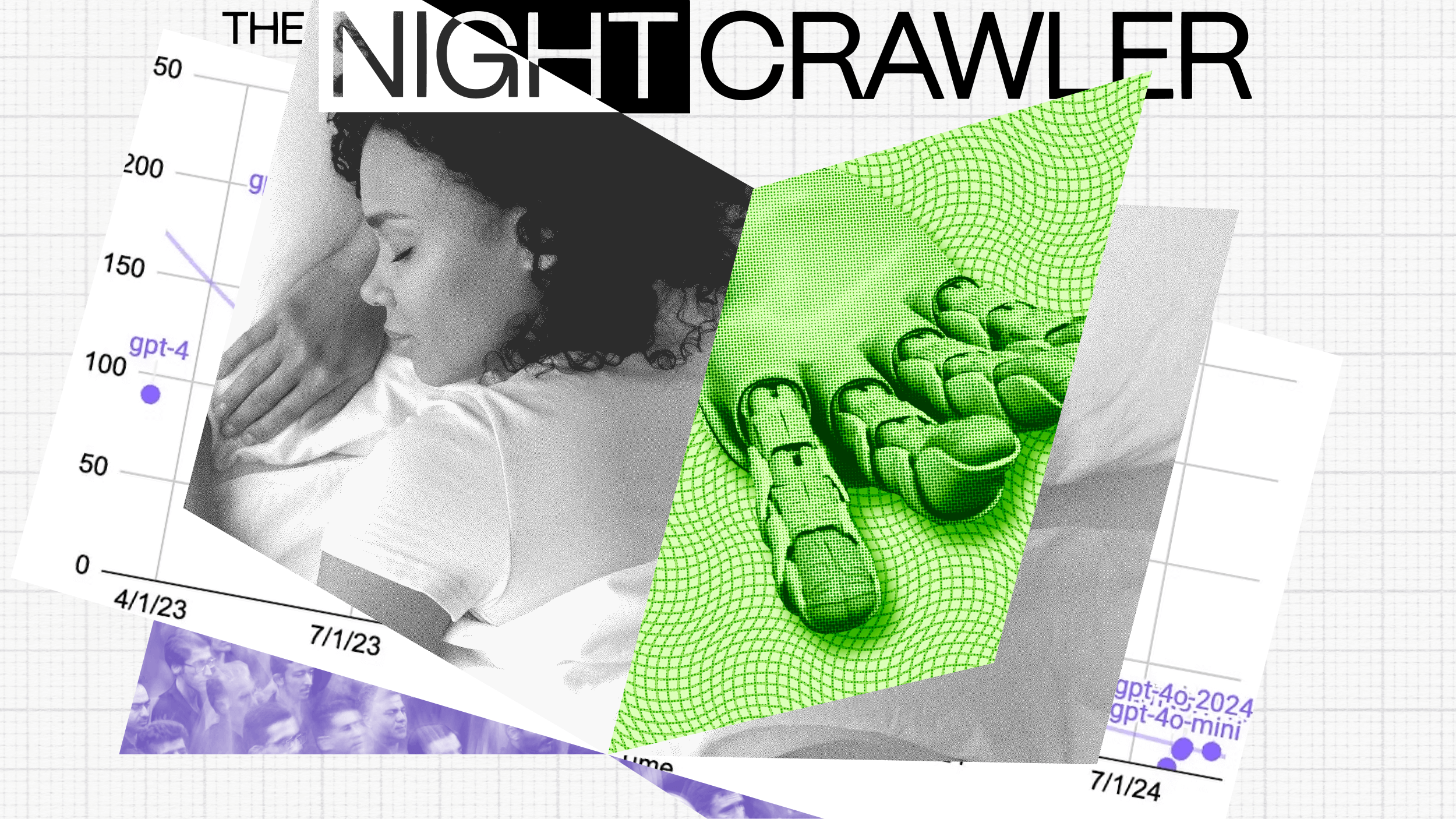

Naps cannot fix sleep deprivation

Credit: Adrian Swancar/Unsplash

- A lack of sufficient slow-wave sleep reduces cognitive ability.

- While naps can help slightly, the effect is so minor as not to be meaningful, according to a new study.

- The study specifically tested participants’ attentiveness and their ability to perform tasks in a prescribed order.

There has been a lot of research into the topic of human sleep, much of it contradictory. Here at Big Think, we have written about research documenting the benefits of naps instead of prolonged sleep, the necessity of 6-8 hours of sleep each night, and how humans only recently began getting that much shuteye, so maybe we don’t need it.

Today, we add more to the canon. Research from Michigan State University finds that naps do not restore cognitive function if you are not getting 6-8 hours of uninterrupted, slow-wave sleep. (This contradicts another Big Think article, of course.) It is one of the first studies to measure the cognitive benefits — or lack thereof — of short naps.

Let’s sleep on it

Slow-wave sleep (SWS) is the most restorative sleep phase. It is the deepest type of non-REM sleep. It is a time when your muscles, heart rate, and respiratory rate are at their most relaxed, and it is characterized by high-amplitude delta brain waves. SWS is associated with memory consolidation, and this is the phase of sleep in which dreams and sleepwalking can occur.

“SWS is the most important stage of sleep,” says Kimberly Fenn of MSU’s Sleep and Learning Lab, an author of the study. “When someone goes without sleep for a period of time, even just during the day, they build up a need for sleep; in particular, they build up a need for SWS. When individuals go to sleep each night, they will soon enter into SWS and spend a substantial amount of time in this stage.”

The authors of the MSU study looked at the effect of sleep deprivation on two types of cognitive tasks: (1) Vigilant attention (the most widely studied metric in sleep-deprivation cognitive research, which refers to the ability to pay attention consistently over time); and (2) placekeeping (the ability to perform a series of steps in a specific order without leaving steps out or repeating any).

A nap is better than nothing

The researchers gathered 275 college-aged recruits at the Sleep and Learning Center. Each participant took a Psychomotor Vigilance Task (PVT) and an UNRAVEL test to measure their baseline attention and placekeeping capabilities, respectively.

Then, the individuals were divided at random into three groups. One group was sent home to get a full night’s sleep. Two other groups stayed at the lab. One was given the option of taking 30- or 60-minute SWS naps over the course of the night. Those in the other group pulled all-nighters. The next morning, the participants took another round of PVT and UNRAVEL tests.

Not surprisingly, those who slept through the night performed better than the other two groups. Fenn reports, “The group that stayed overnight and took short naps still suffered from the effects of sleep deprivation and made significantly more errors on the tasks than their counterparts who went home and obtained a full night of sleep.”

Those who took naps did do a little better than their completely sleepless compatriots. For every additional 10 minutes of SWS sleep, there was a 4% reduction in errors for both types of task. While that small percentage of improvement could make a difference in situations where mental focus and clarity are critically important, the members of this group still never approached the test scores of well-rested participants.

Fenn concludes, “While short naps didn’t show measurable effects on relieving the effects of sleep deprivation, we found that the amount of slow-wave sleep that participants obtained during the nap was related to reduced impairments associated with sleep deprivation.”