Animal magnetism: Bacteria may help creatures sense Earth’s magnetic fields

Credit: PedroNevesDesign/designer_an/Shutterstock/Big Think

- Some animals can navigate via magnetism, though scientists aren’t sure how.

- Research shows that some of these animals contain magnetotactic bacteria.

- These bacteria align themselves along the magnetic field’s grid lines.

It’s one of the more fascinating discoveries of the last several decades: the growing list of animals who can navigate the Earth’s magnetic grid to get where they need to go. From birds to dogs, from fruit flies to lobsters, a number of species are somehow hooked into the planet’s magnetic field — maybe even humans. The big unanswered question is how?

A new paper just published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B may have the answer: The creatures may have a symbiotic relationship with magnetotactic bacteria that orient them along global magnetic field lines.

While it’s possible that the bacteria themselves are just one more magnetically sensitive organism, the paper presents evidence supporting the theory that their presence within other organisms endows their hosts with their magnetic navigational abilities.

A right whale mother and calfCredit: wildestanimal/Shutterstock

One of the paper’s authors, Geneticist Robert Fitak, is affiliated with the biology department of the University of Central Florida in (UCF) Orlando. Prior to joining the department, he spent four years as a postdoctoral researcher at Duke University investigating the genomic mechanisms responsible for magnetic perception in fish and lobsters.

Fitak tells UFC Today, “The search for a mechanism has been proposed as one of the last major frontiers in sensory biology and described as if we are ‘searching for a needle in a needle stack.'”

That metaphorical needle stack may well be the scientific community’s largest database of microbes, the Metagenomic Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology database. It lists the animal samples in which magnetotactic bacteria have been found.

The primary use of the database, says Fitak, has been the measurement of bacterial diversity in entire phyla. An accounting of the appearance of magnetotactic bacteria in individual species is something that has previously be unexplored. “The presence of these magnetotactic bacteria had been largely overlooked, or ‘lost in the mud’ amongst the massive scale of these datasets,” he reports.

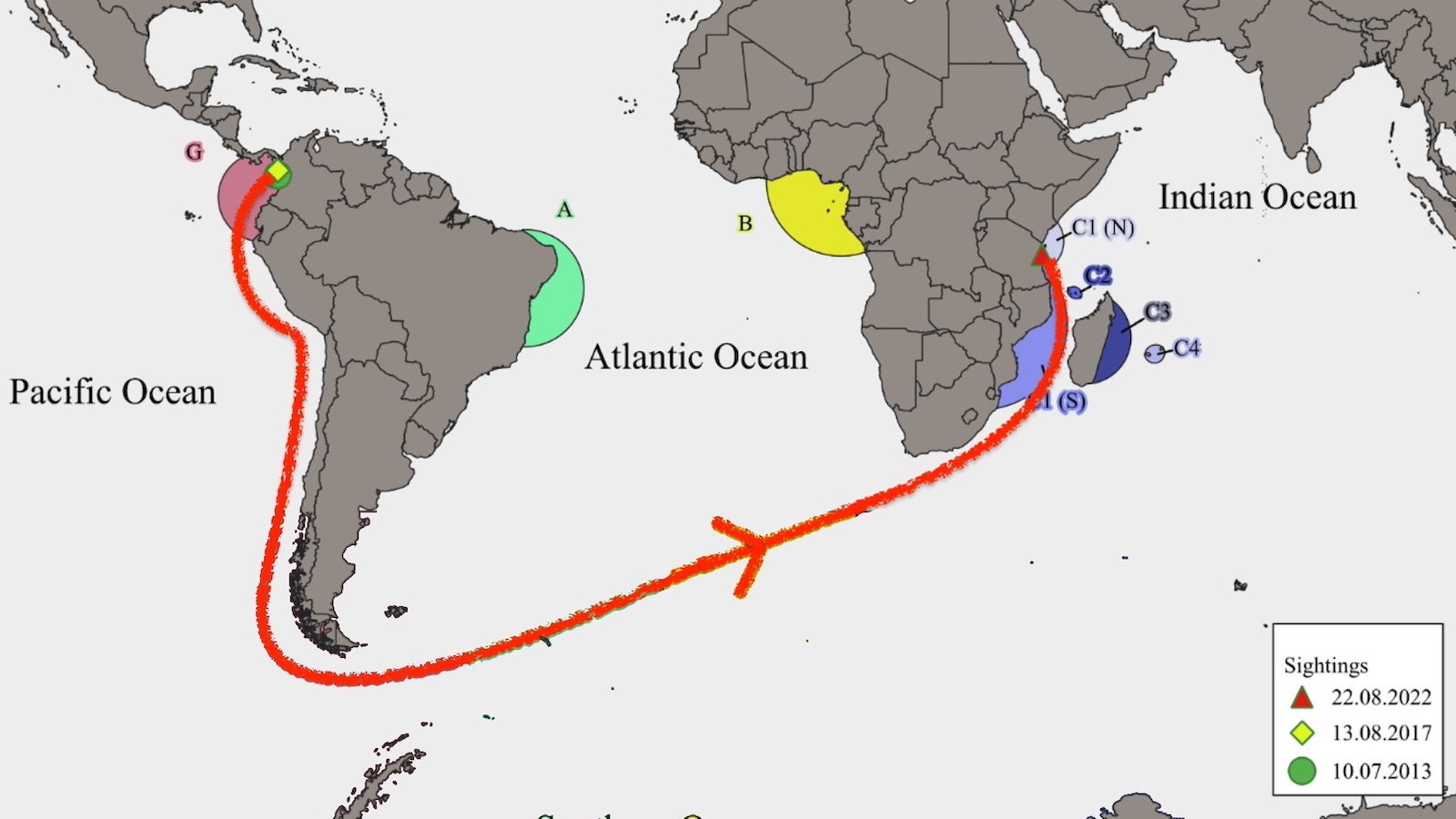

Fitak dug into the database and discovered that magnetotactic bacteria have indeed been identified in a number of species known to navigate by magnetism, among them loggerhead sea turtles, Atlantic right whales, bats, and penguins. Candidatus Magnetobacterium bavaricum is regularly found in loggerheads and penguins, while Magnetospirillum and Magnetococcus are common among right whales and bats.

As for other magnetic-field-sensitive animals, he says, “I’m working with the co-authors and local UCF researchers to develop a genetic test for these bacteria, and we plan to subsequently screen various animals and specific tissues, such as in sea turtles, fish, spiny lobsters and birds.”

While the presence of the bacteria in these particular species is intriguing, further study is needed to be sure they’re responsible for other animals’ magnetic navigation. Their presence in these species could be just a coincidence.

Fitak also notes that he doesn’t know at this point exactly where in the host animal the magnetotactic bacteria would reside, or other details of their symbiotic relationship. He suggests that they might be found in nervous tissue associated with navigation, such as that found in the brain or eye.

If confirmed, Fitak’s hypothesis could suggest that our own sensitivity to the Earth’s magnetic field might one day be enhanced via magnetotactic bacteria in our own individual microbiomes, should they be benign to us as hosts.