- A new study suggests that goosebumps are part of a larger system that not only keeps us warm, but also helps hair to heal.

- The sympathetic nerve system reacts to cold air with goose skin. If it stays on long enough, it orders new hair growth.

- The authors note that other, currently unknown, connections between this system and other parts of the body are likely to exist.

Everybody gets goosebumps, but have you ever wondered why? Until now, the leading hypothesis was that by elevating hair-follicles on the skin, goosebumps helped keep the body warm by providing more space for warm air to be collect near the body. However, many scientists have puzzled over this explanation, as the lack of body hair on modern humans leaves us with the ability to have goose skin but without the ability to benefit from it.

Evolutionarily, that makes little sense, if it really was that useless we’d expect more than a few people to not have the ability to get them by now.

A new study published in Cell suggests a different reason for this reaction. Its authors argue that the same cells that cause goosebumps might be responsible for helping hair growth in the first place, giving a reason for evolution to retain this familiar phenomenon.

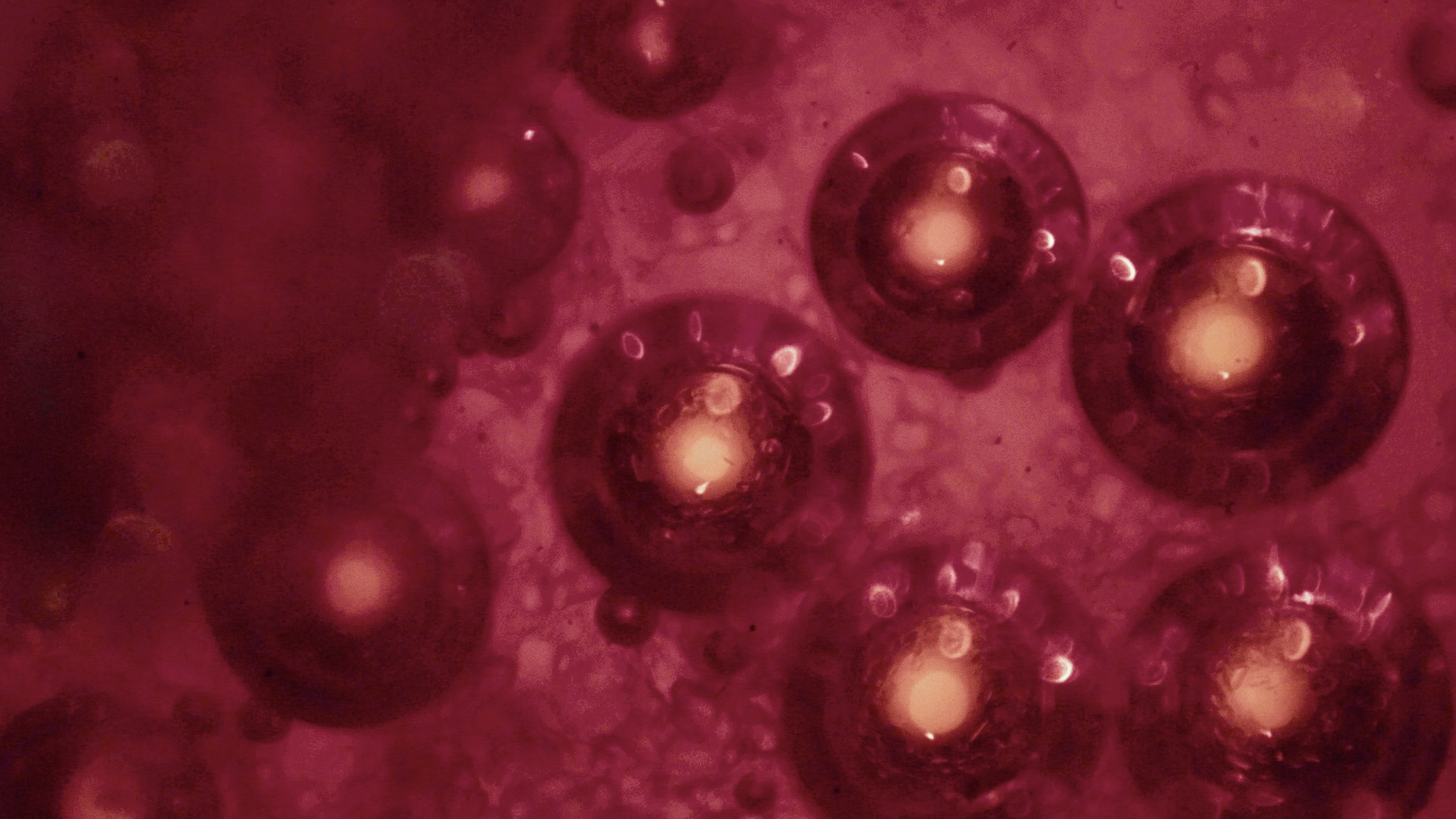

In animals, many organs are made of three kinds of tissue: epithelium, mesenchyme, and nerve. In the skin, which is an organ, a nerve connects to muscle in the mesenchyme. This nerve is part of the sympathetic nervous system and helps maintain homeostasis. The muscle itself is connected to stem cells in the epithelium that heal wounds and regenerate hair follicles.

The researchers focused on mice, as is typical in these studies, but suggest that the findings are also applicable to humans given the similarity between our skin and hair cells.

The researchers examined the behavior and structure of the nerve under an electron microscope. To their surprise, the nerve was not only attached to the previously mentioned muscle tissue but also wrapped around hair follicle stem cells.

In normal conditions, the sympathetic nervous system is always operating at a low level. This keeps the body functioning normally. When the researchers observed this behavior, they noticed signals being sent by the nervous system to the stem cells in the hair follicles. These signals seem to keep the stem cells at the ready for potential use.

However, when the researchers exposed the tissues to the cold, the activity ramped up. A flood of neurotransmitters was released, and the stem cells activated. This prompted new hair growth to begin.

Another experiment dove into how the nerve reached the stem cells in the first place. Co-Author Yulia Shwartz explained the findings in a press release:

“We discovered that the signal comes from the developing hair follicle itself. It secretes a protein that regulates the formation of the smooth muscle, which then attracts the sympathetic nerve. Then in the adult, the interaction turns around, with the nerve and muscle together regulating the hair follicle stem cells to regenerate the new hair follicle. It’s closing the whole circle — the developing hair follicle is establishing its own niche.”

Putting this together, it appears that goosebumps are part of a two-phased response to cold. In the first, the muscle below the skin is stimulated to form goosebumps. If this stimulation lasts long enough, the second phase kicks in, with the sympathetic nervous system calling for new hair growth and repairs for the old ones to be made in response to the cold.

Why I wear my life on my skin

In their press release, the authors suggest that further research can focus on how the body repairs itself in response to environmental stimuli in various situations. The findings also imply that other currently unsuspected connections between the sympathetic nervous system and other parts of the body exist. These potential interactions will undoubtedly be searched for and examined.

Everybody gets goosebumps now and then. We’ve always assumed we knew why we still get them, even though the hypothesis had some holes. This study’s findings show that the benefits of getting goosebumps are more complex than initially thought. It just goes to remind us that we still have much to learn about even the most mundane things.