Fish Skin Bandages: The Latest Product of Medical Desperation

Tucked away in northeast Brazil’s seaside city of Fortaleza, an unusual medical advancement has been discovered. As reported by STAT, researchers and physicians based out of the region’s burn center, the José Frota Institute, have begun testing the use of fish skin as dressings for patients suffering from second- and third-degree burns.

Throughout history, we’ve seen that windows of acute desperation have produced some of the most remarkable medical breakthroughs. The physically grievous casualties generated during World War II forced advancements in the purification, stabilization, and mass production of penicillin. During the height of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, researchers turned to a former cancer drug, AZT, to successfully treat the decade’s most fearsome disease.

Today, Brazil’s medical community faces a uniquely desperate situation. The country’s three operational skin banks are only able to meet approximately one percent of the nation’s needs. Moreover, alternatives to human skin, such as pig skin and synthetic skin substitutes—materials commonly available in the United States—are virtually unobtainable.

Unlike their American counterparts, material and supply shortages have forced some Brazilian burn centers to deviate from the standard medical practice which advocates for early skin grafts, instead being relegated to using traditional gauze-and-silver sulfadiazine cream dressings. While such a method of treatment is time-tested and effective in preventing infection in burn wounds, the dressings necessitate daily and excruciatingly painful changes, which can delay recovery.

Enter fish skin—namely that of tilapia. What was once simply thrown in the trash after harvesting has now become a critical therapeutic agent. After undergoing a thorough cleaning process, the sterilized tilapia skins are applied directly to the wound. For superficial second-degree burns, the skins are left in place until the burn naturally scars over, more severe burns with deeper wound cavities require a few changes over the course of several weeks. While the testing of this technique has been somewhat limited, the consensus amongst attending physicians is that the use of tilapia skin bandages reduces healing time and significantly decreases pain levels in patients.

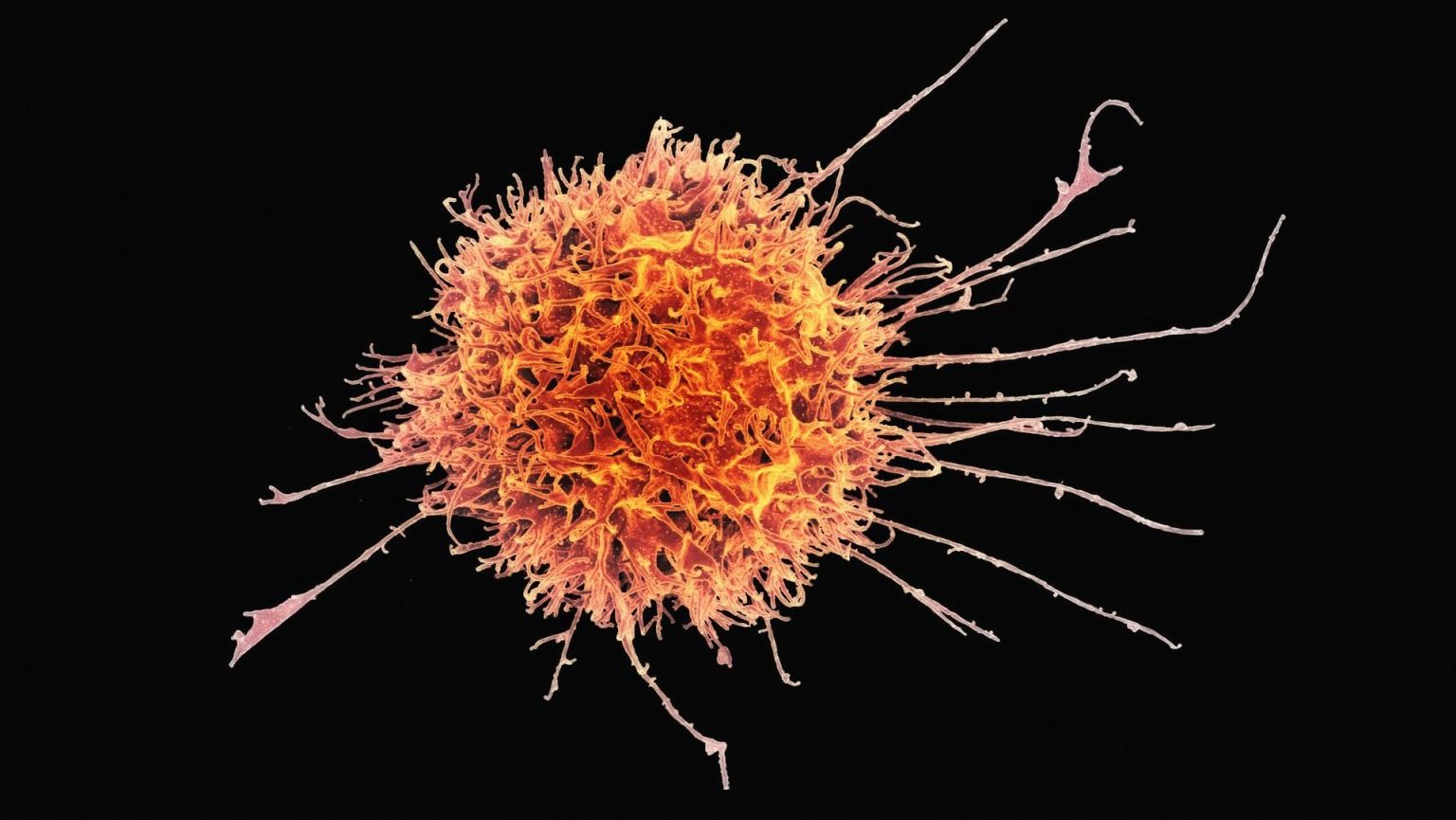

The project’s lead plastic surgeon, Dr. Edmar Maciel, commented on the unexpected superior healing properties of tilapia skin, stating, “We got a great surprise when we saw that the amount of collagen proteins, types 1 and 3, which are very important for scarring, exist in large quantities in tilapia skin, even more than in human skin and other skins. Another factor we discovered is that the amount of tension, of resistance in tilapia skin is much greater than in human skin. Also the amount of moisture.”

Video produced by Nadia Sussman for STAT.

While experts argue that we’re unlikely to see such fish skin bandages in American hospitals, they may very well revolutionize burn care in the medical resource-depleted developing world, where desperation warmly embraces unorthodoxy.

This trend doesn’t end with tilapia skin. In recent years, resource-barren medical professionals have reached back centuries and even millennia in order to find solutions to the mounting challenges posed by the modern age.

Researchers in Nottingham have replicated a Medieval eye salve that has proven capable of destroying 90 percent of antibiotic-resistant MRSA bacteria. Honey, whose medicinal value was held in high regard in antiquity, has recently been heralded by contemporary scientists for its now-proven antimicrobial properties.

Most of us would laugh off notions of leech therapy providing any true medical benefit, yet leech therapy has been firmly incorporated into cosmetic and microsurgery practices for some time now, with the FDA approving its medicinal use in 2004. Moreover, scientists are working diligently to harness the anticoagulant properties of leech saliva for use in the treatment of cardiovascular disease. In another surprising throwback to an ancient era, maggot debridement therapy has been found to be effective in the treatment of diabetes-associated wounds, those often prone to the development of gangrene.

The past has always been an inspiration for the future. We may not see fish skin bandages in US hospitals, but we’ve already—even if quietly—increasingly incorporated the use of other “low-tech” medical treatments in desperate situations. Striding forward with cutting-edge medical advancements has been one of our era’s crowning glories, but making technologies equally accessible throughout the world is the step that’s been missed—hopefully that changes. Until then, necessity will breed invention.