How patients draw their illnesses tells the story of their health outcomes

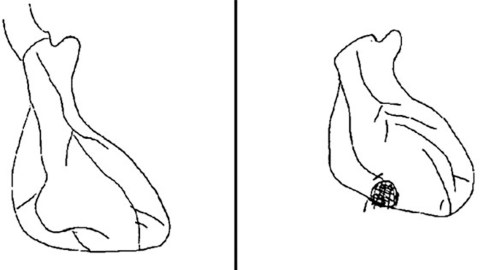

An example of an adult's drawing of the damage and blockages to their heart after a heart attack. (Image: Broadbent et al., 2018)

- One important, but often neglected, factor in the transition from sickness to health is in how patients perceive and understand their illness.

- It’s challenging for physicians to gain insight into the mental and physical state of their patients.

- A new review of 101 articles has found that asking patients to draw their illnesses can help predict health outcomes and provide doctors insight into their patients’ experiences.

One of the challenges to making sick people healthy is to make sure they understand and perceive their illness accurately and stick to treatment plans. Medical researchers have long tried to understand what it takes to get people to follow through on their treatment. Through their research, they developed the Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation. The model really is just common sense, but medical researchers need a name for everything, it seems: The way that patients pursue their goal to get healthy is based on how they perceive their illness.

So, to make sure that patients follow their treatment plans and engage in healthy practices, it’s essential to make sure they understand their illness. There are a variety of ways to figure out whether a patient understands their condition accurately — one would think that it’d be common sense to just ask a patient to describe their illness or maybe fill out a questionnaire. But these methods can influence a patient’s perceptions of their illness, and, as per the Common-Sense Model, influence how they try to get healthy.

Now, a new article published in the January installment of Healthy Psychology Review has taken a deep dive into a growing field of research to try and see how well drawings of an illness correspond to how patients think of their illness, how they’ll cope, and ultimately how likely they are to get healthy again.

Using drawings to predict health outcomes

The idea that drawing an illness can offer insights into a patient’s state of mind and health outcomes is gaining more and more traction in the medical community. Starting from 1970 to 2002, an average of 0.5 papers on this topic were published per year. After that point and up until 2013, an average of 5.9 papers were published on this topic per year.

These papers were the focus of Elizabeth Broadbent and colleagues’ research. “Drawings provide some advantages and disadvantages compared to questionnaire assessments,” they wrote. “[The] advantages include more open responses, the ability of even young children to draw, and the ability to see a reflection of the patient’s perspective in a visual sense.”

So, do drawings correspond to health at all? Their research says yes.

“[A]n adult’s perceptions of control through reduced protein in the kidneys after treatment for lupus compared to before.”

Source: Daleboudt, Broadbent, Berger & Kaptein, Lupus, 20, 290–298.

What drawings can tell us

In the 101 research papers Broadbent and colleagues looked at, they found surprising correlations between different aspects of patients’ drawings and their health outcomes. For example, heart attack patients who drew hearts with larger areas of damage had greater damage, took longer to return to work, and believed that they had less control and that their recovery would take longer. The authors write:

“For example, the area of damage drawn by patients with myocardial infarction was associated with perceived recovery timeline, perceived control, medical indicators of damage, and time to return to work (Broadbent et al., 2004). In a similar study, drawn heart damage was associated with consequences, illness concern, emotional representations, and posttraumatic stress three months later (Princip et al., 2015). In patients with heart failure, drawing heart damage was associated with depression and poor physical functioning (Reynolds, Broadbent, Ellis, Gamble, & Petrie, 2007).”

A similar effect was seen in patients with traumatic brain injury. When they drew their brains, more damaged areas in the drawing were associated with greater consequences from their condition (i.e., impacts on their life), a worse quality of life, more symptoms, a longer recovery time, and other variables.

One interesting repeat finding was that, in general, the larger the drawing size, the more preoccupied patients were with their conditions. Kidney transplant patients, heart failure patients, and heart attack patients who drew larger pictures were more anxious about their condition. More generally, bigger drawings meant the patient perceived their condition as being more serious, and, in turn, bigger drawings were associated with worse health outcomes.

Other drawing characteristics other than size were associated with health outcomes and perception as well. Interestingly, healthy children tended to draw more people in scenes than sick children, who tended to draw more medical instruments and hospital settings. Healthy children also used more color, while sick ones used much less detail in their drawings. In addition, depressed patients tended to use less color, less detail, and more emptiness in their drawings.

“[L]ost occupations as a consequence of pain drawn by an adult.”

Source: Henare, Hocking, & Smyth, British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66.

Why this matters

It’s always difficult for medical experts to know how their patients are feeling physically and emotionally. Since the way illnesses are perceived affect the way that patients go about their recovery, gaining this kind of understanding is crucial. This research demonstrates that drawing exercises can provide insights into a wide variety of perceptions and sensations when it comes to illnesses.

Unfortunately, the corpus of research that Broadbent examined was quite inconsistent; some physicians asked their patients to draw whatever came to mind, others asked them to draw the affected organs, and still others had some different kind of exercise. This made a meta-analysis of the results impossible, which, in turn, obscured the strength of the correlation between the drawings and health outcomes and perceptions.

Nevertheless, to address this inconsistency, and zero in on possible benefits, Broadbent recommend that in future studies researchers use more specific drawing instructions. At the very least, incorporating drawings into treatment plans can enable physicians to point out misconceptions about diseases, but Broadbent and colleagues’ research suggest that this practice may have even more value than that: patients who draw their illnesses might give physicians insight into their perceptions, emotions, and, ultimately, their health outcomes.