Denmark to kill 17 million mink to prevent spread of mutated coronavirus

Credit: Ryzhkov Sergey

- Danish officials say farm-raised mink have infected 12 people with a mutated strain of coronavirus.

- Although those people didn’t suffer especially serious symptoms, they responded relatively poorly to antibody treatments.

- Unlike most other animals, mustelids (like mink) are especially susceptible to contracting coronaviruses.

The Danish government plans to kill millions of farm-raised mink over concerns that the animals are transmitting a mutated form of the novel coronavirus to humans.

In May, Danish officials first announced that mink had likely transmitted the coronavirus to a human working on a farm. Denmark, which is home to about 17 million mink and is the world’s largest producer of mink fur, has since slaughtered more than 1 million mink, while farms in Utah and Spain have killed thousands.

Scientists don’t fully understand how the coronavirus interacts with mink, but early research suggests that mustelids, the family to which mink belong, are more susceptible to the virus. Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen said it’s necessary to cull all mink in Denmark because the virus seems to be mutating within mink populations, and mutated strains could compromise future vaccination efforts.

“…the virus is mutated in mink,” Frederiksen wrote on Facebook. “The mutated virus has spread to humans. And the State Serum Institute has found examples of viruses in people showing reduced susceptibility to antibodies.”

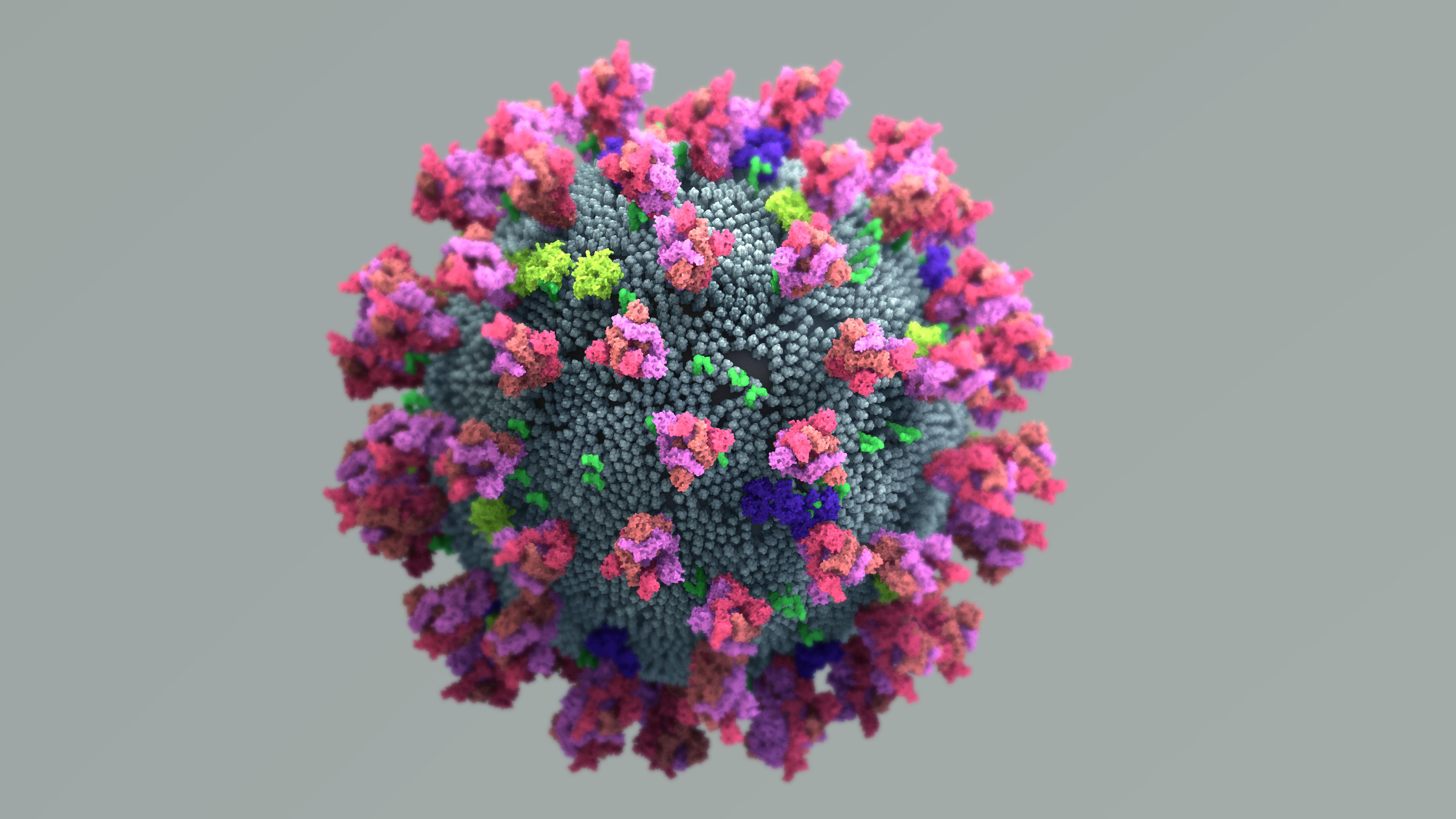

Danish officials said mink have infected at least 12 people (and possibly hundreds more) with the mutated coronavirus, which shows changes to its spike protein. But it’s worth noting that there are no publicly available data for other scientists to examine yet.

What’s more, it’s perfectly normal for viruses to mutate: All viruses are constantly changing, and mutations don’t necessarily make a virus more transmissible or deadly. The Danish patients who reportedly contracted the mutated coronavirus, for example, haven’t suffered especially severe symptoms.

Twittertwitter.com

Still, certain mutations could potentially alter the efficacy of vaccines.

“The worst-case scenario is that we would start off a new pandemic in Denmark,” Kåre Mølbak, the director of infectious diseases at Denmark’s State Serum Institute (SSI), told The Guardian. “There’s a risk that this mutated virus is so different from the others that we’d have to put new things in a vaccine and therefore [the mutation] would slam us all in the whole world back to the start.”

Some researchers said the public shouldn’t panic about the mutations in mink populations.

Twittertwitter.com

Ian Jones, a professor of virology at the University of Reading, noted the lack of publicly available data.

“There does not appear to be any report or data on this mutation in the public domain, so it is hard to comment on the specifics of this story,” he said in a statement. “But the idea that the virus mutates in a new species is not surprising as it must adapt to be able to use Mink receptors to enter cells and so will modify the spike protein to enable this to happen efficiently. The danger is that the mutated virus could then spread back into man and evade any vaccine response which would have been designed to the original, non-mutated version of the spike protein, and not the Mink adapted version.”

Since the pandemic began, scientists have been working to understand how — or whether — the coronavirus spreads from humans to animals, and potentially back to humans. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that while COVID-19 has been found in some animals like cats, dogs and a zoo tiger, there’s currently “no evidence that animals play a significant role in spreading the virus that causes COVID-19.”

That might seem strange. After all, the coronavirus almost surely originated in animals, likely bats. The virus then likely passed from bats to an intermediary host (maybe a pangolin) and then to humans.

In the animal kingdom, there are millions of viruses (many uncatalogued) spreading throughout various species. But the vast majority will never spill over into humans. And among the rare ones that do, most won’t be anywhere near as destructive as the novel coronavirus.

That’s because viruses have to overcome many hurdles in order to jump from species to species.

For example, the host species (known epidemiologically as a reservoir) needs to be shedding enough of the virus when it comes in close contact with another species, say humans. The virus would also need the right kind of protein to bind to human cells. Finally, it would need to replicate itself without getting detected and eradicated by the immune system.

In short, the stars need to align in order for a spillover event to trigger a pandemic. It’s rare, but it happens sometimes.

The concern with the coronavirus spreading among minks is twofold. First, mink raised on farms are kept in crowded conditions, making it easier for the virus to spread among the animals, and thus to humans, if the virus is successfully spilling over.

Second: As the virus spreads among the mink, it’s likely to mutate. Mutations don’t necessarily make a virus more transmissible or deadly. Of course, that’s theoretically possible. Researchers have already catalogued more than 12,000 mutations in SARS-CoV-2 genomes.

Pixabay

But the coronavirus is actually mutating at a relatively slow rate, and the vast majority of those mutations are unlikely to have an effect on transmission rate, morbidity, or mortality.

Mutations could also hurt the virus, as Emma Hodcroft, a molecular epidemiologist at the University of Basel, told Nature: “It’s much easier to break something than it is to fix it.”

(To be sure, research suggests some mutations might be making the coronavirus slightly more transmissible.)

But it’s also possible that mutations to the coronavirus — even those that don’t significantly change its effects on animals or humans — could increase the diversity among SARS-CoV-2 strains to the point where vaccines become less effective.

Without more data, it’s too early to know whether that’s a realistic threat in Denmark or other countries. But Danish officials chose not to front the risk.